Teaching Articles

HOPE AND ANXIETY: WHAT DO TEACHERS THINK ABOUT THE COMMON CORE STANDARDS?

The Hechinger Report 2/26/2014

The more teachers get to know the controversial Common Core State Standards, the more they like them, according to a teacher survey published this week. And even as many states debate whether to stick with the standards, which lay out what students need to know in math and English based on requirements in other countries, the survey suggests that the Common Core is already being taught at most schools in the 45 states that adopted it.

Assistant Principal Tracee Murren leads ninth-grade Algebra 1 students at the Kingsborough Early College Secondary School in Brooklyn in a discussion about how to make a graph. (Photo: Sarah Garland)

The survey is one of two reports published this week that goes beyond the fights over whether to throw out or slow down Common Core to find out how local school districts and classroom teachers are dealing with the standards in their classrooms. The findings—both reports are published by staunch supporters of the Common Core—were largely positive.

But the feedback from teachers and districts also uncovers anxiety about how classrooms and students will be affected by the tougher standards. Teachers are still worried about how to help struggling students keep up, while districts that adopted the standards early have resorted to coming up with their own curricula to meet the standards because they’ve found few off-the-shelf materials that do a good job of matching Common Core.

And training teachers to be able to handle the Common Core remains a major concern. As one teacher in Washington told researchers: “I feel that my ability to be the best teacher possible for my students is critically affected by the lack of professional time to adjust the curriculum to the Common Core.”

The first report, published Tuesday by Scholastic and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (Gates is among Hechinger’s many funders), surveyed 20,000 American teachers last July about a range of topics, including the Common Core. The second report, published Wednesday by the right-leaning Fordham Institute, examines how four local school districts that launched Common Core early have fared and highlights best practices.

Here are some of the main takeaways about how teachers are reacting to Common Core from the Scholastic and Gates survey:

Half of teachers in Common Core states say they are already teaching the standards in their schools. Only 6 percent say they haven’t begun.

While the majority of teachers, 57 percent, say Common Core will be positive for most students, a third don’t think it will make a difference. Eight percent say it will be negative.

Elementary school teachers have a sunnier outlook on the standards than middle and high school teachers. Among high school teachers, just 41 percent think the new standards will have a positive effect.

The survey asked teachers about whether the standards will meet the goals set for them, including better preparing students for careers and to compete in a global economy. The views were mixed:

An overwhelming majority of teachers say the standards will help with consistency and clarity about what students are expected to learn across states. But just half agreed that they’ll help students prepare for careers and to compete globally.

For teachers that have already started working on the standards, 62 percent say it’s going well while 20 percent say it’s not going well.

At the same time, 75 percent of teachers say they feel prepared for the standards.

Forty percent of teachers say they worried about how students who are below grade level will keep up with the new standards, though, and more than a quarter worry about their special education students.

What to do about the lingering worries? The Fordham report highlighted best practices being used by the early adopters of the Common Core that might be helpful for others who are further behind. (The districts were Nashville, Tenn.; District 54 in Shaumburg, Ill.; in the Chicago suburbs, Kenton County School District in Northern Kentucky, and Washoe County School District in Nevada, which encompasses the Reno-Tahoe area.) Here are outtakes:

Two of the districts profiled by Fordham have pushed principals to spend more time in the classroom. In the two that hadn’t encouraged principals to focus more on teaching and less on administration, the report found that “teachers and principals report that insufficient principal training on the new standards is the biggest implementation challenge.”

Educators have been disappointed about the curriculum materials produced to match Common Core.

The early-bird districts were adapting what they had in place previously or starting from scratch to create new curricula and lesson plans.

According to the report, “All four expressed caution about spending limited dollars on materials that were not truly aligned to the Common Core and are delaying at least some of their purchases until they see products that demonstrate better alignment.”

And to address the big worry of how to train teacher:

In the four districts profiled in the Fordham report, in-class coaching and joint planning time for teachers worked better than workshops. “Teachers in these districts use their time to focus relentlessly on instruction and the Common Core—not on administrative obligations,” the report said.

The four districts didn’t have all the answers for making the transition to Common Core a smooth one, though. As one Nashville educator put it, “All our teachers feel like they’re first-year teachers right now.”

THE GRAYING OF TEACHERS

By KERRY BENEFIELD THE PRESS DEMOCRAT – 12/19/2013

Sonoma County’s workforce is aging at an unprecedented rate, and teachers are at the fore with the largest concentration of older workers of any occupation. More than one-third of the county’s educators are 55 or older and age-eligible to retire, well ahead of real estate, health care and social assistance, according to a 2013 economic indicators report from the Sonoma County Development Board.

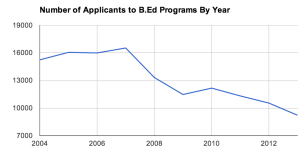

The wave of potential retirements comes at the same time that colleges and universities are turning out significantly fewer teacher candidates from their initial credentialing programs. “We are just going through into uncharted waters,” said Ben Stone, executive director of the board. “I don’t think any culture in history has gone through this kind of demographic shift.” Across California, more than 30 percent of teachers are 50 to 62 years old. Slightly more than 4 percent are 63 years or older. “I do know that I have been told that if you have more than 25 percent of staff transitioning at any one particular time, that gets to be problematic,” said Wally Holbrook, superintendent of the Lake County Office of Education, where 35 percent of the teaching ranks is age-eligible to retire.”

The percentage of teachers who were age-eligible to retire in Sonoma County hit a peak last year at 37 percent. This year, the percentage dropped to 31 percent, according to Heller. That means of more than 3,780 active teachers in Sonoma County last year, approximately 1,390 were age-eligible to retire, although there are many variables within that category, including years of actual service. About 160 did retire — well above the 125 in an average year. Planning for exodus It is hard to prepare for spikes in retirements, according to district officials.

Districts often are in the dark about the number of teachers who will retire in a given year because the decision can be deeply personal for some and can cause job insecurity for others, said Molly McGee Hewitt, executive director of the California Association of School Business Officials. “You keep a running account of your employees, but it’s hard,” she said. “A lot of people are afraid to declare, ‘If I say I’m going to retire, is it going to affect me here?”

The natural surge of baby-boomer teachers approaching retirement has been exacerbated by an economy that hit the skids in the 2007-08 school years, causing deep budget cuts, shorter school years and prompting many teachers to hit pause on their post-classroom plans. “When the economy got really difficult, people who were planning to retire stopped retiring,” McGee Hewitt said. In Petaluma City Schools, Sonoma County’s second-largest district, officials have in the past used retirement incentives to attempt to manage the percentage of teachers who leave every year, Superintendent Steve Bolman said. But numbers can remain unpredictable for a variety of reasons, he said. “You can’t control that necessarily as a district because you hire teachers as you need them and they become tenured teachers, and good teachers serving your district,” he said. “The one way you can control it on occasion is with incentives.”

As California’s school districts try to weather budget cuts managing retirements also means being able to better manage the threat of layoffs for newer teachers. “We have thrown that out there to keep our good, young teachers, to keep away from layoffs,” Bolman said of occasional retirement bonuses. With the economy largely on the mend, those teachers who did hold off on retirement now are reconsidering their options in many places.

For veteran teacher Jake Fitzpatrick, 63, the decision was largely practical, but the fallout is more emotional. The Santa Rosa High School science and physical education teacher has spent nearly 38 years in the classroom and was first tempted to consider retirement in 2009 when Santa Rosa City Schools offered a rare retirement incentive. But staying in the classroom another few years means for Fitzpatrick an additional $1,500 a month in retirement benefits. And leaving midyear — his last day is Friday — allows him to return to the classroom in 2014-15 after a state-mandated waiting period should he choose to substitute teach or coach. “I’m going to have a nice retirement because I have so many years in the system,” he said.

For veteran teacher Jake Fitzpatrick, 63, the decision was largely practical, but the fallout is more emotional. The Santa Rosa High School science and physical education teacher has spent nearly 38 years in the classroom and was first tempted to consider retirement in 2009 when Santa Rosa City Schools offered a rare retirement incentive. But staying in the classroom another few years means for Fitzpatrick an additional $1,500 a month in retirement benefits. And leaving midyear — his last day is Friday — allows him to return to the classroom in 2014-15 after a state-mandated waiting period should he choose to substitute teach or coach. “I’m going to have a nice retirement because I have so many years in the system,” he said.

In Mendocino County, the surge of retirements began affecting personnel ranks three years ago, said county Superintendent Paul Tichinin, “and will continue probably, steadily for another three to five years,” he said.

“Fort Bragg . . . in the last three years they have hired 25 new teachers. That is over 10 percent,” Tichinin said. The trend has school officials looking for younger teachers to join the ranks, but the number of teachers available has fallen off in recent years, said Sonoma County’s Heller. “I think fewer and fewer students are going into that field,” he said. “We are seeing that throughout the state of California — there is not as much enrollment in the education programs.”

The number of teacher candidates who completed the requirements for initial teaching credentials fell 32 percent between 2007-08 and 2011-12, according to the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. “It’s something we are watching and keeping our eye on,” said Karen Ricketts, regional director of the North Coast region’s beginning teacher program. Budget cuts and high-profile layoffs of less senior teachers can scare off potential teachers, said Andy Brennan, president of the Santa Rosa Teachers Association. “It has lots to do with the recession — they were laying off teachers by droves,” he said. “In general, those are the less senior teachers, so a lot of people got discouraged and went into another field.”

Stone, of the Economic Development Board, said the numbers show an opportunity for young professionals as well as professional development programs to foster teaching as a career. “If you want to be a teacher, there has been no better time since 1946 to be teacher,” he said. “There is going to be a demand.”

For Fitzpatrick, retirement brings conflicting emotions. He offered old science exams, lesson plans and other materials to colleagues, but much of it went untouched. He put it in the recycle bin. “That was hard, that was hard,” he said. “You think, ‘There goes a career.’ ” “It’s not like construction, where you can pour the concrete and build the building and go back and say, ‘Hey, I built that,’ ” he said. “It’s in the minds and hearts of the kids you worked with over the years. Hopefully, some of them are better for it.

FEWER YOUNG PEOPLE BECOMING TEACHERS; SCHOOLS COULD BE SHORT-STAFFED IN YEARS AHEAD

Jennifer M. Howell/News-Sentinel

Posted: Monday, February 7, 2011

By Jennifer Bonnett

Ever since she was a little girl, Chelsey Ligocki has wanted to be a teacher. The 2009 Lodi High School graduate is not swayed by the budget cuts hitting education or the possibility she might be laid off when she finds that perfect job after graduation. Apparently she’s in the minority. A number of recent reports paint a cautious picture of the future of teaching.

Baby Boomers are retiring, and college students appear hesitant to step into those roles due to decreasing salaries, increasing layoffs and a less-than-welcoming teaching atmosphere. And, with student enrollment expected to begin to rise again, some predict there could be a teacher shortage in the next few years. “Shortage is a distinct possibility,” said George Neely, Lodi Unified School District board president and a former teacher. “The declining enrollment in teacher certification programs and certificates issued over the last few years is a clear flag that districts may face a completely opposite problem from our current situation in the near future.”

A study that the Center for the Future of Teaching and Learning (CFTL) in Santa Cruz released last month concludes there are fewer teachers to educate an increasing student population, and that fewer people are entering the profession. The study also finds that those who are staying face much tougher economic conditions than a decade ago. Together, these elements are posing a danger to the future of education in California, the study concludes. From 2008 to 2010, the number of teachers in California declined about 10,600 to the lowest total number in the career field in a decade, according to the CFTL. First and second-year teachers declined by 50 percent in the same period.

An Aging Workforce

In 2005-06, researchers from the U.S. Department of Education looked at the average California teacher’s age and found a large number in their late 50s. Figures for Lodi Unified are unavailable. But in Galt, the average age for elementary educators is 44. The typical retirement age is 63, according to the district’s personnel department.

In a typical year, 40 teachers retire from the Lodi district. Last spring, however, exactly 100 subscribed to an early retirement program that was believed to save the district money and provide jobs for previously laid-off teachers. Roughly six dozen were re-employed.

Former teacher Susan Heberle is among those who took advantage of the incentive and is not surprised by the statewide teacher shortage projections. However, she wonders how it will affect students. When she went to college in the 1970s, there were few career paths other than teaching and nursing open to women. After graduation, she went to work at Tokay High School and remained there for 31 years. Her husband, Ron, was recently elected to the school board.

Former teacher Susan Heberle is among those who took advantage of the incentive and is not surprised by the statewide teacher shortage projections. However, she wonders how it will affect students. When she went to college in the 1970s, there were few career paths other than teaching and nursing open to women. After graduation, she went to work at Tokay High School and remained there for 31 years. Her husband, Ron, was recently elected to the school board.

For years, Heberle said, the average age of the teachers in the Tokay science department, where she taught, was 50. With recent Baby Boomer-age retirements, it has shifted and most teachers are in their 30s, thus bucking the belief, at least locally, that no one will fill the void left by retirees.

“It’s good when you have teachers who know the ropes along with the new ones coming in. When you get that nice mix of people, students benefit,” she said, adding that the district has seen a lot of retirements over the last five years. “Those teachers provided stability. They lived in Lodi and had been at the same schools for years.”

Local teacher demand high

In 2008 — even before teacher furlough days and shortening the school year became common — the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences conducted a report on the trends of teacher demand. Based on expected teacher retirements and student enrollment growth, analysis suggested that the Central Valley will face some of the highest demand for new teachers in the coming decade, mostly due to current teachers’ ages and an influx of students.

Sacramento County schools could need even more teachers because of the region’s size, the report said. It is one of 10 counties in California that account for more than 70 percent of the state’s student enrollment, and will drive much of the state’s enrollment and retirement-related teacher demand over the coming decade, the report predicted. This means that Sacramento will need to hire close to 7,000 teachers before 2015 to replace roughly 60 percent of the 2005 workforce.

Karen Schauer, superintendent of Galt Joint Union Elementary School District, believes that the less-veteran teachers there will be able to fill the retirement void there should trustees decide to  eliminate class-size reduction in the youngest grades. “When enrollment significantly increases in our district again, we will need new teachers,” she said.

eliminate class-size reduction in the youngest grades. “When enrollment significantly increases in our district again, we will need new teachers,” she said.

Whether it’s the economy or the age of the current workforce, University of the Pacific professor Lynn Beck also believes there will be a teacher shortage in the coming years. “We know excellent teachers are the key to students learning at high levels. We also know that work conditions, support, et cetera are actually more important to teachers than high salaries,” she said.

In his role as a board trustee, Neely, too, is concerned with retention and creating what he termed “job satisfaction” in the district. “I want our teachers to feel like a part of what is going on,” he said, adding that a lot of the district’s educators with the most seniority have not been listened to. On average, Lodi Unified teachers have been teaching for 13 years, the same as the state average, according to the state Department of Education.

Neely, however, had already served in the military and had a successful sales career before he decided to earn his credential in January 2006. Today, he admits he slipped into the field just before the economic issues hit. Job fairs were still commonplace and, he said last week, the internal concerns of whether he’d get a job after graduating was unwarranted. The same year, he landed a job at Lakewood Elementary School in Lodi, where he grew up and was residing.

Locally, the San Joaquin County Office of Education processed half as many credential applications for the 2009-10 school year than the previous year. The figures reflect only the credentials processed by the county Office of Education. Other processing agencies include colleges, universities and local school districts. Statewide, fewer preliminary credentials were issued in 2009, down 36 percent from 2002, according to figures from the Center for the Future of Teaching of Learning.

Building future teachers

In the past two years, there were an estimated 10,000 fewer teachers in California, according to the Center for the Future of Teaching and Learning report. Much of that is likely attributed to layoffs.

The number of new teachers, too, drastically declined. Researchers found that first and second-year teachers in this state declined by 50 percent, likely coupled with the fact that fewer college students are studying to become teachers. (Roughly 13 percent of Lodi Unified’s teachers are first and second year educators, the U.S. Department of Education reported last year).

“There’re a lot of people locally who would be great teachers, who leave in the first and second years because of working conditions,” Heberle said, ticking off a list of requirements imposed on educators by mandates under No Child Left Behind, such as rigorous benchmark testing that she feels adds extra burden to teachers. But Beck thinks the economy is the culprit. “Layoffs in many districts put many experienced teachers out of the classrooms where they had worked,” she said.

“There’re a lot of people locally who would be great teachers, who leave in the first and second years because of working conditions,” Heberle said, ticking off a list of requirements imposed on educators by mandates under No Child Left Behind, such as rigorous benchmark testing that she feels adds extra burden to teachers. But Beck thinks the economy is the culprit. “Layoffs in many districts put many experienced teachers out of the classrooms where they had worked,” she said.

Schauer agrees that college students may not be going into teaching because of the job market opportunities.” For example, health care is more promising in the job market upon college graduation than teaching at this time,” she said. Between 2002 and 2008, the number of enrollees in teacher preparation programs dropped from more than 75,000 to fewer than 45,000, the center’s report found.

However, at University of the Pacific’s Benerd School of Education, where Beck teaches prospective educators, the number of people seeking teacher credentials is actually increasing, but she said that might be because the program is so small. The age of its enrollees vary as many are looking for career changes, and some are of traditional college age. “The people who are coming to us seem to be aware of the challenges of teaching but also its importance,” she said, adding that many recent graduates have been hired. “We’re trying to make sure that they have more than one credential and have knowledge and skills that makes them both attractive to districts and competitive in the job market.”

Despite the economic climate, programs like Lodi High’s Apple Academy are still going strong. It encourages students to consider careers with children, including teaching. Now is the prime time for a teenager to consider a teaching career, said academy co-teacher Jeff Palmquist. “By the time they are able to enter it, the field should be wide open,” he said. The key will be finding people who will get excited about teaching and see its importance, Beck said, adding that Pacific’s program is built around real-world, fieldwork experience.

Schauer believes school districts can plant future teacher seeds through efforts that expose youths to tutoring and mentoring. For example, Galt High School students visit elementary schools through a child development course that gives them school tutoring experiences with younger students.

Ligocki is completing her general education at San Joaquin Delta College, with plans to transfer to Pacific. She is among a group of local students who love children and want more than money — for them to have good teachers. She has been working at the Lodi Day Nursery School for the last six months. “I hope that the cuts don’t affect me getting a job in the future when I graduate college,” Ligocki said. “I will just keep my fingers crossed that the economy will be better by the time I get out of school.”

In the end, Greer Elementary School Principal Emily Peckham and Marengo Ranch Elementary School Principal Terry Metzger said large numbers of students continue to convey on their future dream-boards that they would like to become teachers when they grow up. Palmquist agrees. “Some students have felt compelled to be a teacher from the time they started preschool,” he said.

Recent Comments