K-12 Federal Education Programs

RACE TO THE TOP

On February 17, 2009, President Obama signed into law the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA), historic legislation designed to stimulate the economy, support job creation, and invest in critical sectors, including education. The ARRA lays the foundation for education reform by supporting investments in innovative strategies that are most likely to lead to improved results for students, long-term gains in school and school system capacity, and increased productivity and effectiveness.

The ARRA provides $4.35 billion for the Race to the Top Fund, a competitive grant program designed to encourage and reward States that are creating the conditions for education innovation and reform; achieving significant improvement in student outcomes, including making substantial gains in student achievement, closing achievement gaps, improving high school graduation rates, and ensuring student preparation for success in college and careers; and implementing ambitious plans in four core education reform areas:

- Adopting standards and assessments that prepare students to succeed in college and the workplace and to compete in the global economy;

- Building data systems that measure student growth and success, and inform teachers and principals about how they can improve instruction;

- Recruiting, developing, rewarding, and retaining effective teachers and principals, especially where they are needed most; and

- Turning around our lowest-achieving schools

Race to the Top will reward States that have demonstrated success in raising student achievement and have the best plans to accelerate their reforms in the future. These States will offer models for others to follow and will spread the best reform ideas across their States, and across the country.

Race to the Top will reward States that have demonstrated success in raising student achievement and have the best plans to accelerate their reforms in the future. These States will offer models for others to follow and will spread the best reform ideas across their States, and across the country.

States were given an incentive to adopt the Common Core Standards through the possibility of competitive federal Race to the Top grants. President Obama and Secretary of Education Arne Duncan announced the Race to the Top competitive grants on July 24, 2009, as a motivator for education reform. To be eligible, states had to adopt “internationally benchmarked standards and assessments that prepare students for success in college and the work place.” This meant that in order for a state to be eligible for these grants, the states had to adopt the Common Core State Standards or a similar career and college readiness curriculum. The competition for these grants provided a major push for states to adopt the standards. The adoption dates for those states that chose to adopt the Common Core State Standards Initiative are all within the two years following this announcement. The common standards are funded by the governors and state schools chiefs, with additional support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, and others. States are planning to implement this initiative by 2015 by basing at least 85% of their state curricula on the Standards. Wikipedia

NO CHILD LEFT BEHIND ACT OF 2001 (NCLB)

The No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB) is a United States Act of Congress that is a reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, which included Title 1, the government’s  flagship aid program for disadvantaged students. NCLB supports standard-based education reform based on the premise that setting high standards and establishing measurable goals can improve individual outcomes in education. The Act requires states to develop assessments in basic skills. States must give these assessments to all students at select grade levels in order to receive federal school funding. The Act does not assert a national achievement standard; standards are set by each individual state. NCLB expanded the federal role in public education through annual testing, annual academic progress, report cards, teacher qualifications, and funding changes.

flagship aid program for disadvantaged students. NCLB supports standard-based education reform based on the premise that setting high standards and establishing measurable goals can improve individual outcomes in education. The Act requires states to develop assessments in basic skills. States must give these assessments to all students at select grade levels in order to receive federal school funding. The Act does not assert a national achievement standard; standards are set by each individual state. NCLB expanded the federal role in public education through annual testing, annual academic progress, report cards, teacher qualifications, and funding changes.

Ability/ Achievement tests are used to evaluate students or workers understanding, comprehension, knowledge and/or capability in a particular area. They are used in academics, professions and many other areas. A general distinction is usually made between tests of ability/ aptitude (intelligence tests) versus tests of achievement (academic proficiency).

Critics have argued that the focus on standardized testing (all students in a state take the same test under the same condition) as the means of assessment encourages teachers to teach a narrow subset of skills that the teacher believes will increase test performance, rather than focus on acquiring deep understanding of the full, broad curriculum. For example, if the teacher knows that all of the questions on a math test are simple addition problems (e.g., what is 2 + 3?), then the teacher might not invest any class time on the practical applications of addition so that there will be more time for the material which is assessed on the test. This is colloquially referred to as “teaching to the test.” “Teaching to the test” has been observed to raise test scores, though not as much as other teaching techniques.

Many teachers who practice “teaching to the test” misinterpret the educational outcomes the tests are designed to measure. On two state tests (New York State and Michigan) and the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) almost two-thirds of eighth graders missed math word problems that required an application of the Pythagorean Theorem to calculate the distance between two points. The teachers correctly anticipated the content of the tests, but incorrectly assumed each test would present simplistic items rather than well-constructed, higher-order items.

Many teachers who practice “teaching to the test” misinterpret the educational outcomes the tests are designed to measure. On two state tests (New York State and Michigan) and the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) almost two-thirds of eighth graders missed math word problems that required an application of the Pythagorean Theorem to calculate the distance between two points. The teachers correctly anticipated the content of the tests, but incorrectly assumed each test would present simplistic items rather than well-constructed, higher-order items.

The practice of giving all students the same test, under the same conditions, has been accused of inherent cultural bias because different cultures may value different skills.

Many argue that local government had failed students, necessitating federal intervention to remedy issues like teachers teaching outside their areas of expertise, and complacency in the face of continually failing schools. Some local governments, notably that of New York state, have voiced support for NCLB provisions, because local standards had failed to provide adequate oversight over special education and NCLB would allow longitudinal data to be more effectively used to monitor Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP). States all over the United States have shown improvements in their progress as an apparent result of NCLB. For example, Wisconsin ranks first of all fifty states plus the District of Columbia, with ninety-eight percent of its schools achieving No Child Left Behind standards.

They worry that NCLB focuses too much on standardized testing and not enough on the work-based experience necessary for obtaining jobs in the future. Also, NCLB is measured essentially by a single test score, but IDEA calls for various measures of student success.

NCLB controls the portion of federal Title I funding based upon each school meeting annual set standards. Any participating school that does not make Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) for two years  must offer parents the choice to send their child to a non-failing school in the district, and after three years, must provide supplemental services, such as free tutoring or after-school assistance. After five years of not meeting AYP, the school must make dramatic changes to how the school is run, which could entail state-takeover.

must offer parents the choice to send their child to a non-failing school in the district, and after three years, must provide supplemental services, such as free tutoring or after-school assistance. After five years of not meeting AYP, the school must make dramatic changes to how the school is run, which could entail state-takeover.

Funding for school technology used in classrooms as part of NCLB is administered by the “Enhancing Education through Technology Program” (EETT). Funding sources are used for equipment, professional development and training for educators, and updated research. EETT allocates funds by formula to states. The states in turn reallocate 50% of the funds to local districts by Title I formula and 50% competitively.

While districts must reserve a minimum of 25% of all EETT funds for professional development, recent studies indicate that most EETT recipients use far more than 25% of their EETT funds to train teachers to use technology and integrate it into their curricula. In fact, EETT recipients committed more than $159 million in EETT funds towards professional development during the 2004–05 school year alone. Moreover, even though EETT recipients are afforded broad discretion in their use of EETT funds, surveys show that they target EETT dollars towards improving student achievement in reading and mathematics, engaging in data driven decision making, and launching online assessment programs.

In addition, the provisions of NCLB permitted increased flexibility for state and local agencies in the use of federal education money.

President Barack Obama released his blueprint for reform of the “Elementary and Secondary Education Act,” the precursor to No Child Left Behind, in March 2010. Specific revisions include providing funds for states to implement a broader range of assessments to evaluate advanced academic skills, including students’ abilities to;

- Conduct research

- Use technology

- Engage in scientific investigation

- Solve problems

- Communicate effectively

In addition, Obama is proposing that the NCLB legislation lessen its stringent accountability punishments to states by focusing more on student improvement. Improvement measures would encompass assessing all children appropriately, including English language learners, minorities, and special needs students. The school system would be re-designed to consider measures beyond reading and math tests; and would promote incentives to keep students enrolled in school through graduation, rather than encouraging student drop-out to increase AYP scores.

Obama’s objectives also entail lowering the achievement gap between Black and White students and also increasing the federal budget by $3 billion to help schools meet the strict mandates of the bill. There has also been a proposal, put forward by the Obama administration that states:

- Increase their academic standards after a dumbing-down period

- Focus on re-classifying schools that have been labeled as failing

- Develop a new evaluation process for teachers and educators

The federal government’s gradual investment in public social provisions provides the NCLB Act a forum to deliver on its promise to improve achievement for all of its students. Education critics argue that although the legislation is marked as an improvement to the ESEA in de-segregating the quality of education in schools, it is actually harmful. The legislation has become virtually the only federal social policy meant to address wide-scale social inequities, and its policy features inevitably stigmatize both schools attended by children of the poor and children in general.

Moreover, critics further argue that the current political landscape of this country, which favors market-based solutions to social and economic problems, has eroded trust in public institutions and has undermined political support for an expansive concept of social responsibility, which will subsequently result in a disinvestment in the education of the poor and privatization of American schools.

Moreover, critics further argue that the current political landscape of this country, which favors market-based solutions to social and economic problems, has eroded trust in public institutions and has undermined political support for an expansive concept of social responsibility, which will subsequently result in a disinvestment in the education of the poor and privatization of American schools.

Skeptics posit that NCLB has distinct political advantages for Democrats whose focus on accountability offers a way for them to continue to speak the language of equal opportunity, and to avoid being classified as the party of big government, special interests, and minority groups, a common accusation used by Republicans to discredit the traditional Democratic agenda. Opponents posit that NCLB has inadvertently shifted the debate on education and racial inequality to traditional political alliances. Consequently, major political discord remains between those who oppose federal oversight of state and local practices and those who view NCLB in terms of civil rights and educational equality.

In the plan, the Obama Administration responds to critiques that standardized testing fails to capture higher level thinking by outlining new systems of evaluation to capture more in depth assessments on student achievement. His plan came on the heels of the announcement of the “Race to the Top” initiative, a $4.35 billion reform program financed by the Department of Education through the “American Recovery and Reinvestment Act” of 2009.

Obama recognizes how accurate assessments “can be used to accurately measure student growth; to better measure how states, districts, schools, principals, and teachers are educating students; to help teachers adjust and focus their teaching; and to provide better information to students and their families.” He has pledged to support state governments in their efforts to improve standardize test provisions by upgrading the standards they are set to measure.

To do this, the federal government will provide grants to states to help them develop and implement assessments that are based on higher standards in order to more accurately measure school progress. This mirrors provisions in the “Race to the Top” program that require states to measure individual achievement through sophisticated data collection from kindergarten to higher education.

While Obama plans to improve the quality of standardized testing, he does not plan to eliminate the testing requirements and accountability measures produced by standardized tests. Rather, he provides additional resources and flexibility to meet new goals. Critics of Obama’s reform efforts maintain that high stakes testing will prove detrimental to the success of schools across the country by encouraging teachers to “teach to the test” and placing undue pressure on teachers and schools if benchmarks are failed to be met.

The reauthorization process has become somewhat of a controversy, as lawmakers and politicians continually debate about the changes that need to be made to the bill in order to make it work best for the country’s educational system.

WAIVERS

In 2012, President Obama granted waivers from NCLB requirements to several states. “In exchange for that flexibility, those states ‘have agreed to raise standards, improve accountability, and undertake essential reforms to improve teacher effectiveness,’ the White House said in a statement. Wikipedia

ELEMENTARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION ACT (ESEA)

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) was enacted April 11, 1965. It was passed as a part of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty and has been the most far reaching federal legislations affecting education ever passed by Congress. The act is an extensive statute that funds primary and secondary education, while explicitly forbidding the establishment of a national curriculum. It also emphasizes equal access to education and establishes high standards and accountability. In addition, the bill aims to shorten the achievement gaps between students by providing each child with fair and equal opportunities to achieve an exceptional education. As mandated in the act, the funds are authorized for professional development, instructional materials, for resources to support educational programs, and for parental involvement promotion. The act was originally authorized through 1970; however, the government has reauthorized the act every five years since its enactment. The current reauthorization of ESEA is the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, named and proposed by President George W. Bush. The ESEA also allows military recruiters access to 11th and 12th grade students’ names, addresses, and telephone listings when requested. Wikipedia

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) was enacted April 11, 1965. It was passed as a part of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty and has been the most far reaching federal legislations affecting education ever passed by Congress. The act is an extensive statute that funds primary and secondary education, while explicitly forbidding the establishment of a national curriculum. It also emphasizes equal access to education and establishes high standards and accountability. In addition, the bill aims to shorten the achievement gaps between students by providing each child with fair and equal opportunities to achieve an exceptional education. As mandated in the act, the funds are authorized for professional development, instructional materials, for resources to support educational programs, and for parental involvement promotion. The act was originally authorized through 1970; however, the government has reauthorized the act every five years since its enactment. The current reauthorization of ESEA is the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, named and proposed by President George W. Bush. The ESEA also allows military recruiters access to 11th and 12th grade students’ names, addresses, and telephone listings when requested. Wikipedia

Sections of the Original 1965 Act

TITLE I: Improving the Academic Achievement of the Disadvantaged

-

Title I, under No Child Left Behind, is designed to provide funds to school districts to ensure all children, especially disadvantaged children, receive a high-quality education and meet the prescribed state academic standards in core subject areas.

Approved programs through Title I need to provide additional academic support and opportunities to learn for all children. Funds may be used to extend and reinforce regular school curriculum including, but not limited to:

- Extra instruction in reading and math;

- Schoolwide improvement programs;

- Targeted assistance programs;

- Special preschool programs;

- After-school programs; and

- Summer programs.

For more information regarding Title I, please visit: (www.ed.gov/programs/titleiparta)

Study Island provides programs that help schools meet the goals of Title I by:

- Promoting mastery of academic standards for all students through lessons and assessments built from state standards.

- Increasing accountability of students and schools by providing detailed reports that show where students, classes, or schools stand in mastery of the required standards.

- Providing guidance and opportunities for individualized instruction in reported areas of weakness.

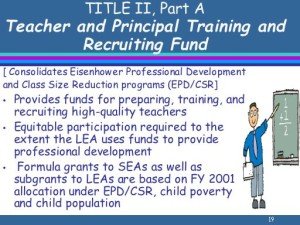

- TITLE II: Preparing, Training, and Recruiting High Quality Teachers and Principals

-

Title II funds are to be used by schools and districts to increase student achievement by improving the quality of teachers and administrators through high-quality, research-based professional development. Title II also provides funds for schools to hold local educational agencies and schools accountable for improvements in student academic achievement.

For more information regarding Title II, please visit: (www.ed.gov/policy/elsec/leg/esea02)

Study Island provides programs that help schools meet the goals of Title II by:

- Enhancing teacher quality through professional development designed to improve student achievement using research-based programs directly built from state standards.

- Promoting communication among parents, teachers, administrators and students through the use of technology.

- TITLE IID: Enhancing Education Through Technology (EETT)

-

The purpose of Title IID funds is to assist schools and districts in implementing and supporting a system that uses technology to improve student academic achievement. These initiatives should provide an integration of technology effectively in lessons and curriculum that are aligned with state standards.

For more information regarding Title II, please visit: (www.ed.gov/policy/elsec/leg/esea02)

Study Island provides programs that help schools meet the goals of Title II by:

- Enhancing teacher quality through professional development designed to improve student achievement using research-based programs directly built from state standards.

- Promoting communication among parents, teachers, administrators and students through the use of technology.

- TITLE III: Language Instruction for Limited English Proficient Children and Immigrant Students

-

Title III (ELL) programs are designed to ensure children who are limited English proficient, including immigrant children, meet the same challenging academic content standards all other children are expected to meet.

For more information regarding Title III, please visit: (www.ed.gov/policy/elsec/leg/esea02)

Study Island provides programs that help schools meet the goals of Title III by:

- Providing schools with technology and tools to underserved populations, including disadvantaged, illiterate, limited English proficient populations, and individuals with disabilities in mastering state standards.

- Providing standards-based, academic content instruction and assessment programs for all children.

- Measuring a school or district’s progress in meeting their AYP (Adequate Yearly Progress) goals.

- Allowing students to work the program at their own pace.

- Providing built-in remediation and building blocks for struggling students.

- TITLE IV: 21st Century Schools

-

Title IV funds are to be used by schools and districts to foster a safe education environment, address the needs of at-risk students, and enhance the school-to-home connection. Title IV funds are also used to offer a broad array of additional services, programs, and activities designed to reinforce and complement the regular academic program of students.

For more information regarding Title IV, please visit: (www.ed.gov/policy/elsec/leg/esea02)

Study Island provides programs that help schools meet the goals of Title IV by:

- Providing programs that are designed to assist students in the mastery of state standards through review, remediation, and enrichment activities during out-of-school time.

- Extending the learning day and allowing access to Study Island programs 24/7/365 when school is not in session through the use of technology.

- Contributing to the reduction of drug use and violence in the community by offering exciting, engaging, efficient, and effective standards-based learning opportunities and activities.

- TITLE V, Part A: Promoting Informed Parental Choice and Innovative Programs

-

Title V, Part A provides a continuing source of innovation and educational improvement in schools and districts. This includes technology programs and activities that expand learning opportunities through best-practice models designed to improve classroom learning and teaching. Title V, Part A funds may be used on programs for the development or acquisition and use of instructional and educational materials, including library services and materials, academic assessments, reference materials, computer software and hardware for instructional use, and other curricular materials that are tied to high academic standards, that will be used to improve student achievement, and that are part of an overall education reform program.

For more information regarding Title V, Part A, please visit: (www.ed.gov/policy/elsec/leg/esea02)

Study Island provides programs that help schools meet the goals of Title V, Part A by:

- Providing schools with technology and tools that give teachers the knowledge and skills to provide students with the opportunity to meet state standards and improve assessment scores.

- Offering professional development to improve teacher and school performance by using technology effectively in the classrooms.

- Providing schools with technology programs and activities for the academic achievement of underserved populations, including disadvantaged, illiterate, limited English proficient populations, and individuals with disabilities.

- TITLE VI, Part B: Rural Education Initiative

-

Title VI, Part B contains Rural Education Achievement Program initiatives designed to help rural districts, in part by addressing:

- Teacher recruitment and retention;

- Professional development;

- Educational technology; and

- Parental involvement activities.

For more information regarding Title VI, Part B, please visit: (www.2.ed.gov/policy/elsec/leg/esea02)

Study Island provides programs that help schools meet the goals of Title VI, Part B by:

- Offering professional development to improve teacher quality by using technology effectively in the classroom.

- Providing parents with meaningful opportunities to participate in their child’s education by allowing access to the program from home as well as emailing them real-time reports.

- TITLE VII: Indian, Native Hawaiian, and Alaskan Native Education

-

Title VII funding is designed to support programs in schools and districts to meet the unique educational and cultural needs of Alaska Native and American Indian students. These programs must help these children meet the same challenging state standards as all other students. Programs that qualify for Title VII funding may include early childhood and enrichment programs.

For more information regarding Title VII, please visit: (www.ed.gov/policy/elsec/leg/esea02)

Study Island provides programs that help schools meet the goals of Title VII by:

- Providing standards-based, academic content instruction and assessment programs for all children.

- Providing guidance and opportunities for individualized instruction and target teaching designed to help students master standards and boost test scores.

- IDEA: Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

-

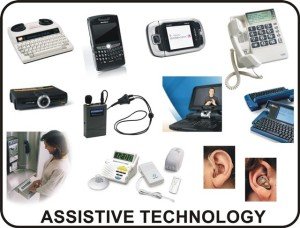

IDEA is a federal law designed to protect students with disabilities by providing funding to ensure those students receive a free appropriate public education (FAPE). The intention is to make sure every child with disabilities receives an education that prepares them for advanced levels of education, employment, and independent living. IDEA funds are used to provide early intervention, special education, and related services, including assistive technology.

For more information regarding IDEA, please visit: (www.dea.ed.gov)

Study Island provides programs that help schools meet the goals of IDEA by:

- Providing schools with technology and tools to serve underserved populations, including disadvantaged, illiterate, limited English proficient populations, and individuals with disabilities.

- Providing programs that are designed to assist students in the mastery of state standards through review, remediation, and enrichment activities.

- Offering special needs support including text-to-speech functionality, larger font sizes, and fewer answer choices.

- HEAD START

New Titles Created by Early Amendments to 1965 Law

2008 No Child Left Behind Blue Ribbon School Logo

1966 amendments (Public Law 89-750)

Title VI – Aid to Handicapped Children (1965 title VI becomes Title VII)

1967 amendments (Public Law 90-247)

Title VII – Bilingual Education Programs (1966 title VII becomes Title VIII)

TITLE I

Overview

Title I (“Title One”), a provision of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act passed in 1965 is a program created by the United States Department of Education to distribute funding to schools and school districts with a high percentage of students from low-income families. Funding is distributed first to State Education Agencies (SEAs) which then allocate funds to Local Education Agencies (LESs) which in turn dispense funds to public schools in need. Title I also helps children from families that have migrated to the United States and youth from intervention programs who are neglected or at risk of abuse.

Agencies (LESs) which in turn dispense funds to public schools in need. Title I also helps children from families that have migrated to the United States and youth from intervention programs who are neglected or at risk of abuse.

The act appropriates money for educational purposes for the next five fiscal years until it is reauthorized. In addition, Title I appropriates money to the education system for prevention of dropouts and the improvement of schools. These appropriations are carried out for five fiscal years until reauthorization.

According to the National Center for Educational Statistics, to be an eligible Title I school, at least 40% of a school’s students must be from low-income families who qualify under the United States Census’s definition of low-income, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

Title I mandates services both to eligible public school students and eligible private school students. This is outlined in section 1120 of Title I, Part A of the ESEA as amended by the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB). Title I states that it gives priority to schools that are in obvious need of funds, low-achieving schools, and schools that demonstrate a commitment to improving their education standards and test scores.

There are two types of assistance that can be provided by Title I funds. The first is a “schoolwide program” in which schools can dispense resources in a flexible manner. The second is a “targeted assistance program” which allows schools to identify students who are failing or at risk of failing.

Assistance for school improvement includes government grants, allocations, and reallocations based on the school’s willingness to commit to improving their standing in the educational system. Each educational institution requesting these grants must submit an application that describes how these funds will be used in restructuring their school for academic improvement.

Assistance for school improvement includes government grants, allocations, and reallocations based on the school’s willingness to commit to improving their standing in the educational system. Each educational institution requesting these grants must submit an application that describes how these funds will be used in restructuring their school for academic improvement.

Schools receiving Title I funding are regulated by federal legislation. Most recently, this legislation includes the No Child Left Behind Act which was passed in 2001. In the 2006-2007 school year, Title I provided assistance to over 17 million students who range from kindergarten through twelfth grade. The majority of the funds (60%) were given to students in kindergarten through fifth grade. The next highest group that received funding were students in sixth through eighth grade (21%). Finally, 16% of the funds went to students in high school with 3% provided to students in preschool.

TITLE II

TITLE II: Preparing, Training, and Recruiting High Quality Teachers and Principals

Title II funds are to be used by schools and districts to increase student achievement by improving the quality of teachers and administrators through high-quality, research-based professional development. Title II also provides funds for schools to hold local educational agencies and schools accountable for improvements in student academic achievement.

TITLE IID: Enhancing Education through Technology (EETT)

The purpose of Title IID funds is to assist schools and districts in implementing and supporting a system that uses technology to improve student academic achievement. These initiatives should  provide an integration of technology effectively in lessons and curriculum that are aligned with state standards.

provide an integration of technology effectively in lessons and curriculum that are aligned with state standards.

(1) PRIMARY GOAL– The primary goal of this part is to improve student academic achievement through the use of technology in elementary schools and secondary schools.

(2) ADDITIONAL GOALS– The additional goals of this part are the following:

(A) To assist every student in crossing the digital divide by ensuring that every student is technologically literate by the time the student finishes the eighth grade, regardless of the student’s race, ethnicity, gender, family income, geographic location, or disability.

(B) To encourage the effective integration of technology resources and systems with teacher training and curriculum development to establish research-based instructional methods that can be widely implemented as best practices by State educational agencies and local educational agencies.

HEAD START PROGRAM

Launched in 1965 by its creator and first director Jule Sugarman, Head Start was originally conceived as a catch-up summer-school program that would teach low-income children in a few weeks what they needed to know to start kindergarten. Experience showed that six weeks of preschool couldn’t make up for five years of poverty. The Head Start Act of 1981 expanded the program. The program was further revised when it was reauthorized in December, 2007. Head Start is one of the longest-running programs to address systemic poverty in the United States. As of late 2005, more than 22 million pre-school aged children had participated. In 2011 its effectiveness was put into question by a Department of Health and Human Services study. There are long waits to get into early-childhood-enrichment programs like Head Start. Wikipedia

Launched in 1965 by its creator and first director Jule Sugarman, Head Start was originally conceived as a catch-up summer-school program that would teach low-income children in a few weeks what they needed to know to start kindergarten. Experience showed that six weeks of preschool couldn’t make up for five years of poverty. The Head Start Act of 1981 expanded the program. The program was further revised when it was reauthorized in December, 2007. Head Start is one of the longest-running programs to address systemic poverty in the United States. As of late 2005, more than 22 million pre-school aged children had participated. In 2011 its effectiveness was put into question by a Department of Health and Human Services study. There are long waits to get into early-childhood-enrichment programs like Head Start. Wikipedia

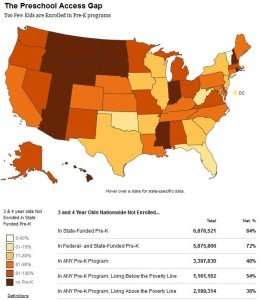

PRESCHOOL FOR ALL INITIATIVE

Early Head Start-Child Care

President Obama wants Congress to expand access to preschool for every child in America. Beginning at birth and continuing to age 5 the “Preschool for All” initiative will improve quality and expand access to preschool, through a cost sharing partnership with all 50 states, to provide all low- and moderate-income four-year-olds with high-quality preschool, while encouraging states to serve additional four-year-olds from middle-class families.

The initiative also promotes access to full-day kindergarten and high-quality early education programs for children under age four. The goal is to reach all low- and moderate-income four-year olds from families at or below 200% of poverty. The plan is to maintain and build on current Head Start investments, to support a greater share of infants, toddlers, and three-year olds in America’s Head Start centers, while state preschool settings will serve a greater share of four-year olds.

The U.S. Department of Education will allocate dollars (Child Care and Development Block Grants) to states based their share of four-year olds from low- and moderate-income families and funds would be distributed to local school districts and other partner providers to implement the program. This new “Early Head Start-Child Care” partnership will be funded through competitive grants that will support communities that expand the availability of Early Head Start and child care providers that can meet the highest standards of quality for infants and toddlers, serving children from birth through age 3.

would be distributed to local school districts and other partner providers to implement the program. This new “Early Head Start-Child Care” partnership will be funded through competitive grants that will support communities that expand the availability of Early Head Start and child care providers that can meet the highest standards of quality for infants and toddlers, serving children from birth through age 3.

The proposal would also include an incentive for states to broaden participation in their public preschool program for additional middle-class families, which states may choose to reach and serve in a variety of ways, such as a sliding-scale arrangement.

The Head Start and Early Head Start programs goal is to reach an additional 61,000 children and enrollment has nearly doubled under this Administration. Needed reform to the program has begun by identifying lower-performing grantees and ensuring that those failing to meet new, rigorous benchmarks face new competition for continued federal funding.

In order to access federal funding, states would be required to meet quality benchmarks that are linked to better outcomes for children, which include:

- State-level standards for early learning

- Qualified teachers for all preschool classrooms

- A plan to implement comprehensive data and assessment systems

Preschool programs across the states have to meet common and consistent standards for quality across all programs, including:

- Well-trained teachers, who are paid comparably to K-12 staff

- Small class sizes and low adult to child ratios

- A rigorous curriculum

- Comprehensive health and related services

- Effective evaluation and review of programs

Since only 6 out of 10 of America’s kindergarten students have access to a full day of learning funds under this program may also be used to expand full-day kindergartens that provide rigorous benchmarks and standards once states have provided preschool education to low- and moderate-income four year-olds.

Since only 6 out of 10 of America’s kindergarten students have access to a full day of learning funds under this program may also be used to expand full-day kindergartens that provide rigorous benchmarks and standards once states have provided preschool education to low- and moderate-income four year-olds.

Funds will be awarded through Early Head Start on a competitive basis to enhance and support early learning settings; provide new, full-day, comprehensive services that meet the needs of working families; and prepare children for the transition into preschool. This strategy – combined with an expansion of publicly funded preschool education for four-year olds – will ensure a cohesive and well-aligned system of early learning for children from birth to age five.

The Evidence-based Home Visiting Initiative

The Administration’s “Evidence-based Home Visiting Initiative,” through which states are implementing voluntary programs that provide nurses, social workers, and other professionals to meet with at-risk families in their homes and connect them to assistance that impacts a child’s health, development, and ability to learn is proposing to expand.

Obama has already committed $1.5 billion to expand home visitation to hundreds of thousands of America’s most vulnerable children and families in all 50 states. The President will pursue substantial investments to expand these important programs to reach additional families in need.

substantial investments to expand these important programs to reach additional families in need.

These programs have been critical in improving maternal and child health outcomes in the early years, leaving long-lasting, positive impacts on parenting skills; children’s cognitive, language, and social-emotional development; and school readiness. This will help ensure that our most vulnerable Americans are on track from birth, and that later educational investments rest upon a strong foundation.

Race to the Top – Early Learning Challenge

The Early Learning Challenge has rewarded 14 states that have agreed to raise the bar on the quality of their early childhood education programs, establish higher standards across programs and provide critical links with health, nutrition, mental health, and family support for our neediest children.

Challenges

President Obama has been a steadfast supporter of Head Start and Early Head Start. However, pressure to resolve our nation’s economic problems is growing, and the President and members of his administration will be forced to make difficult decisions about how to spend federal dollars. Many are against federal spending on programs for our most vulnerable children and their families. There have been calls for ending Head Start, arguing that its positive effects fade away after a few months.

READING IS FUNDAMENTAL, INC.

“Reading is Fundamental” is the oldest and largest nonprofit literacy organization in the United States. Founded in 1966, it is based in Washington D.C. RIF’s community volunteers in every state and U.S. territory provide 4.5 million children with 16 million new, free books and literacy resources each year. RIF’s priority is impoverished children from birth to age 8 years.

“Reading is Fundamental” is the oldest and largest nonprofit literacy organization in the United States. Founded in 1966, it is based in Washington D.C. RIF’s community volunteers in every state and U.S. territory provide 4.5 million children with 16 million new, free books and literacy resources each year. RIF’s priority is impoverished children from birth to age 8 years.

All RIF programs combine three essential elements to foster children’s literacy: reading motivation, family and community involvement, and the excitement of choosing free books to keep. RIF’s accomplishments are due in part to the generous financial assistance by the U.S. Department of Education, corporations, foundations, community organizations, and thousands of individuals.

In 1966, former teacher Margaret McNamara brought a bag of used books to four boys in Washington D.C., whom she tutored in reading. When she told the children they could each select a book to keep, their astonishment and delight led her to discover that these children, and many of their classmates, had never owned any books. By that summer, McNamara had gathered a group of school volunteers, and on November 3, 1966, they launched the book distribution and reading motivation program they called Reading Is Fundamental. From November 1966 through the early 1970s, RIF expanded from a pilot project at three elementary schools in Washington, D.C., to a program reaching children in 60 of the city’s public schools. Its well-known slogan during those times was “Reading is FUNdamental”.

children they could each select a book to keep, their astonishment and delight led her to discover that these children, and many of their classmates, had never owned any books. By that summer, McNamara had gathered a group of school volunteers, and on November 3, 1966, they launched the book distribution and reading motivation program they called Reading Is Fundamental. From November 1966 through the early 1970s, RIF expanded from a pilot project at three elementary schools in Washington, D.C., to a program reaching children in 60 of the city’s public schools. Its well-known slogan during those times was “Reading is FUNdamental”.

In 1975, the U.S. Congress created the Inexpensive Book Distribution Program (IBDP) which provides federal matching funds to sites that qualify for RIF’s national book program. Today, through its contract with the United States Department of Education to operate the IBDP, now supplemented with private funds, RIF programs operate in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Guam. RIF is also affiliated with programs in Argentina and the United Kingdom.

In 2004 Kappa Kappa Gamma a national women’s fraternity, selected RIF as its national philanthropy. Together, Kappa and RIF have developed the “Reading Is Key” program, through which children are exposed to new books. The America Reads Challenge is a four-year national campaign to promote the importance of all children reading well and independently by the end of the third grade.

In 2004 Kappa Kappa Gamma a national women’s fraternity, selected RIF as its national philanthropy. Together, Kappa and RIF have developed the “Reading Is Key” program, through which children are exposed to new books. The America Reads Challenge is a four-year national campaign to promote the importance of all children reading well and independently by the end of the third grade.

RIF’s flagship service is Books for Ownership (formerly known as the National Book Program), which also supplies children with free paperback books. RIF also offers several special literacy services which, in addition to supplying the services of the Books for Ownership program, target their efforts to specific age groups or populations. RIF serves children at a wide range of venues, including schools, libraries, childcare centers, Head Start programs, parks, community centers, health clinics, migrant camps, and domestic shelters. Wikipedia

FEDERAL SUPPORT OF DIGITAL AND OPEN CONTENT

While K-12 instructional materials decisions are the purview of states and districts, the federal government advocates for digital and open content by encouraging its use and by requiring or incenting its inclusion as a component of select grant programs.

Two national plans crucial to education—the National Education Technology Plan, “Transforming American Education: Learning Powered by Technology,” and the National Broadband Plan,  “Connecting America”— provide recommendations focused on digital and open content. The National Education Technology Plan, for example, recommends that entities support the development and use of OER and participate “in efforts to ensure that transitioning from predominantly print-based classrooms to digital learning environments promotes organized, accessible, easy-to-distribute, and easy-to-use content and learning resources.”

“Connecting America”— provide recommendations focused on digital and open content. The National Education Technology Plan, for example, recommends that entities support the development and use of OER and participate “in efforts to ensure that transitioning from predominantly print-based classrooms to digital learning environments promotes organized, accessible, easy-to-distribute, and easy-to-use content and learning resources.”

The National Broadband Plan is no less ambitious: “The US Department of Education should consider investment in open licensed and public domain software alongside traditionally licensed solutions, while taking into account the long-term effects on the marketplace.”

A typical example of a program requirement in a grant program was in the US Department of Education’s “Race to the Top Fund,” where all work developed under the grant that was not protected by law or agreement had to be made freely available to others. The “Race to the Top Assessment Program” took this requirement a step further by expressly stating that the assessment content developed under the grant be made widely available, “including to States that are not part of consortia receiving funds under this competition as well as to commercial organizations…” Other recent examples can be found in other US Department of Education programs, which included competitive grant priorities in support of OER, including for “Strengthening Institutions,” “Investing in Innovation (i3) Fund,” and “Upward Bound.”

Perhaps the most prominent example of federal support for OER, however, is via the Department of Labor’s “Trade Adjustment Assistance Act Community College and Career Training Grant Program” for which recipients must license all of their program output under a “Creative Commons CC BY License.” The Department of Labor will create an online public repository for all these materials, making them even more accessible. (SETDA)

Perhaps the most prominent example of federal support for OER, however, is via the Department of Labor’s “Trade Adjustment Assistance Act Community College and Career Training Grant Program” for which recipients must license all of their program output under a “Creative Commons CC BY License.” The Department of Labor will create an online public repository for all these materials, making them even more accessible. (SETDA)

CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES IN NO CHILD LEFT BEHIND

The No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) includes incentives to reward schools showing progress for students with disabilities and other measures to fix or provide students with alternative options than schools not meeting the needs of the disabled population. The law is written so that the scores of students with Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) and 504 plans are counted just as other students’ scores are counted. Schools have argued against having disabled populations involved in their AYP measurements because they claim that there are too many variables involved.

schools not meeting the needs of the disabled population. The law is written so that the scores of students with Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) and 504 plans are counted just as other students’ scores are counted. Schools have argued against having disabled populations involved in their AYP measurements because they claim that there are too many variables involved.

Aligning the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act with NCLB

Stemming from the Education for all Handicapped Children Act (EAHCA) of 1975, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act was enacted in its first form in 1997, and then reenacted with new education aspects in 2006 (although still referred to as IDEA 2004). It kept the EAHCA requirements of free and accessible education for all children. The 2004 IDEA authorized formula grants to states and discretionary grants for  research, technology and training. It also required schools to use research-based interventions to assist students with disabilities.

research, technology and training. It also required schools to use research-based interventions to assist students with disabilities.

The amount of funding each school would receive from its “Local Education Agency” for each year would be divided by the number of children with disabilities and multiplied by the number of students with disabilities participating in the schoolwide programs.

Particularly since 2004, policymakers have sought to align IDEA with NCLB. The most obvious points of alignment include the shared requirements for Highly Qualified Teacher, for establishment of goals for students with special needs, and for assessment levels for these students. In 2004, George Bush signed provisions that would define for both of these acts what was considered a “highly qualified teacher.”

Positive effects of NCLB for students with disabilities

The National Council for Disabilities (NCD) looks at how NCLB and IDEA are improving outcomes for students with disabilities. The effects they investigate include reducing the number of students who drop out, increasing graduation rates, and effective strategies to transition students to post-secondary education. Their studies have reported that NCLB and IDEA have changed the attitudes and expectations for students with disabilities. They are pleased that students are finally included in state assessment and accountability systems. NCLB made assessments be taken “seriously,” they found, as now assessments and accommodations are under review by administrators.

Another organization that found positive correlations between NCLB and IDEA was the National Center on Educational Outcomes. It published a brochure for parents of students with disabilities about how the two (NCLB & IDEA) work well together because they “provide both individualized instruction and school accountability for students and disabilities.” They specifically highlight the new focus on “shared responsibility of general and special education teachers,” forcing schools to have disabled students more on their radar.” They do acknowledge, however, that for each student to “participate in the general curriculum [of high standards for all students] and make progress toward proficiency,” additional time and effort for coordination are needed. The National Center on Educational Outcomes reported that now disabled students will receive “the academic attention and resources they deserved.”

Another organization that found positive correlations between NCLB and IDEA was the National Center on Educational Outcomes. It published a brochure for parents of students with disabilities about how the two (NCLB & IDEA) work well together because they “provide both individualized instruction and school accountability for students and disabilities.” They specifically highlight the new focus on “shared responsibility of general and special education teachers,” forcing schools to have disabled students more on their radar.” They do acknowledge, however, that for each student to “participate in the general curriculum [of high standards for all students] and make progress toward proficiency,” additional time and effort for coordination are needed. The National Center on Educational Outcomes reported that now disabled students will receive “the academic attention and resources they deserved.”

Particular research has been done on how the laws impact students who are deaf or hearing-impaired. First, the legislation forces schools to be responsible for how these students with disabilities are scoring, thus emphasizing “student outcomes instead of placement.” It also puts the public’s eye on how outside programs can be utilized to improve outcomes for this underserved population, and has thus prompted more research on the effectiveness of certain in- and out-of-school interventions. For example, NCLB requirements have made researchers begin to study the effects of read aloud or interpreters on both reading and mathematics assessments and on having students sign responses that are then recoded by a scribe.

Still, research thus far on the positive effects of NCLB/IDEA is limited. It has been aimed at young students in an attempt to find strategies to help them learn to read. Evaluations also have included a limited number of students, which make it very difficult to draw conclusions to a broader group. Evaluations also focus only on one type of disabilities.

Negative effects of NCLB for students with disabilities

The National Council for Disabilities had reservations about how the regulations of NCLB fit with those of IDEA. One concern is how schools will make effective interventions and strategies when NCLB calls for group accountability rather than individual student attention. The Individual nature of IDEA is “inconsistent with the group nature of NCLB. They worry that NCLB focuses too much on standardized testing and not enough on the work-based experience necessary for obtaining jobs in the future. Also, NCLB is measured essentially by a single test score, but IDEA calls for various measures of student success.

IDEA’s focus on various measures stems from its foundation in IEPs for students with disabilities. An IEP is designed to give students with disabilities individual goals that are often not on their grade level. An IEP is intended for “developing goals and objectives that correspond to the needs of the student, and ultimately choosing a placement in the least restrictive environment possible for the student. Under the IEP, students could be able to legally have lowered success criteria for academic success.

A 2006 report by the Center for Evaluation and Education Policy (CEEP) and Indian Institute on Disability and Community indicated that most states were not making AYP because of special education subgroups even though progress had been made toward that end. This was in effect pushing schools to cancel the inclusion model and keep special education students separate. “IDEA calls for individualized curriculum and assessments that determine success based on growth and improvement each year. NCLB, in contrast, measures all students by the same markers, which are based not on individual improvement but by proficiency in math and reading,” the study states.

A 2006 report by the Center for Evaluation and Education Policy (CEEP) and Indian Institute on Disability and Community indicated that most states were not making AYP because of special education subgroups even though progress had been made toward that end. This was in effect pushing schools to cancel the inclusion model and keep special education students separate. “IDEA calls for individualized curriculum and assessments that determine success based on growth and improvement each year. NCLB, in contrast, measures all students by the same markers, which are based not on individual improvement but by proficiency in math and reading,” the study states.

When interviewed with the Indiana University Newsroom, author of the CEEP report Sandi Cole said, “The system needs to make sense. Don’t we want to know how much a child is progressing towards the standards?…We need a system that values learning and growth over time, in addition to helping students reach high standards. Cole found in her survey that NCLB encourages teachers to teach to the test, limiting curriculum choices/options, and to use the special education students as a “scapegoat” for their school not making AYP. In addition, Indiana administrators who responded to the survey indicated that NCLB testing has led to higher numbers of students with disabilities dropping out of school.

towards the standards?…We need a system that values learning and growth over time, in addition to helping students reach high standards. Cole found in her survey that NCLB encourages teachers to teach to the test, limiting curriculum choices/options, and to use the special education students as a “scapegoat” for their school not making AYP. In addition, Indiana administrators who responded to the survey indicated that NCLB testing has led to higher numbers of students with disabilities dropping out of school.

Legal journals have also commented on the incompatibility of IDEA and NCLB; some say the acts may never be reconciled with one another. They point out that an IEP is designed specifically for individual student achievement, which gives the rights to parents to ensure that the schools are following the necessary protocols of Free Access to Public Education (FAPE). They worry that not enough emphasis is being placed on the child’s IEP with this setup.

In Board of Education for Ottawa Township High School District 140 v. Spelling, two Illinois school districts and parents of disabled students challenged the legality of NCLB’s testing requirements in light of IDEA’s mandate to provide students with individualized education. Although students there were aligned with “proficiency” to state standards, students did not meet requirements of their IEP. Their parents feared that students were not given right to FAPE. The case questioned which was a better indicator of progress – standardized test measures, or IEP measures? It concluded that since some students may never test on grade level, all students with disabilities should be given more options and accommodations with standardized testing than they are currently receiving.

MAINSTREAMING (EDUCATION)

In the context of education, mainstreaming is the practice of educating students with special needs in regular classes during specific time periods based on their skills. This means regular education classes are combined with special education classes. Schools that practice mainstreaming believe that students with special needs who cannot function in a regular classroom to a certain extent “belong” to the special education environment.

In the context of education, mainstreaming is the practice of educating students with special needs in regular classes during specific time periods based on their skills. This means regular education classes are combined with special education classes. Schools that practice mainstreaming believe that students with special needs who cannot function in a regular classroom to a certain extent “belong” to the special education environment.

Access to a special education classroom, often called a “self-contained classroom or resource room”, is valuable to the student with a disability. Students have the ability to work one-on-one with special education teachers, addressing any need for remediation during the school day. Many researchers, educators and parents have advocated the importance of these classrooms amongst political environments that favor their elimination.

Advantages

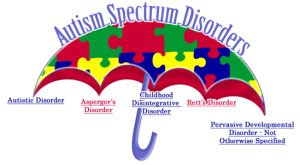

Proponents of both mainstreaming and the related philosophy of educational inclusion assert that educating children with disabilities alongside their non-disabled peers fosters understanding and tolerance better preparing students of all abilities to function in the world beyond school. It is believed that educating children with disabilities alongside their non-disabled peers facilitates access to the general curriculum for children with disabilities. Studies show that students with disabilities who are mainstreamed have. Mainstreaming has shown to be more academically effective than exclusion practices; has shown disabled students to be more confident and display qualities of raised self-efficacy; and allows students with disabilities to learn social skills through observation, gain a better understanding of the world around them, and become a part of the “regular” community. Mainstreaming is particularly beneficial for children with autism and ADHD as it opens the lines of communication between those students with disabilities and their peers. If they are included into classroom activities, all students become more sensitive to the fact that these students may need extra assistance.

peers fosters understanding and tolerance better preparing students of all abilities to function in the world beyond school. It is believed that educating children with disabilities alongside their non-disabled peers facilitates access to the general curriculum for children with disabilities. Studies show that students with disabilities who are mainstreamed have. Mainstreaming has shown to be more academically effective than exclusion practices; has shown disabled students to be more confident and display qualities of raised self-efficacy; and allows students with disabilities to learn social skills through observation, gain a better understanding of the world around them, and become a part of the “regular” community. Mainstreaming is particularly beneficial for children with autism and ADHD as it opens the lines of communication between those students with disabilities and their peers. If they are included into classroom activities, all students become more sensitive to the fact that these students may need extra assistance.

Disadvantages

Compared to fully included students with disabilities, those who are mainstreamed for only certain classes or certain times may feel conspicuous or socially rejected by their classmates. They may become targets for bullying. Mainstreamed students may feel embarrassed by the additional services they receive in a regular classroom, such as an aide to help with written work or to help the student manage behaviors. Some students with disabilities may feel more comfortable in an environment where most students are working at the same level or with the same supports. Students with autism spectrum disorders are more frequently the target of bullying than non-autistic students, especially when their educational program brings them into regular contact with non-autistic students.

Compared to fully included students with disabilities, those who are mainstreamed for only certain classes or certain times may feel conspicuous or socially rejected by their classmates. They may become targets for bullying. Mainstreamed students may feel embarrassed by the additional services they receive in a regular classroom, such as an aide to help with written work or to help the student manage behaviors. Some students with disabilities may feel more comfortable in an environment where most students are working at the same level or with the same supports. Students with autism spectrum disorders are more frequently the target of bullying than non-autistic students, especially when their educational program brings them into regular contact with non-autistic students.

Costs

Schools are required to provide special education services but may not be given additional financial resources. The per-student cost of special education is high. The U.S.’s 2005 Special Education  Expenditures Program (SEEP) indicates that the cost per student in special education ranges from a low of $10,558 for students with learning disabilities to a high of $20,095 for students with multiple disabilities. The average cost per pupil for a regular education with no special education services is $6,556. Therefore, the average expenditure for students with learning disabilities is 1.6 times that of a general education student.

Expenditures Program (SEEP) indicates that the cost per student in special education ranges from a low of $10,558 for students with learning disabilities to a high of $20,095 for students with multiple disabilities. The average cost per pupil for a regular education with no special education services is $6,556. Therefore, the average expenditure for students with learning disabilities is 1.6 times that of a general education student.

Careful attention must be given as well to combinations of students with disabilities in a mainstreamed classroom. For example, a student with conduct disorder may not combine well with a student with autism, while putting many children with dyslexia in the same class may prove to be particularly efficient.

History of Mainstreaming in US Schools

Before the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHA) was enacted in 1975, U.S. public schools educated only 1 out of 5 children with disabilities. Approximately 200,000 children with disabilities such as deafness and mental retardation lived in state institutions that provided limited or no educational or rehabilitation services, and more than one million children were excluded  from school. Another 3.5 million children with disabilities attended school but did not receive the educational services they needed. Many of these children were segregated in special buildings or programs that neither allowed them to interact with non-disabled students nor provided them with even basic academic skills.

from school. Another 3.5 million children with disabilities attended school but did not receive the educational services they needed. Many of these children were segregated in special buildings or programs that neither allowed them to interact with non-disabled students nor provided them with even basic academic skills.

The EHA later renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), required schools to provide specialized educational services to children with disabilities. The ultimate goal was to help these students live more independent lives in their communities, primarily by mandating access to the general education standards of the public school system.

Initially, children with disabilities were often placed in heterogeneous “special education” classrooms, making it difficult for any of their difficulties to be addressed appropriately. In the 1980s, the mainstreaming model began to be used more often as a result of the requirement to place children in the least restrictive environment. Students with relatively minor disabilities were integrated into regular classrooms, while students with major disabilities remained in segregated special classrooms, with the opportunity to be among normal students for up to a few hours each day. Many parents and educators favored allowing students with disabilities to be in classrooms along with their nondisabled peers.

In 1997, IDEA was modified to strengthen requirements for properly integrating students with disabilities. The IEPs must more clearly relate to the general-education curriculum, children with disabilities must be included in most state and local assessments, such as high school exit exams and regular progress reports must be made to parents. All public schools in the U.S. are responsible for the costs of providing a Free Appropriate Public Education as required by federal law. Mainstreaming or inclusion in the regular education classrooms, with supplementary aids and services if needed, are now the preferred placement for all children. Children with disabilities may be placed in a more restricted environment only if the nature or severity of the disability makes it impossible to provide an appropriate education in the regular classroom. Wikipedia

ONLINE EDUCATION FOR THE DISABLED

Online education has changed the way people pursue high school and higher education degrees. For many, the online venue suits the need for flexibility and a lower-cost education. For disabled students, the benefits are even greater. Although not perfect, online classrooms are free from many of the roadblocks disabled students face in traditional educational setting.

ADA

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requires schools to ensure access to an education to students with disabilities. The law includes online schools. By law, online schools must make accommodations for disabled students. These accommodations include providing lessons in formats the student can use; allowing more time to complete classwork if necessary; and altering communication or test methods when needed.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requires schools to ensure access to an education to students with disabilities. The law includes online schools. By law, online schools must make accommodations for disabled students. These accommodations include providing lessons in formats the student can use; allowing more time to complete classwork if necessary; and altering communication or test methods when needed.

Benefits

Disabled students who have a difficult time navigating brick and mortar schools often benefit from online education. Online education is far less strenuous for students bound to a wheelchair or who have mobility problems. Many online schools provide anytime, anywhere access to course materials so students are not pressed by time restrictions. Some online schools offer self-paced courses, so students feel less pressure. Disabled students who are disfigured may feel more comfortable in an online learning environment. According to Scott Stevens, who has muscular dystrophy, one of the greatest benefits is that no one knew he was disabled. Stevens now teaches in an online environment.

The use of assistive technology (AT) provides many disabled students with a way to participate in online classes. Online classes require a computer and access to the Internet. Disabled students who cannot use their hands can make use of voice-recognition software and other AT technology to access course material. Online readers, translation software, switches, specialized keyboards and other AT devices allow students with a variety of disabilities to access the same course materials as other students.

Career Choice

The number of universities offering online courses greatly expands the educational opportunities for disabled individuals. Today, disabled students can earn their associates or their master’s degrees online. Some universities offer doctorate programs as well. Some career choices allow the disabled individual to work from home after the degree is earned. Degreesandtraining.com lists five top career choices for disabled students: computers and computer science, legal, nursing, design and management. Online courses are offered in each of these fields.

The number of universities offering online courses greatly expands the educational opportunities for disabled individuals. Today, disabled students can earn their associates or their master’s degrees online. Some universities offer doctorate programs as well. Some career choices allow the disabled individual to work from home after the degree is earned. Degreesandtraining.com lists five top career choices for disabled students: computers and computer science, legal, nursing, design and management. Online courses are offered in each of these fields.

School Selection

Not all online schools are equal when it comes to ease of access and support. Some online formats are more user-friendly than others. Disabled students should select schools that offer the most benefits in terms of their particular disability. For example, disabled students who rely on screen readers will have difficulty with online classes that use scrolling text. People with hearing disabilities will have a hard time in online classrooms that do not support captioning. Online classrooms that use specialized technology or that move at a rapid pace make it difficult to use AT equipment. Before selecting a school students should request information regarding how the school uses online technology. The student should also ask into special accommodations if the school of their choice does not offer a workable format. ehow.com

schools that offer the most benefits in terms of their particular disability. For example, disabled students who rely on screen readers will have difficulty with online classes that use scrolling text. People with hearing disabilities will have a hard time in online classrooms that do not support captioning. Online classrooms that use specialized technology or that move at a rapid pace make it difficult to use AT equipment. Before selecting a school students should request information regarding how the school uses online technology. The student should also ask into special accommodations if the school of their choice does not offer a workable format. ehow.com

Recent Comments