Article

EDUCATION NEEDS TO BE RETOOLED AS WELL

By MICHAEL HARAN

Published: Press Democrat; Friday, April 19, 2013 at 7:31pm

After reading Andy Brennan and Simone Harris’ Close to Home article (A teacher’s perspective on improved learning PD 4/4/13) and Bill Gates article (Here’s a fairer way to evaluate teachers PD 4/5/13) on teacher evaluation neither article addressed the new curriculums that are now being developed by K-12 textbook and eBook publishers and the evolution of K-12 teaching methods.

Under Obama’s Race to the Top states are required to meet three main educational criteria: adoption of rigorous academic achievement standards; a program to focus on turning around low performing schools; and the most contentious provision, an accountability system that would involve using test scores to evaluate teachers and principals.

In 2010, California became one of 45 states to adopt the new Common Core State Standards (CCSS) Initiative to meet these criteria and the transition is now under way. Assessments aligned with the standards are also being developed and are expected to be in place for the 2014-15 school year, replacing the STAR tests. The new standards and skill requirements have been developed with the goal of creating consistency across the country.

The California Legislature in March 2011 suspended the adoption of instructional materials until the 2014–15 school year. This was due partially to budget cuts but also to allow time for publishers to adapt instruction materials to the Common Core State Standards (CCSS).

Just like a good race car mechanic a teacher needs sound methodology and precision tools to be successful. Anyone who studies K-12 education knows that the industry has long needed a makeover. Everything evolves and we are now watching an evolution in teaching structure. Many school districts are experimenting with, if not outright adopting, the progressive teaching/learning model called “Flipping the Classroom.”

In flip teaching, the student first studies the topic by himself, typically using video lessons created by the instructor or those provided by an Open Education Recourse (OER), such as the Khan Academy. In the classroom, the pupil then tries to apply the knowledge by solving problems and doing practical applications. The role of the classroom teacher is then to tutor the student when they become stuck, rather than to impart the initial lesson. This allows time inside the class to be used for additional activities, including use of “differentiated instruction” which is more student specific and “project-based learning” which is the practical application.

In another progressive teaching/learning model North Carolina State University College of Education has developed program which they call the FIZZ concept. With this program students video themselves reciting a lesson. The object is to allow students to revisit the video to evaluate and analyze not only what they have learned but also what their peers have learned. The objective is to give the student “ownership” of the lesson which they call the highest level of learning.

Along with the evolution of teaching methodology the next generation of K-12 instruction materials needs to be written to align to these and other progressive teaching models. The publishers now have an opportunity to incorporate modern learning technology with the four predominate student learning styles which are: Linguistic (“word smart” they learn by writing and reading); Logical-mathematical (“number/reasoning smart) Spatial (“picture smart” they learn from images); Bodily-Kinesthetic (“body smart” they need to be moving to learn). I think “Bodily-Kinesthetic learners are many times misdiagnosed with having ADD.

If you want to increase test scores give teachers curriculum that develops the coveted goals of critical thinking, collaboration and communication in all students. You can’t win the race without the right tools.

Michael Haran is research director for the Institute of Progressive Education and Learning.

BLEND, FLIP, DISRUPT

Hechinger Report 1/14/2014

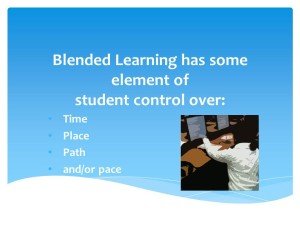

When she introduced Khan Academy videos and quizzes to her sixth-grade math students, Suney Park had to “give up control,” she said at a Blended Learning in K-12 conference at Stanford’s Hoover Institution. “That’s hard.”

But the software lets her students work at their own level and their own pace, moving on only when they’ve mastered a lesson. More are reaching proficiency, says Park, who teaches at Eastside College Prep, a tuition-free private school in all-minority, low-income East Palo Alto, California. “I’ll never go back,” Park said.

Before she tried blended learning, she struggled to “differentiate” instruction for students at very different levels. “You can try it, but you can’t sustain it,” she said. “Teaching to the middle is the only way to survive.” Now, her advanced students aren’t working on a task devised to “keep them out of the way.” They’re moving ahead.

Blended learning is taking off, said Michael Horn, co-founder of the Christensen Institute. It has the potential to “disrupt” the “factory model” of education. If students are practicing skills on their tablets, the teacher can be a small group discussion leader, coach, project organizer, counselor, curriculum planner or . . . who knows? If students are learning at their own pace, should they be organized into “grades” based on age?

However, he warned, “Just because a school is doing blended learning doesn’t mean it’s any good.”

TEACHERS FLIP FOR ‘FLIPPED LEARNING’ CLASS MODEL

By CHRISTINA HOAG, Associated Press | January 27, 2013

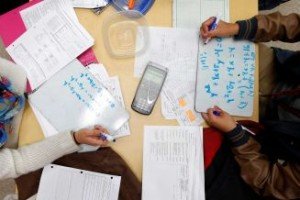

SANTA ANA, Calif. (AP) — When Timmy Nguyen comes to his pre-calculus class, he’s already learned the day’s lesson — he watched it on a short online video prepared by his teacher for homework. So without a lecture to listen to, he and his classmates at Segerstrom Fundamental High School spend class time doing practice problems in small groups, taking quizzes, explaining the concept to other students, reciting equation formulas in a loud chorus, and making their own videos while teacher Crystal Kirch buzzes from desk to desk to help pupils who are having trouble.

It’s a technology-driven teaching method known as “flipped learning” because it flips the time-honored model of classroom lecture and exercises for homework — the lecture becomes homework and class time is for practice. “It was hard to get used to,” said Nguyen, an 11th-grader. “I was like ‘why do I have to watch these videos, this is so dumb.’ But then I stopped complaining and I learned the material quicker. My grade went from a D to an A.”

Flipped learning apparently is catching on in schools across the nation as a younger, more tech-savvy generation of teachers is moving into classrooms. Although the number of “flipped” teachers is hard to ascertain, the online community Flipped Learning Network now has 10,000 members, up from 2,500 a year ago, and training workshops are being held all over the country, said executive director Kari Afstrom.

Under the model, teachers make eight- to 10-minute videos of their lessons using laptops, often simply filming the whiteboard as the teacher makes notations and recording their voice as they explain the concept. The videos are uploaded onto a teacher or school website, or even YouTube, where they can be accessed by students on computers or smartphones as homework. For pupils lacking easy access to the Internet, teachers copy videos onto DVDs or flash drives. Kids with no home device watch the video on school computers.

Class time is then devoted to practical applications of the lesson — often more creative exercises designed to engage students and deepen their understanding. On a recent afternoon, Kirch’s students stood in pairs with one student forming a cone shape with her hands and the other angling an arm so the “cone” was cut into different sections. “It’s a huge transformation,” said Kirch, who has been taking this approach for two years. “It’s a student-focused classroom where the responsibility for learning has flipped from me to the students.”

The concept emerged five years ago when a pair of Colorado high school teachers started videotaping their chemistry classes for absent students. “We found it was really valuable and pushed us to ask what the students needed us for,” said one of the teachers, Aaron Sams, now a consultant who is developing on online education program in Pittsburgh. “They didn’t need us for content dissemination, they needed us to dig deeper.”

He and colleague Jonathan Bergmann began condensing classroom lectures to short videos and assigning them as homework. “The first year, I was able to double the number of labs my students were doing,” Sams said. “That’s every science teacher’s dream.”

In the Detroit suburb of Clinton Township, Clintondale High School Principal Greg Green converted the whole school to flipped learning in the fall of 2011 after years of frustration with high failure rates and discipline problems. Three-quarters of the school’s enrollment of 600 is low-income, minority students. Flipping yielded dramatic results after just a year, including a 33 percent drop in the freshman failure rate and a 66 percent drop in the number of disciplinary incidents from the year before, Green said. Graduation, attendance and test scores all went up. Parent complaints dropped from 200 to seven. Green attributed the improvements to an approach that engages students more in their classes. “Kids want to take an active part in the learning process,” he said. “Now teachers are actually working with kids.”

Students solve problems in Crystal Kirch’s pre-calculus class at Segerstrom High School in Santa Ana, Calif., Wednesday, Jan. 16, 2013. A growing number of teachers are  implementing what is known as “flipped learning,” in which students learn lessons as homework, mostly through online videos produced by teachers,

implementing what is known as “flipped learning,” in which students learn lessons as homework, mostly through online videos produced by teachers,  and use classroom time to practice what they learned. Photo: Jae C. Hong

and use classroom time to practice what they learned. Photo: Jae C. Hong

Although the method has been more popular in high schools, it’s now catching on in elementary schools, said Afstrom of the Flipped Learning Network. Fifth-grade teacher Lisa Highfill in the Pleasanton Unified School District said for a lesson about adding decimals, she made a five-minute, how-to video kids watched at home and in class, then she distributed play money and menus and had kids “ordering” food and tallying the bill and change. A colleague who teaches kindergarten reads a storybook on video. The video contains a pop-up box that requires kids to write something that shows they understood the story.

The concept has its downside. Teachers note that making the videos and coming up with project activities to fill class time is a lot of extra work up front, while some detractors believe it smacks of teachers abandoning their primary responsibility of instructing. “They’re expecting kids to do the learning outside the classroom. There’s not a lot of evidence this works,” said Leonie Haimson, executive director of Class Size Matters, a New York City-based parent advocacy group. “What works is reasonably sized classes with a lot of debate, interaction and discussion.”

Others question whether flipped learning would work as well with low achieving students, who may not be as motivated to watch lessons on their own, but said it was overall a positive model. “It’s forcing the notion of guided practice,” said Cynthia Desrochers, director of the Center for Excellence in Learning and Teaching at California State University-Northridge. “Students can get the easy stuff “on their own,” but the hard stuff should be under the watchful eye of a teacher.”

At Michigan’s Clintondale High School, some teachers show the video at the beginning of class to ensure all kids watch it and that home access is not an issue. In Kirch’s pre-calculus class, students said they liked the concept. “You’re not falling asleep in class,” said senior Monica Resendiz. “You’re constantly working.” Explaining to adults that homework was watching videos was a little harder, though. “My grandma thought I was using it as an excuse to mess around on the Internet,” Nguyen said.

Recent Comments