Articles

NEW ORLEANS CHARTER SCHOOLS SCRAMBLE TO TEACH NON-ENGLISH SPEAKERS

The Hechinger Report 3/23/2014

NEW ORLEANS — Every school night, Ramon Leon helps his older son, a third grader at a New Orleans charter school, with his homework. Typically, they speed through the math worksheets. Word problems take longer because Leon’s son has to translate them into Spanish for his father, who speaks little English. Grammar worksheets sometimes stump them both. (Leon does not want to identify the school to protect his sons’ privacy.)

Leon, who moved to New Orleans from Mexico with his two sons just before the start of the school year, is an involved parent: He attends all report card conferences — using his third grader as an interpreter. On the nights when he can’t help his older son figure out an assignment, he won’t sign the homework form. Instead, he writes “No entiendo” — Spanish for “I don’t understand.”

Usually, the teacher responds with a note to him in English. And the confusion goes on.

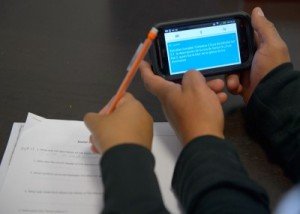

Ramon Leon helps his son, third-grade Ramon Leon Jr., 10, by using the Google Translate app which will scan words from a page and translate them from English into Spanish at the Vietnamese American Young Leaders Association (VAYLA) community office in New Orleans East in New Orleans, La.

Sunday, March 16, 2014. VAYLA community organizer Cristiane Wijngaarde, left, also helps out the Leon family with translation.

(Photo: Matthew Hinton/The New Orleans Advocate)

The Leon family’s dilemma is typical of the challenges facing families that speak Spanish and Vietnamese in New Orleans. Households where the two languages are spoken make up the overwhelming majority of non-English-speakers in New Orleans; and most of their children attend a decentralized school system dominated by independently operated charter schools. Interviews with a dozen families whose children are enrolled in a range of schools found that many charters fail to translate letters, school calendars, or even report card results for parents. Typically, all signs posted in the school’s office are written in English. Automated phone calls to parents are in English.

On-site interpreters are scarce, parents said. One mother described trying, unsuccessfully, to tell the school nurse that her son had been diagnosed with exercise-induced asthma that could be triggered in physical education classes. Students frequently end up interpreting between teachers and parents at report card conferences — and even at meetings where their own discipline problems are being discussed.

As a result of these gaps in services VAYLA partnered with the National Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund last year to file a federal complaint. They did so on behalf of 35 Spanish- or Vietnamese-speaking parents with students at five named schools as well as all other non-English-speaking parents of children throughout the city’s public school system.

The complaint alleged that the Orleans Parish School District and the state-run Recovery School District, both of which oversee charter schools as well as traditional, centrally administered schools, routinely fall short of federally mandated translation services for parents who speak little or no English.

“I have a voice,” Theresa Thao, a parent, said. “It may be in Vietnamese, but it is my voice.”

Specifically, the complaint outlined how most of the schools fail to provide translated documents concerning major school events, parent-teacher conferences, school closures, disciplinary infractions, special education services, and numerous other topics, despite federal law requiring school districts to “communicate as effectively with language-minority parents as (they) would with other parents,” as an explanation published by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights requires.

Barry Landry, a spokesman for the Louisiana Department of Education, said he couldn’t comment on the complaint. He said the state monitors charter schools to ensure their services for non-English speaking families are in compliance with federal mandates, but that most of the monitoring is limited to paperwork reviews.

While many school districts nationwide struggle to serve non-English speaking families adequately, particularly those that have gone through budget cuts, the situation in New Orleans is unique. Between 2000 and 2010, the Latino population in New Orleans increased by 57 percent, drawn largely by hurricane-recovery work. Dozens of independent public charter schools opened in the years after Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005, most with little expertise with or infrastructure for working with families not fluent in English.

“We haven’t seen this kind of situation elsewhere,” said Thomas Mariadason, a lawyer for the legal defense fund. “There’s nothing quite like the education landscape in New Orleans.”

The struggles to serve Spanish and Vietnamese-speaking families in New Orleans are shaped by two different forces. First, the number of non-English speakers has grown rapidly in recent years.

Leon and his son often use a smartphone app to help them translate paperwork or figure out word problems.

(Photo: Matthew Hinton/The New Orleans Advocate)

Nationwide, one in 10 students speak a language other than English. But until recently, New Orleans bucked that trend. Even a decade ago, a sluggish New Orleans economy attracted few new people: U.S. Census data from 2000 showed that nearly 80 percent of the city’s residents were born in Louisiana, the highest rate of native-state residents for any American city.

Most New Orleans public schools had few, if any, non-English speaking students, with the exception of a few schools clustered near a community of Vietnamese refugees in eastern New Orleans, resettled by the local Catholic archdiocese after the end of the Vietnam War.

As New Orleans rebuilt following Hurricane Katrina, it changed. Plentiful construction jobs and a strong economy attracted nearly 5,000 new Hispanic residents, many of whom settled here with their families. The number of students with limited English skills has nearly tripled in New Orleans public schools within recent years: from 440 in 2006 to about 1,200 at the start of this school year, according to data provided by the Louisiana Department of Education.

The second change relates to the decentralization of the schools. The autonomy of charter schools distances them from centralized support structures that might help provide translation services for parents or a greater amount of bilingual education for their children. Many of the schools are now striving to create these services, but without the economies of scale that can be realized by sharing interpreters or bilingual teachers system-wide.

“They’re operating like silos,” said Ofelia García, professor of urban education at the City University of New York, who has edited and authored several books about bilingual and language education.

In 2011, the Louisiana Language Access Coalition, which formed in the wake of Katrina to address unmet language needs of new residents, prompted some systemic reforms when it convinced then-Recovery School District Superintendent John White to place Vietnamese and Spanish interpreters in its school registration centers. At the coalition’s request, White also agreed to provide funding to translate the Parent’s Guide, a directory of New Orleans schools, into the same two languages.

But within a couple of years, as the interpretation service grew erratic, the group felt unable to make headway on anything else, said coalition co-chair Daesy Behrhorst. State education spokesman Barry Landry said that the erratic scheduling was due to a change in staff and that the RSD is now hiring new Vietnamese and Spanish interpreters for the centers, with money recently supplied by the New Orleans City Council.

Language Access Coalition leaders have now realized that to influence policy, they must knock on many doors. This year, coalition members plan to visit the operators for each of the city’s roughly 80 charter schools and the handful of schools still direct-run by Orleans Parish School Board. “To support parents, we have to talk to every school,” said Behrhorst.

Other advocacy organizations have gotten creative in order to help parents get the services they need in a balkanized school landscape.

On any given day, for instance, VAYLA youth advocate Cristi Wijngaarde answers her cell phone several times, only to hear English-only robocalls advising parents about early school closures, mandatory parent meetings, field trips, detention, and undone homework. Several Spanish-speaking parents added Wijngaarde to their school’s call list because they couldn’t understand the messages. Each time a robocall comes through, the parents follow up with Wijngaarde for an explanation.

On a recent evening, Theresa Thao stopped at VAYLA to ask about her ninth grade daughter’s recent sick day, which was marked unexcused. Thao, who speaks some English, said she initially found it very difficult to be pushy. She used to get physically ill when she had to go to a child’s school and complain. And she had to ask an older daughter to take time off from college to interpret at regular meetings about a son’s special education needs, since the documents were not translated.

Staff members at VAYLA have helped her build more confidence and get necessary answers.

In the case of the ninth-grade daughter, who attends KIPP Renaissance High School, Wijngaarde explained that the school office must have lost the doctor’s note and advised Thao to bring a new one and ask for a copy of it.

When Thao visits on her own, she has learned to stay until she is sure her point is understood. At Renaissance, where there’s rarely an interpreter available, she sometimes demands to speak to the principal. (In a statement, a KIPP spokesman said KIPP works with non-English speaking families to develop individual plans that meet their needs.)

“I have a voice,” Thao said. “It may be in Vietnamese, but it is my voice.”

The complications facing educators

Most of the city’s charter schools have programs of some kind for students not fluent in English although they vary considerably in terms of their approach, expertise, and success.

The VAYLA complaint, which was filed with the U.S. Department of Education and the Department of Justice’s Office of Civil Rights, focuses primarily on charter schools’ failures to communicate with parents. Yet at the same time, many of the same schools are struggling to figure out the best way to educate students with limited English skills — whether by hiring more bilingual teachers or providing better training for English-speaking instructors. They sometimes lack the budgetary flexibility to do as much as they would like.

Launching a program for students without strong English skills is complicated partly because standards vary from state to state and there’s still considerable disagreement on the most effective ways to educate these students. Louisiana’s English learner handbook gives very little curriculum guidance except to caution that programs “should not segregate English language learners beyond the extent necessary.”

“It’s not a clear-cut slam-dunk answer,” said Claude Goldenberg, a Stanford University education professor and expert on literacy and non-native speakers. While a strong bilingual program (which involves teaching in both the child’s native language and English) is preferable, not every school has the capacity to create one, he said. So what matters most is a strong academic curriculum with teachers trained to work with students who are not proficient in English. There also should be time set aside each day for specialized English-language instruction, when non-native speakers can concentrate on learning the language, Goldenberg said.

In some ways, New Orleans has it easy because its schools deal primarily with two languages, Wijngaarde says. “We have Spanish and Vietnamese. We don’t have 40 or 50 languages like New York City,” she said. In places like New York, English-as-a-second language (or ESL) teachers become skilled in working with small classes of students who may speak five different native languages but are grouped by their English ability.

A few of New Orleans’ schools, including Einstein charter school in eastern New Orleans, have seasoned ESL teachers and have worked with Vietnamese refugees and their children in the area since the mid-1970s. Einstein is located not far from the thriving Mary Queen of Vietnam Church, which after Katrina began holding masses in both Vietnamese and Spanish.

Einstein has 162 students not fluent in English, more than any other charter school in the city. The school’s robocalls are recorded in three languages — English, Vietnamese, and Spanish. The front office includes a Vietnamese-speaking staff person. Einstein also translates what it considers “important” correspondence, including report card results and special education notices, although the school’s monthly calendar and some other notes are issued in English alone.

Within the school itself, there is an entire row of classrooms for English-language instruction. English learners are pulled out of regular classes for 60-minute blocks where they focus on learning the basics of the language using teaching aids, such as drawings of shapes, colors and common nouns. New arrivals with little, if any, knowledge of English are pulled out for longer blocks.

But even Einstein is experiencing hiccups, particularly as it adapts to an influx of Spanish-speaking families. In the federal complaint, a few Hispanic parents described difficulties communicating with school officials during emergencies — including one case where a student was injured, and another where a child was about to be arrested for alleged vandalism.

Shawn Toranto, the school’s CEO, would not address the specifics of the complaint. But Toranto said the school now has 25 staffers who can speak Vietnamese and four who speak Spanish, including a paraprofessional who can be pulled from classrooms to translate.

Toranto believes Einstein’s growing pains are in the past, and said she welcomes the increase in English learners. “We’ve always had a diverse population. We accept it and know what we need to do,” she said.

Other charter school operators without Einstein’s long history are figuring out how to serve English learners and their families for the first time. Ben Marcovitz, the founder of Collegiate Academies, a network of three charter schools including Sci Academy, noted that communicating with families who speak little English has presented unique challenges. At Sci Academy, for instance, though most of the ELL students are Vietnamese, only one instructor, a paraprofessional, speaks the language, compared with seven who speak Spanish.

English learners started showing up two years ago at all three schools and now make up roughly 4 percent of the overall student body. The network relies heavily on technology to help communicate with families. The front office, for example, uses a three-way telephone language line to interpret for parents and the network gives all English learners personal electronic translators.

Oanh Nguyen, a junior now earning straight As, recalled her first year at the school two years ago, when she depended mostly on her electronic translators and an English-speaking advisor whom she met with every day. “There was no Vietnamese speaker who could help me in class,” she said. “I mostly could not talk. I just kept silent. I could not do much work.”

Now, her English has improved to the point where she is able to translate for her parents at report card conferences. But the school says that won’t be necessary, since Sci Academy has started making interpreters available on report card nights as part of an effort to “radically” bolster services for parents.

Charter networks that run multiple schools often fare better because they have larger numbers of students and more budgetary flexibility. FirstLine, which runs five schools in New Orleans, has been able to phase in a small department designated to serving English learners and their families.

Diana Richard, FirstLine’s English-as-a-second-language coordinator, started the department two years ago, slowly adding more and more services for the families. This school year, FirstLine began recording all robo-calls in English and Spanish. All field trip permission notices are now automatically produced in Spanish as well as English. A bilingual paraprofessional is available to families and teachers every day to translate documents and correspondence into Spanish. And a Loyola University professor and his class translated the school’s longer documents, like the 32-page student handbook, into Spanish. Once a week, the school hosts a story hour after school in both English and Spanish.

If teachers need to communicate with a Spanish-speaking parent, Richard will often call or text for them. But if Richard is busy, the teachers reach out to other bilingual FirstLine colleagues and avoid using students as translators.

It’s that kind of broad support that stand-alone schools often lack. But good intentions still go a long way with parents, said Leon, the father who moved recently from Mexico with his two sons. He held up his phone and played a recent voicemail message from his son’s teacher. The teacher spoke Spanish butchered so badly that no one he knows could understand it.

In Houston, where his nephews go to school, teachers routinely ask Spanish-speaking colleagues to leave messages. But that must not be so easy an option in New Orleans, he said, cranking up the volume to show why the teacher’s speech was so halting. In the background, a young child gave her prompts, word by word, in Spanish.

At least, Leon said, she was trying.

Recent Comments