Articles

K-12 Online For-Profit Schools

MEDIA COMPANIES, SEEING PROFIT SLIP, PUSH INTO EDUCATION

Chris Keane for the New York Times

By Brooks Barnes and Amy Chozick

LOS ANGELES — As another academic year starts, about 500,000 children across the country will find themselves learning subjects like middle school history or high school biology from a new line of digital textbooks. These manuals, branded Techbooks, come with all the Internet frills: video, virtual labs, downloadable content.

Last year, Discovery introduced its line of digital textbooks, called Techbooks. The manuals are used at Mooresville Middle School in North Carolina.

But the Techbook may be most notable for what it does not have — backing from a traditional educational publisher. Instead it has the support of Discovery, the cable TV company. Discovery, which also sells an educational video service to school districts, is entering the digital textbook market largely because it sees a growth opportunity too good to pass up.

company. Discovery, which also sells an educational video service to school districts, is entering the digital textbook market largely because it sees a growth opportunity too good to pass up.

Conventional K-12 textbooks are a $3 billion business in the United States, according to the Association of American Publishers, with an additional $4 billion spent on teacher guides, testing resources and reference materials. And almost all that printed material, educators say, will eventually be replaced by digital versions. “It’s kind of perfect for us,” said David M. Zaslav, chief executive of Discovery Communications, which owns networks like Discovery Channel, Animal Planet and TLC. “Educational content is core to our DNA, and we’re unencumbered — unlike traditional textbook publishers, we’re not defending a dying business.”

Mr. Zaslav is not the only media executive talking grandly about education these days. Movies, television, newspapers and magazines are in decline or facing headwinds, putting pressure on media companies to find new areas of expansion. Education is emerging as an answer, largely because executives see a way to capitalize on the changes that technology is bringing to classrooms — turnabout as fair play, given the way that the Web has upended major media’s own business models. “We think the opportunity continues to be to use digital technologies to be disruptive to an enormous business stuck decades in the past,” Chase Carey, News Corporation’s chief operating officer, told analysts this year.

Mr. Zaslav is not the only media executive talking grandly about education these days. Movies, television, newspapers and magazines are in decline or facing headwinds, putting pressure on media companies to find new areas of expansion. Education is emerging as an answer, largely because executives see a way to capitalize on the changes that technology is bringing to classrooms — turnabout as fair play, given the way that the Web has upended major media’s own business models. “We think the opportunity continues to be to use digital technologies to be disruptive to an enormous business stuck decades in the past,” Chase Carey, News Corporation’s chief operating officer, told analysts this year.

News Corporation is betting on just that. This month, the company said it would infuse its fledgling education division, Amplify, with $100 million. Amplify, focused on digital teaching and assessment tools, is run by Joel I. Klein, the former New York City schools chancellor. Rupert Murdoch, the chief executive of News Corporation, has said he would be “thrilled” if education were to account for 10 percent of its revenue five years from now.

Old-line education companies, however, may be more difficult prey than Mr. Zaslav and Mr. Murdoch think. Pearson, McGraw-Hill and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt are introducing digital educational products of their own, and these stalwarts have a technology giant on their side: Apple, seeking to bolster iPad sales, recently started selling digital high school textbooks through its iBooks store, with those three publishers as partners. “Over the last 10 years alone, we’ve invested $9.3 billion in digital innovations that are transforming education,” said Will Ethridge, chief executive of Pearson North America, part of Pearson P.L.C., the world’s largest education and learning company. “One way to describe it would be an act of ‘creative destruction.’ By this I mean we’re intentionally tearing down an outdated, industrial model of learning and replacing it with more personalized and connected experiences for each student.”

Old-line education companies, however, may be more difficult prey than Mr. Zaslav and Mr. Murdoch think. Pearson, McGraw-Hill and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt are introducing digital educational products of their own, and these stalwarts have a technology giant on their side: Apple, seeking to bolster iPad sales, recently started selling digital high school textbooks through its iBooks store, with those three publishers as partners. “Over the last 10 years alone, we’ve invested $9.3 billion in digital innovations that are transforming education,” said Will Ethridge, chief executive of Pearson North America, part of Pearson P.L.C., the world’s largest education and learning company. “One way to describe it would be an act of ‘creative destruction.’ By this I mean we’re intentionally tearing down an outdated, industrial model of learning and replacing it with more personalized and connected experiences for each student.”

On a smaller scale, NBC Universal has been building a service called NBC Learn, which digitizes and archives video and articles from NBC News to sell as a database and digital blackboard learning system; NBC Learn now operates in 5,000 schools in 43 states.

The Financial Times, owned by Pearson, is pushing MBA Newslines, a subscriber-only feature on its Web site that lets business students and professors create and share annotations on articles, allowing case studies to be built around real-time news events.

The Financial Times, owned by Pearson, is pushing MBA Newslines, a subscriber-only feature on its Web site that lets business students and professors create and share annotations on articles, allowing case studies to be built around real-time news events.

And then there is the Walt Disney Company. It is building a chain of language schools in China big enough to enroll more than 150,000 children annually. The schools, which weave Disney characters into the curriculum, are not going to move the profit needle at a company with $41 billion in annual revenue. But they could play a vital role in creating a consumer base as Disney builds a $4.4 billion theme park and resort in Shanghai.

Media companies have dipped their toes into education before, of course, only to find chilly waters. Discovery in 2006 promoted COSMEO an Internet-based service that offered children videos and other tools to help them with their homework; a year later, Discovery decided to stop marketing the product, which cost $99 a year, and laid off much of its staff. (Why pay for help when you can search Google at no cost?)

Media companies have dipped their toes into education before, of course, only to find chilly waters. Discovery in 2006 promoted COSMEO an Internet-based service that offered children videos and other tools to help them with their homework; a year later, Discovery decided to stop marketing the product, which cost $99 a year, and laid off much of its staff. (Why pay for help when you can search Google at no cost?)

In 2007, Disney introduced a new position — senior vice president for learning — with the goal of moving into the North American education businesses. None of the company’s major efforts got off the ground, and Disney eventually pulled the plug, in part because it decided technology was changing the sector too rapidly.

News Corporation faces perception hurdles as it moves deeper into education — namely what some rivals refer to as the “Foxification” of schools, a pointed reference to Fox News Channel and its stable of conservative pundits. The company has said it has zero interest in inserting politics into schools, and notes that other assets, including the National Geographic Channel, which, like Discovery’s flagship channel, largely focuses on documentaries and educational programming, could play to the company’s advantage.

Last year, the New York State comptroller, citing News Corporation’s phone-hacking scandal in Britain, rejected a $27 million contract with its education division. The decision underscored one of the biggest hurdles faced by companies entering the education market: new products must typically gain state approval before schools even have the chance to decide to buy them.

Last year, the New York State comptroller, citing News Corporation’s phone-hacking scandal in Britain, rejected a $27 million contract with its education division. The decision underscored one of the biggest hurdles faced by companies entering the education market: new products must typically gain state approval before schools even have the chance to decide to buy them.

Wall Street is skeptical that education holds as much promise as some media companies think. “When big conglomerates feel their core businesses have started to mature, they look for related synergistic businesses,” said David Bank, an analyst at RBC Capital Markets. “You have to ask yourself, are those education businesses really related and synergistic in core?”

Bill Goodwyn, chief executive of Discovery’s education unit, says in his company’s case, the answer is an emphatic yes. He conceded that COSMEO “lost a lot of money,” but said that Discovery’s business had centered on education since its earliest days. Discovery Channel’s original name was Cable Education Network, for instance, and the company used to make money by shipping VHS cassettes of documentaries to schools.

Bill Goodwyn, chief executive of Discovery’s education unit, says in his company’s case, the answer is an emphatic yes. He conceded that COSMEO “lost a lot of money,” but said that Discovery’s business had centered on education since its earliest days. Discovery Channel’s original name was Cable Education Network, for instance, and the company used to make money by shipping VHS cassettes of documentaries to schools.

Discovery currently sells a popular subscription streaming service to schools, which comes with 50,500 video segments and 6,200 full-length videos on topics like math, social studies and language arts. The service costs $1,570 a year for a school that serves kindergarten through eighth grade; high schools pay $2,095.

Still, Discovery’s previous efforts pale in scope to its Techbook initiative. Mr. Goodwyn’s 200-employee division introduced the line of digital textbooks last year. Their cloud-based technology works with whatever hardware a district has — iPads, laptops, desktops. Discovery tailors them to the particular curriculum needs of various states (or districts within states).

“As a 30-year veteran, it was not always easy giving up some of the more traditional ways of teaching,” said Roseann Burklow, a seventh-grade science teacher in Mooresville, N.C. “But I love the Techbook. Students are engaged and can work independently or collaboratively.” (She did suggest one improvement: more games to help students review material for tests.)

“As a 30-year veteran, it was not always easy giving up some of the more traditional ways of teaching,” said Roseann Burklow, a seventh-grade science teacher in Mooresville, N.C. “But I love the Techbook. Students are engaged and can work independently or collaboratively.” (She did suggest one improvement: more games to help students review material for tests.)

Traditional textbooks cost about $70 a student; Discovery’s Techbooks start at $38 a student for a six-year subscription and go up to $55, depending on the subject and grade level.

Discovery knows education will never pay its bills. Last year, the company’s learning products, for instance, generated adjusted operating income of $23 million, a 53 percent increase over a year earlier. In comparison, its United States cable networks delivered operating income of $1.5 billion, a 10 percent increase from a year earlier.

Still, Mr. Zaslav said the education unit’s small size did not dim his enthusiasm. “Television is always going to be our primary focus, but we’re incredibly excited about the business potential of the Techbook,” he said. “Education is an area of solid, sustainable growth.”

THE CAMPUS TSUNAMI

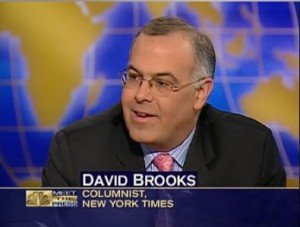

By David Brooks

New York Times – May 3, 2012

Online education is not new. The University of Phoenix started its online degree program in 1989. Four million college students took at least one online class during the fall of 2007.

But, over the past few months, something has changed. The elite, pace-setting universities have embraced the Internet. Not long ago, online courses were interesting experiments. Now online activity is at the core of how these schools envision their futures.

But, over the past few months, something has changed. The elite, pace-setting universities have embraced the Internet. Not long ago, online courses were interesting experiments. Now online activity is at the core of how these schools envision their futures.

This week, Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology committed $60 million to offer free online courses from both universities. Two Stanford professors, Andrew Ng and Daphne Koller, have formed a company, Coursera, which offers interactive courses in the humanities, social sciences, mathematics and engineering. Their partners include Stanford, Michigan, Penn and Princeton. Many other elite universities, including Yale and Carnegie Mellon, are moving aggressively online. President John Hennessy of Stanford summed up the emerging view in an article by Ken Auletta in The New Yorker, “There’s a tsunami coming.”

What happened to the newspaper and magazine business is about to happen to higher education: a rescrambling around the Web. Many of us view the coming change with trepidation. Will online learning diminish the face-to-face community that is the heart of the college experience? Will it elevate functional courses in business and marginalize subjects that are harder to digest in an online format, like philosophy? Will fast online browsing replace deep reading?

If a few star professors can lecture to millions, what happens to the rest of the faculty? Will academic standards be as rigorous? What happens to the students who don’t have enough intrinsic  motivation to stay glued to their laptop hour after hour? How much communication is lost — gesture, mood, eye contact — when you are not actually in a room with a passionate teacher and students?

motivation to stay glued to their laptop hour after hour? How much communication is lost — gesture, mood, eye contact — when you are not actually in a room with a passionate teacher and students?

The doubts are justified, but there are more reasons to feel optimistic. In the first place, online learning will give millions of students’ access to the world’s best teachers. Already, hundreds of thousands of students have taken accounting classes from Norman Nemrow of Brigham Young University, robotics classes from Sebastian Thrun of Stanford and physics from Walter Lewin of M.I.T.

Online learning could extend the influence of American universities around the world. India alone hopes to build tens of thousands of colleges over the next decade. Curricula from American schools could permeate those institutions. Research into online learning suggests that it is roughly as effective as classroom learning. It’s easier to tailor a learning experience to an individual student’s pace and preferences. Online learning seems especially useful in language and remedial education.

The most important and paradoxical fact shaping the future of online learning is this: A brain is not a computer. We are not blank hard drives waiting to be filled with data. People learn from people they love and remember the things that arouse emotion. If you think about how learning actually happens, you can discern many different processes. There is absorbing information. There is reflecting upon information as you reread it and think about it. There is scrambling information as you test it in discussion or try to mesh it with contradictory information. Finally there is synthesis, as you try to organize what you have learned into an argument or a paper.

Online education mostly helps students with Step 1. As Richard A. DeMillo of Georgia Tech has argued, it turns transmitting knowledge into a commodity that is cheap and globally available. But it also compels colleges to focus on the rest of the learning process, which is where the real value lies. In an online world, colleges have to think hard about how they are going to take communication, which comes over the Web, and turn it into learning, which is a complex social and emotional process.

Online education mostly helps students with Step 1. As Richard A. DeMillo of Georgia Tech has argued, it turns transmitting knowledge into a commodity that is cheap and globally available. But it also compels colleges to focus on the rest of the learning process, which is where the real value lies. In an online world, colleges have to think hard about how they are going to take communication, which comes over the Web, and turn it into learning, which is a complex social and emotional process.

How are they going to blend online information with face-to-face discussion, tutoring, debate, coaching, writing and projects? How are they going to build the social capital that leads to vibrant learning communities? Online education could potentially push colleges up the value chain — away from information transmission and up to higher things.

In a blended online world, a local professor could select not only the reading material, but do so from an array of different lecturers, who would provide different perspectives from around the world. The local professor would do more tutoring and conversing and less lecturing. Clayton Christensen of Harvard Business School notes it will be easier to break academic silos, combining calculus and chemistry lectures or literature and history presentations in a single course. The early Web radically democratized culture, but now in the media and elsewhere you’re seeing a flight to quality. The best American colleges should be able to establish a magnetic authoritative presence online. My guess is it will be easier to be a terrible university on the wide-open Web, but it will also be possible for the most committed schools and students to be better than ever.

DAVID BROOKS IS WRONG ABOUT ONLINE EDUCATION (ABSTRACT)

Joe Chuman – Just another WordPress.com site

May 4, 2012

And consider this: Online education has invaded the growing world of the charter school. We now have “virtual charter schools” to serve high schoolers and even younger students. And who is going to stay home to monitor Johnny’s or Jane’s relationship to a computer monitor five hours a day? It is a notoriously bad idea. But watch for a feeding frenzy of predatory capitalists ready to sacrifice countless young minds for ever-expanding profits. I hope David Brooks is pleased.

SAL KHAN, DAPHNE KOLLER, ANANT AGARWAL, AND THE SCHOOLS OF TOMORROW

The New York Times Schools for Tomorrow Conference, 9/17/2013.

As usual, the annual New York Times Schools for Tomorrow conference boasted a strong lineup of businesspeople, policymakers and academics on the pulse of educational innovation, performing for an audience of prematurely jaded journalists, ostentatiously Luddite faculty members, and businesspeople who thought their own companies should have been lauded from the stage.

Daphne Koller of Coursera, Sal Khan of Khan Academy, and Anant Agarwal of edX talked about the potential of their free course platforms, not as one-way broadcasters of video, but as analytics environments that collect vast amounts of data on the learning process and feed it back to curriculum developers for analysis.

On the other hand, Dean Florez of the 20 Million Minds foundation, was unsparing in pointing out that MOOCs as they exist today are not optimized to help the students he called “the 90 percent”–the nontraditional, working-two-jobs, first-in-their-families-to-go-to-college–the ones who truly need the convenience and affordability of online ed. Referencing the San Jose –Udacity pilot in which MOOCs offered to high school students in collaboration with San Jose State posted dismal pass rates, Florez said, “We need to dig in and work with the real students.”

The CEO Checkup

Alec Ross, formerly Hillary Clinton’s technology guru at the State Department who focuses on digital divide issues, made a point I hadn’t heard before in quite this way. He brought up the analogy of the “CEO Checkup,” a super-premium health care visit for an executive whose health is deemed to be of strategic interest to a company’s future, which costs tens of thousands of dollars and results in an overload of data. The fear is that wealthy parents will over-utilize the new computerized learning opportunities and diagnostics, resulting in highly individualized education programs and an even bigger edge for their kids, while poor kids struggle in schools that barely have Internet access.

The Power of Open–End Research

I was personally thrilled to see David Wiley, the pioneer of open educational content, now helping school districts and community colleges adopt free digital textbooks with Lumen Learning, and Candace Thille, who has taken her groundbreaking Open Learning Initiative from Carnegie Mellon to Stanford, on a panel about how the move to digital can, if done right, increase equity and access.

Thille in particular sounded a note that should resonate throughout the world of ed-tech. “Twenty hours in the lab can save you one hour in the library,” she quipped, pointing out that too many of the startups we see today are rushing forward with various models of instruction–game based, adaptive, what-have-you–without being grounded in an existing literature of decades of learning science. “That’s what I’ve spent the last 10 years of my life doing,” she said. “One thing we found is that learning is really complex…Once a colleague asked me, ‘why do you study learning? We all teach, it’s not rocket science.’ Well, actually it’s more complex than rocket science. Really understanding human learning at that episodic moment where you have change in thought is a complex process.”

Thille in particular sounded a note that should resonate throughout the world of ed-tech. “Twenty hours in the lab can save you one hour in the library,” she quipped, pointing out that too many of the startups we see today are rushing forward with various models of instruction–game based, adaptive, what-have-you–without being grounded in an existing literature of decades of learning science. “That’s what I’ve spent the last 10 years of my life doing,” she said. “One thing we found is that learning is really complex…Once a colleague asked me, ‘why do you study learning? We all teach, it’s not rocket science.’ Well, actually it’s more complex than rocket science. Really understanding human learning at that episodic moment where you have change in thought is a complex process.”

I was bemused to hear the reaction of her fellow panelist, Karen Cator, lately of the Obama Administration, Apple, and now Digital Promise. Although she heads up a well-funded nonprofit dedicated to spreading best practices on technology and education, she seemed to dismiss out of hand the notion that published academic research could find its way into the hands of edupreneurs or decision-makers. Karen, if you find Thille’s paper “An Evaluation of Accelerated Learning in the CMU Open Learning Initiative Course “Logic & Proofs,” too hard going, I give a quick overview in pp.120-123 of DIY U.

Recent Comments