Collective Intelligence: Online Democracy or a Digital Wasteland?

Abstract from Dr. Maryanne Berry’s EDCT 552 Educational Technology Praxis Course

Wikipedia and Crowdsourcing are what Henry Jenkins calls “Collective Intelligence” in his MacArthur Foundation report “Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century,” about the participatory culture of today’s youth. Collective intelligence is “the ability to pool knowledge and compare notes with others toward a common goal.” These two phenomena represent how the democratization of the internet has changed the way content and information are created and distributed. Now anyone can create and/or edit existing content regardless of their qualifications. The central question is, “Is this a good thing that improves the human condition or are we being “dumbed down” by a tsunami of unvetted diatribe?”

“Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century,” about the participatory culture of today’s youth. Collective intelligence is “the ability to pool knowledge and compare notes with others toward a common goal.” These two phenomena represent how the democratization of the internet has changed the way content and information are created and distributed. Now anyone can create and/or edit existing content regardless of their qualifications. The central question is, “Is this a good thing that improves the human condition or are we being “dumbed down” by a tsunami of unvetted diatribe?”

As stated on their site, “Wikipedia is a free encyclopedia, written collaboratively by the people who use it. It is a special type of website designed to make collaboration easy, called a wiki. Many people are constantly improving Wikipedia, making thousands of changes per hour. All of these changes are recorded in article histories and recent changes.” They claim that because of their large contributor base from diverse backgrounds (Wikipedia has over three million posted articles) regional and cultural bias that is found in many other publications is significantly reduced which makes it very difficult for any group to censor and impose bias.

Whether it is research, tech, writing or information snippets the most important element contributors bring is a participatory culture’s willingness to help. Nobody owns articles, so if someone sees a problem that can be fixed they are encouraged to do so. Everyone is encouraged to copy-edit articles, add content and create new articles if they have knowledge of or are willing to do the necessary research to improve the subject topic. Writing in encyclopedic style with a formal tone when adding and creating new content is encouraged. Wikipedia articles should have a straightforward, just-the-facts style as opposed to essay-like, argumentative, or opinionated writing,

Whether it is research, tech, writing or information snippets the most important element contributors bring is a participatory culture’s willingness to help. Nobody owns articles, so if someone sees a problem that can be fixed they are encouraged to do so. Everyone is encouraged to copy-edit articles, add content and create new articles if they have knowledge of or are willing to do the necessary research to improve the subject topic. Writing in encyclopedic style with a formal tone when adding and creating new content is encouraged. Wikipedia articles should have a straightforward, just-the-facts style as opposed to essay-like, argumentative, or opinionated writing,

Their diverse editor base also provides access and breadth on subject matter that is otherwise inaccessible or little documented and because of this Wikipedia can produce encyclopedic articles and resources covering newsworthy events within hours or days of their occurrence. However, this also means that like any publication, Wikipedia may reflect the cultural, age, socio-economic, and other biases of its contributors. While most articles may be altered by anyone, in reality editing will be performed by a certain demographic as in younger rather than older, male rather than female, computer owner rather than those who don’t, and therefore show some bias. Wikipedia is written largely by amateurs and those with expert credentials are given no additional consideration.

Vandalism is usually easily spotted and quickly fixed and posts are more susceptible to sneaky viewpoint promotions than would be by a typical reference work. That said, bias that would not be confronted in a traditional reference work is likely to be eventually challenged. Censorship or imposing “official” points of view is extremely difficult to achieve and usually fails.

Content added to Wikipedia is never deleted as the software that runs Wikipedia retains a history of all edits and changes forever. Subjects that are contested can be vetted on the discussion pages. Accordingly, researchers can often find advocated viewpoints not present in the article. As with any source, all content should be checked. These debates reflect a cultural change that is happening across all sources of information including search engines and the media that can lead to “a better sense of how to evaluate information sources.”

The Wikimedia staff does not usually take a role in editorial issues, and projects are self-governing and consensus-driven. Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales occasionally acts as a final arbiter on the English Wikipedia. Wikipedia is transparent and self-critical; controversies are debated openly and even documented within Wikipedia itself when they cross a threshold of significance.

The Wikimedia staff does not usually take a role in editorial issues, and projects are self-governing and consensus-driven. Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales occasionally acts as a final arbiter on the English Wikipedia. Wikipedia is transparent and self-critical; controversies are debated openly and even documented within Wikipedia itself when they cross a threshold of significance.

The growing movement for free knowledge that is beginning to influence science and education is a hallmark of Wikipedia. In addition, the ability on Wikipedia to hop from one article to another aids in the serendipity that is vital to creativity.

Eight sister projects to the encyclopedia are directly operated by the Wikimedia Foundation. They include; “Wiktionary” (a dictionary and thesaurus); “Wiki-source” (a library of source documents); “Wiki-media Commons” (a media repository of more than ten million images, videos, and sound files); “Wiki-books” (a collection of textbooks and manuals); “Wikiversity” (an interactive learning resource), “Wiki-news” (a citizen journalism news site); “ Wiki-quote” (a collection of quotations); and “Wiki-species” (a directory of all forms of life). All these projects are freely licensed and open to contributions, like Wikipedia itself.

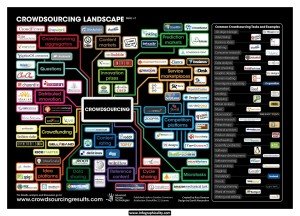

Crowdsourcing

Rather than using normal employees and/ or suppliers, “crowdsourcing” is the process of obtaining services, ideas, or content by soliciting contributions from a large group of people from an online community.The process of crowdsourcing is often used to subdivide work and combines the efforts of numerous volunteers ad/or part-time workers, where each contributor adds a small portion to the greater result.

“Crowdsourcing,” which can apply to a wide range of activities, is distinguished from “outsourcing” in that the work comes from an undefined public rather than being commissioned from a specific, named group. It can be tedious tasks split to use crowd-based outsourcing, but it can also apply to specific requests, such as “crowdfunding,” a broad-based competition, and a general search for answers, solutions, or even a missing person. “Crowdsourcing is channeling the experts’ desire to solve a problem and then freely sharing the answer with everyone.”

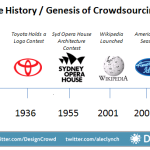

The term “crowdsourcing” was coined in 2005 by Wired Magazine editors Jeff Howe and Mark Robinson after looking at how businesses were using the Internet to outsource work to individuals. They realized that what was happening was like “outsourcing to the crowd,” which led to the term “crowdsourcing.”There are historic activities that in retrospect can be described as crowdsourcing. In the mid-19th century, The Oxford English Dictionary initiated an open call for contributions identifying all words in the English language and example quotations exemplifying their usages. They received over six million submissions over a period of 70 years. Other historic examples of crowdsourcing have been in the fields of astronomy, ornithology, mathematics and genealogy. Crowdsourcing has often been used in the past as a competition in order to discover a solution.

In the form of an “open call” crowdsourcing represents taking a function performed by employees and outsourcing it to a large, undefined network of people. It is often undertaken by individuals but can also, when the job is performed collaboratively, take the form of a peer-production. The key prerequisite is the use of the open call format and the large network of potential participants.

In the form of an “open call” crowdsourcing represents taking a function performed by employees and outsourcing it to a large, undefined network of people. It is often undertaken by individuals but can also, when the job is performed collaboratively, take the form of a peer-production. The key prerequisite is the use of the open call format and the large network of potential participants.

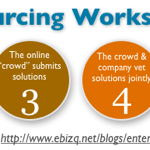

A 2008 article by Daren C. Brabham (author of the 2013 book “Crowdsourcing”) defined crowdsourcing as an “online, distributed problem-solving and production model,” in which members of the public submit solutions which are then owned by the entity which broadcast the problem.

Crowdsourcing may produce solutions from amateurs or volunteers, working in their spare time, or from experts or small businesses which were unknown to the initiating organization. In some cases, the contributors of the solution are compensated monetarily, with prizes or with recognition or in other cases, the only rewards may be kudos or intellectual satisfaction.

Entities that initiate crowdsourcing are primarily motivated by its benefits which includes the ability to gather large numbers of solutions and information at a relatively inexpensive cost while participants are motivated to get involved in crowdsourced tasks by both intrinsic motivations, such as social contact, intellectual stimulation, and passing time, and by extrinsic motivations, such as financial gain.

“Explicit crowdsourcing” lets users work together to evaluate, share and build different specific tasks, while implicit crowdsourcing means that users solve a problem as a side effect of something else they are doing. With explicit crowdsourcing, users can evaluate particular items like books or webpages, or share by posting products or items. Users can also build artifacts by providing information and editing other people’s work. “Implicit crowdsourcing” can take two forms: standalone and piggyback. Standalone allows people to solve problems as a side effect of the task they are actually doing, whereas piggyback takes users’ information from a third-party website to gather information.

Crowdsourcers

Crowdsourcing systems are used to accomplish a variety of tasks. For example, the crowd may be invited to develop a new technology, carry out a design task (also known as “community-based design” or distributed participatory design), refine or carry out the steps of an algorithm, systematize, or analyze large amounts of data. Crowdsourcing allows businesses to submit problems on which contributors can work, on topics such as science, manufacturing, biotech, and medicine, with monetary rewards for successful solutions.

Although it can be difficult to crowdsource complicated tasks, simple work tasks can be crowdsourced cheaply and effectively. Crowdsourcing also has the potential to be a problem-solving mechanism for government and nonprofit use. Urban and transit planning are prime areas for crowdsourcing. One project to test crowdsourcing’s public participation process for transit planning in Salt Lake City was carried out from 2008 to 2009, funded by a U.S. Federal Transit Administration grant. Another notable application of crowdsourcing to government problem solving is the “Peer to Patent Community Patent Review” project for the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Although it can be difficult to crowdsource complicated tasks, simple work tasks can be crowdsourced cheaply and effectively. Crowdsourcing also has the potential to be a problem-solving mechanism for government and nonprofit use. Urban and transit planning are prime areas for crowdsourcing. One project to test crowdsourcing’s public participation process for transit planning in Salt Lake City was carried out from 2008 to 2009, funded by a U.S. Federal Transit Administration grant. Another notable application of crowdsourcing to government problem solving is the “Peer to Patent Community Patent Review” project for the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Researchers have used crowdsourcing systems (in particular, the Mechanical Turk) to aid with research projects by crowdsourcing some aspects of the research process, such as data collection, parsing, and evaluation. Notable examples include using the crowd to create speech and language databases and using the crowd to conduct user studies. Crowdsourcing systems provide these researchers with the ability to gather large amount of data. Additionally, using crowdsourcing, researchers can collect data from populations and demographics they may not have had access to locally, but that improve the validity and value of their work.

Artists have also utilized crowdsourcing systems. In his project the Sheep Market, Aaron Koblin used Mechanical Turk to collect 10,000 drawings of sheep from contributors around the world. Artist Sam Brown leverages the crowd by asking visitors of his website “explodingdog” to send him sentences that he uses as inspirations for paintings. Art curator Andrea Grover argues that individuals tend to be more open in crowdsourced projects because they are not being physically judged or scrutinized. As with other crowdsourcers, artists use crowdsourcing systems to generate and collect data. The crowd also can be used to provide inspiration and to collect financial support for an artist’s work.

collect 10,000 drawings of sheep from contributors around the world. Artist Sam Brown leverages the crowd by asking visitors of his website “explodingdog” to send him sentences that he uses as inspirations for paintings. Art curator Andrea Grover argues that individuals tend to be more open in crowdsourced projects because they are not being physically judged or scrutinized. As with other crowdsourcers, artists use crowdsourcing systems to generate and collect data. The crowd also can be used to provide inspiration and to collect financial support for an artist’s work.

Additionally, crowdsourcing from 100 million drivers is being used by INRIX to collect users’ driving times to provide better GPS routing and real-time traffic updates.

Crowdsourcing and the Internet

The Internet provides a particularly good venue for crowdsourcing since individuals tend to be more open in web-based projects where they are not being physically judged or scrutinized and thus can feel more comfortable sharing. This ultimately allows for well-designed artistic projects because individuals are less conscious, or maybe even less aware, of scrutiny towards their work.

In an online atmosphere, more attention can be given to the specific needs of a project, rather than spending as much time in communication with other individuals.

Examples of Crowdsourcing

Some of these web-based crowdsourcing efforts include crowdvoting, crowdfunding, microwork, creative crowdsourcing, Crowdsource Workforce Management and inducement prize contests. Although these may not be an exhaustive list, they cover the current major ways in which people use crowds to perform tasks.

Crowdvoting

“Crowdvoting” occurs when a website gathers a large group’s opinions and judgment on a certain topic. For example, the Iowa Electronic Market is a prediction market that gathers crowds’ views on politics and tries to ensure accuracy by having participants pay money to buy and sell contracts based on political outcomes.

Crowdsourcing Creative Work

“Creative Crowdsourcing” spans sourcing creative projects such as graphic design, architecture, apparel design, writing, illustration, etc.

Crowdsourcing Language-related Data Collection

Crowdsourcing has also been used for gathering language-related data. For dictionary work, as was mentioned above, over a hundred years ago it was applied by the Oxford English Dictionary editors, using paper and postage.

Crowdsearching

Chicago-based startup “crowdfynd” utilizes a version of crowdsourcing best termed as “crowdsearching,” which differs from Microwork in that there is no obligated payment for taking part in the search. Their platform, through geographic location anchoring, builds a virtual search party of smartphone and internet users to find a lost item, pet or person, as well as return a found item, pet or property.

Crowdfunding

“Crowdfunding” is the process of funding your projects by a multitude of people contributing a small amount in order to attain a certain monetary goal. Goals may be for donations or for equity in a project. The process allows for up to 1 million dollars to be raised without a lot of the regulations being involved. The dilemma for equity crowdfunding in the U.S. is how the SEC is going to regulate the entire process.

Companies under the current proposal would have a lot of exemptions available and be able to raise capital from a larger pool of persons which can include a lot lower thresholds for investor criteria whereas the old rules required that the person be an “accredited” investor. These people are often recruited from social networks, where the funds can be acquired from an equity purchase, loan, donation, or pre-ordering.

The amounts collected have become quite high, with requests that are over a million dollars for software like Trampoline Systems, which used it to finance the commercialization of their new software. A well-known crowdfunding website Kickstarter, a website for funding creative projects, has raised over $100 million, despite its all-or-nothing model which requires one to reach the proposed monetary goal in order to acquire the money.

Macrowork

“Macrowork” tasks typically have the following characteristics: they can be done independently; they take a fixed amount of time; and that they require special skills. Macrotasks could be part of specialized projects or could be part of a large, visible project where workers pitch in wherever they have the required skills. The key distinguishing factors are that macrowork requires specialized skills and typically takes longer, while microwork requires no specialized skills.

Microwork

“Microwork” is a crowdsourcing platform where users do small tasks for which computers lack aptitude, for low amounts of money. Amazon’s popular Mechanical Turk has created many different projects for users to participate in, where each  task requires very little time and offers a very small amount in payment. An example of a Mechanical Turk project was when users searched satellite images for a boat in order to find lost researcher Jim Gray.

task requires very little time and offers a very small amount in payment. An example of a Mechanical Turk project was when users searched satellite images for a boat in order to find lost researcher Jim Gray.

The Chinese versions of this, commonly called Witkey, are similar and include such sites as Taskcn.com and k68.cn. When choosing tasks, since only certain users “win,” users learn to submit later and pick less popular tasks in order to increase the likelihood of getting their work chosen.

Inducement Prize Contests

Web-based idea competitions or inducement prize contests often consist of generic ideas, cash prizes, and an Internet-based platform to facilitate easy idea generation and discussion. An example of these competitions includes an event like IBM’s 2006 “Innovation Jam,” attended by over 140,000 international participants and yielding around 46,000 ideas.

Another example is the Netflix Prize in 2009. The idea was to ask the crowd to come up with a recommendation algorithm as more accurate than Netflix’s own algorithm. It had a grand prize of $1,000,000, and was won by the “BellKor’s Pragmatic Chaos” team which bested Netflix’s own algorithm for predicting ratings, by 10.06%.

Another example of competition-based crowdsourcing is the 2009 DARPA balloon experiment, where DARPA placed 10 balloon markers across the United States and challenged teams to compete to be the first to report the location of all the balloons. A collaboration of efforts was required to complete the challenge quickly and in addition to the competitive motivation of the contest as a whole, the winning team (MIT, in less than nine hours) established its own “collaborapetitive” environment to generate participation in their team.

Open Innovation Platforms

“Open innovation platforms” are a very effective way of crowdsourcing people’s thoughts and ideas to do research and development. The company InnoCentive is a crowdsourcing platform for corporate research and development where difficult scientific problems are posted for crowds of solvers to discover the answer and win a cash prize, which can range from $10,000 to $100,000 per challenge. They are the leader in providing access to millions of scientific and technical experts from around the world.

The company has provided expert crowdsourcing to international Fortune 1000 companies in the US and Europe as well as government agencies and nonprofits and claims a success rate of 50% in providing successful solutions to previously unsolved scientific and technical problems.

“IdeaConnection.com” challenges people to come up with new inventions and innovations and Ninesigma.com connects clients with experts in various fields. The X PRIZE Foundation creates and runs incentive competitions where one can win between $1 million and $30 million for solving challenges.

Local Motors is another example of crowdsourcing. A community of 20,000 automotive engineers, designers and enthusiasts competes to build off-road rally trucks.

Implicit Crowdsourcing

“Implicit crowdsourcing” is less obvious because users do not necessarily know they are contributing, yet can still be very effective in completing certain tasks. Rather than users actively participating in solving a problem or providing information, implicit crowdsourcing involves users doing another task entirely where a third party gains information for another topic based on the user’s actions.

A good example of implicit crowdsourcing is the ESP game, where users guess what images are and then these labels are used to tag Google images. Another popular use of implicit crowdsourcing is through reCAPTCHA, which asks people to solve CAPTCHAs to prove they are human, and then provides CAPTCHAs from old books that cannot be deciphered by computers, to digitize them for the web. Like many tasks solved using the Mechanical Turk, CAPTCHAs are simple for humans but often very difficult for computers.

Piggyback Crowdsourcing

“Piggyback crowdsourcing” can be seen most frequently by websites such as Google that data-mine a user’s search history and websites in order to discover keywords for ads, spelling corrections, and finding synonyms. In this way, users are unintentionally helping to modify existing systems, such as Google’s AdWords.

Crowdsourcing Demographics

The crowd is an umbrella term for the people who contribute to crowdsourcing efforts. Though it is sometimes difficult to gather data about the demographics of the crowd, a study by Ross et al. surveyed the demographics of a sample of the more than 400,000 registered crowdworkers using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to complete tasks for pay.

While a previous study in 2008 by Ipeirotis found that users at that time were primarily American, young, female, and well-educated, with 40% having incomes >$40,000/yr, in 2009 Ross found a very different population. By Nov. 2009, 36% of the surveyed Mechanical Turk workforce was Indian. Two-thirds of Indian workers were male, and 66% had at least a Bachelor’s degree. Two-thirds had annual incomes less than $10,000/yr, with 27% sometimes or always depending on income from Mechanical Turk to make ends meet.

The average U.S. user of Mechanical Turk earned $2.30 per hour for tasks in 2009, versus $1.58 for the average Indian worker. While the majority of users worked less than five hours per week, 18% worked 15 hours per week or more. This is less than minimum wage in either country, which Ross suggests raises ethical questions for researchers who use crowdsourcing. The demographics of http://microworkers.com/ differ from Mechanical Turk in that the U.S. and India together account for only 25% of workers.

197 countries are represented among users, with Indonesia (18%) and Bangladesh (17%) contributing the largest share. However, 28% of employers are from the U.S. Another study of the demographics of the crowd at “iStockphoto” found a crowd that was largely white, middle- to upper-class, higher educated, worked in a so-called “white collar job” and had a high-speed Internet connection at home.

Studies have also found that crowds are not simply collections of amateurs or hobbyists. Rather, crowds are often professionally trained in a discipline relevant to a given crowdsourcing task and sometimes hold advanced degrees and many years of experience in the profession. Claiming that crowds are amateurs, rather than professionals, is both factually untrue and may lead to marginalization of crowd labor rights.

G. D. Saxton et al. (2013) studied the role of community users, among other elements, during his content analysis of 103 crowdsourcing organizations. They developed a taxonomy of nine crowdsourcing models (intermediary model, citizen media production, collaborative software development, digital goods sales, product design, peer-to-peer social financing, consumer report model, knowledge base building model, and collaborative science project model) in which to categorize the roles of community users, such as researcher, engineer, programmer, journalist, graphic designer, etc., and the products and services developed.

Motivations to Crowdsource

As mentioned above, many scholars of crowdsourcing suggest that there are both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations that cause people to contribute to crowdsourced tasks and that these factors influence different types of contributors. For example, students and people employed full-time rate Human Capital Advancement as less important than part-time workers do, while women rate Social Contact as more important than men do. Intrinsic motivations are broken down into two categories: enjoyment-based and community-based motivations.

Enjoyment-based motivations refer to motivations related to the fun and enjoyment that the contributor experiences through their participation. These motivations include: skill variety, task identity, task autonomy, direct feedback from the job, and pastime. Community-based motivations refer to motivations related to community participation, and include community identification and social contact.

Extrinsic motivations are broken down into three categories: immediate payoffs, delayed payoffs, and social motivations. Immediate payoffs, through monetary payment, are the immediately received compensations given to those who complete tasks. Delayed payoffs are benefits that can be used to generate future advantages, such as training skills and being noticed by potential employers.

Extrinsic motivations are broken down into three categories: immediate payoffs, delayed payoffs, and social motivations. Immediate payoffs, through monetary payment, are the immediately received compensations given to those who complete tasks. Delayed payoffs are benefits that can be used to generate future advantages, such as training skills and being noticed by potential employers.

Social motivations are the rewards of behaving pro-socially, such as altruistic motivations. Chandler and Kapelner found that U.S. users of the Amazon Mechanical Turk were more likely to complete a task when told they were going to “help researchers identify tumor cells,” than when they were not told the purpose of their task. However, of those who completed the task, quality of output did not depend on the framing of the task.

Another form of social motivation is prestige or status. The International Children’s Digital Library recruits volunteers to translate and review books. Because all translators receive public acknowledgment for their contributions, Kaufman and Schulz cite this as a reputation-based strategy to motivate individuals who want to be associated with institutions that have prestige.

The Amazon Mechanical Turk uses reputation as a motivator in a different sense, as a form of quality control.

Crowdworkers who frequently complete tasks in ways judged to be inadequate can be denied access to future tasks, providing motivation to produce high-quality work.

Criticisms

There are two major categories of criticisms about crowdsourcing: (1) the value and impact of the work received from the crowd, and (2) the ethical implications of low wages paid to crowdworkers. Most of these criticisms are directed towards crowdsourcing systems that provide extrinsic monetary rewards to contributors, though some apply more generally to all crowdsourcing systems.

Impact of crowdsourcing on product quality

There is susceptibility to faulty results caused by targeted, malicious work efforts.

Since crowdworkers completing micro-tasks are paid per task, there is often a financial incentive to complete tasks quickly rather than well. Verifying responses is time-consuming, and so requesters often depend on having multiple workers complete the same task to correct errors.

However, having each task completed multiple times increases time and monetary costs.

Along with adding worker redundancy, it has also been showed that estimating crowdworkers’ skills and intentions and leveraging them for inferring true responses works well, albeit with an additional computation cost.

Crowdworkers are a nonrandom sample of the population

Many researchers use crowdsourcing in order to quickly and cheaply conduct studies with larger sample sizes than would be otherwise achievable. However, due to limited access to internet, participation in low developed countries is relatively low. Participation in highly developed countries is similarly low, largely because the low amount of pay is not a strong motivation for most users in these countries.

These factors lead to a bias in the population pool towards users in medium developed countries, as deemed by the Human Development Index increasing the likelihood that a crowdsourced project will fail due to lack of monetary motivation or too few participants.

Crowdsourcing markets are not a first-in-first-out queue

Tasks that are not completed quickly may be forgotten, buried by filters and search procedures so that workers do not see them. This results in a long tail power law distribution of completion times. Additionally, low-paying research studies online have higher rates of attrition, with participants not completing the study once started. Even when tasks are completed, crowdsourcing does not always produce quality results. When Facebook began its localization program in 2008, it encountered some criticism for the low quality of its crowdsourced translations.

One of the problems of crowdsourcing products is the lack of interaction between the crowd and the client. Usually there is little information about the final desired product, and there is often very limited interaction with the final client. This can decrease the quality of product because client interaction is a vital part of the design process.

It is usually expected from a crowdsourced project to be unbiased by incorporating a large population of participants with a diverse background. However, most of the crowdsourcing works are done by people who are paid or directly benefit from the outcome (e.g. most of open source projects working on Linux).

In many other cases, the end product is the outcome of a single person’s endeavor, who creates the majority of the product, while the crowd only participates in minor details.

Ethical concerns for crowdsourcers

Because crowdworkers are considered independent contractors rather than employees, they are not guaranteed minimum wage. In practice, workers using the Amazon Mechanical Turk generally earn less than the minimum wage, with U.S. users earning an average of $2.30 per hour for tasks in 2009, and users in India earning an average of $1.58 per hour, which is below minimum wage in both countries. Some researchers who have considered using Mechanical Turk to get participants for research studies have argued that the wage conditions might be unethical.

When Facebook began its localization program in 2008, it received criticism for using free labor in crowdsourcing the translation of site guidelines. Typically, no written contracts, non-disclosure agreements, or employee agreements are made with crowdworkers. For users of the Amazon Mechanical Turk, this means that requestors decide whether users’ work is acceptable, and reserve the right to withhold pay if it does not meet their standards.

Critics claim that crowdsourcing arrangements exploit individuals in the crowd, and there has been a call for crowds to organize for their labor rights. Collaboration between crowd members can also be difficult or even discouraged, especially in the context of competitive crowd sourcing. Crowdsourcing site “InnoCentive” allows organizations to solicit solutions to scientific and technological problems; only 10.6% of respondents report working in a team on their submission.

The following is a sampling of Wikipedia’s “Crowdsourcing in Real Time.” Click on the following link to watch real time responses to crowdsourcing request from around the world. When a response comes in their location is highlighted on a map of the world. I don’t know about participation but it’s amazing to watch!

Wikipedia crowdsourcing in real time: http://rcmap.hatnote.com/#en

Someone in Killen (Alabama, United States) edited “Mike Curtis (Alabama politician)” (en)

Someone in Hamburg (Hamburg, Germany) edited “1970–71 European Cup” (en)

Someone in Rio De Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) edited “A Fazenda 7” (en)

Someone in Auburn (Alabama, United States) edited “1959 Ole Miss Rebels football team” (en)

Someone in Canada edited “Robert Campbell (curler)” (en)

Someone in Plaza (Veraguas, Panama) edited “Law enforcement in New York City” (en)

Someone in Santa Ana (California, United States) edited “Robert MacNaughton” (en)

Someone in Auburn (Alabama, United States) edited “1959 Ole Miss Rebels football team” (en)

A Cult of Amateurs

Andrew Keen is not a big fan of Collective Intelligence, not the digital kind anyway. In his book Cult of the Amateur (2007) he states “These days, kids can’t tell the difference between credible news by objective professional journalists and what they read on joeshmoe.blogspot.com. (7) For these Generation Y utopians, every posting is just another person’s version of the truth; every fiction is just another person’s version of the facts.” He continues “and instead of creating masterpieces, these millions and millions of exuberant monkeys (computer users)—many with no more talent in the creative arts than our primate cousins—are creating an endless digital forest of mediocrity.” (12)

He feels that our attitudes about “authorship,” too, are undergoing a radical change as a result of today’s democratized Internet culture and that the idea of original authorship and intellectual property has been seriously compromised. This has been compounded by the ease in which we can now cut and paste other people’s work to make it appear as if it’s ours, has resulted in a troubling new permissiveness about intellectual property.

Cutting and pasting, of course, is child’s play on the Web 2.0, enabling a younger generation of intellectual kleptomaniacs, who think their ability to cut and paste a well-phrased thought or opinion makes it their own. (23) In the words of Lawrence Leddig, Stanford law professor and creator of Creative Commons, “Today’s audience isn’t listening at all – it’s participating in the latest Web 2.0 “remixing” of content and “mashing up” of software and music. The record, not the remix, is the anomaly today. The remix is the very nature of the digital.

Kevin Kelly, in a May 2006 New York Times Magazine article, celebrates the death of the traditional stand-alone text—what centuries of civilization have known as the book. What Kelly envisions instead is an infinitely interconnected media in which all the world’s books are digitally scanned and linked together: what he calls the “liquid version” of the book. In Kelly’s view, the act of cutting and pasting and linking and annotating a text is as or more important than the writing of the book in the first place. It is the literary version of Wikipedia where we should embrace, a single, hyperlinked, communal, digital text that is edited and annotated by amateurs.

Now I wouldn’t go so far as to encourage “the death of the book” what we are seeing is an evolution of literacy. Since there is now no way to stop it we have to learn to adapt. Researchers have to “check their sources” and students have to be taught the same. If a consumer wants to read an original book or listen to an original song those items are still very much available and much more easily accessible on the internet. If someone wants to “remix” then that original work becomes and “art form.” If the adulterator makes money off the remix or “mashup” then the original author or artist should be acknowledged and compensated.

Keen goes on the lament about the fact that traditional writers, researchers and literary scholars are in danger of losing their jobs because now anyone can post anything on the internet. However, people are still looking for authenticity in their sources of literary consumption. The last time I looked Brooks, Will, Friedman and Kristof are all gainfully employed by the New York Times and the Washington Post. Writer Internships are now being done in blogs on the internet and if an up-and-coming writer is good s/he will find an audience.

A lot of what is pasted off as “academic research” in collective intelligence sites like Wikipedia is there to fill a void. There are countless scholastic dissertations and thesis locked away in the libraries of colleges and universities. As stated in Nickolas Kristof’s NY Times article “Professors, We Need You,” (http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/16/opinion/sunday/kristof-professors-we-need-you.html), “A related problem is that academics seeking tenure must encode their insights into turgid prose. As a double protection against public consumption, this gobbledygook is then sometimes hidden in obscure journals — or published by university presses whose reputations for soporifics keep readers at a distance.” If these vetted publications were made available, in readable and understandable prose, to the world collective intelligence through sources like Wikipedia it would go a long way in legitimizing open content because these sources would have already been peer reviewed.

The bottom line is that “monkey” authorship is here to stay. I would personally rather be exposed to a source that I have to verify than to not be exposed to that source at all.

Collective Intelligence in the Classroom

There is an ongoing debate on whether Wikipedia should be used as a learning tool in K-12 education. Jessica Parker, in her book “Teaching Tech-Savvy Kids: Bringing Digital Media Into the Classroom, Grades 5-12,” addresses this quandary by saying, “With some colleges banning Wikipedia, teachers are left wondering if they should do the same. The problem with this situation is that it seems to be an either-or question: Should teachers allow Wikipedia to be used as a source? This question directs the discussion toward including or excluding sources when, really, teachers should concern themselves with the quality of sources. From Wikipedia’s standpoint, questions should be, when is it better to consult a traditional encyclopedia, when is it better to consult Wikipedia, and when do we consult both? Instead of focusing on a question that could potentially exclude Wikipedia (even though we know the students will use it anyway even if we do this), we can now be critical of all sources and determine which sources will help us find answers to a specific inquiry. (76)

Parker then gives this hypothesis, “Consider the content standards for history for eleventh graders in the state of California. Standard 11.1 requires students to “analyze the significant events in the founding of the nation” and this includes “the ideological origins of the American Revolution.” As teachers, we understand that the view from an American history textbook concerning the American Revolution might vary considerably from the view of a British textbook on the same subject. Yet the English Wikipedia entry has to report both of these two perspectives. Instead of excluding Wikipedia because it is not a vetted source like a textbook, imagine if teachers helped students to understand why these two views differed.”

The matter of collective intelligence is addressed when Parker says, “Imagine a culture where information is collectively valued. The current digital era has convinced me that the trusted single source, e.g., printed encyclopedias, has given way to a multiplicity of sources. This means that students now more than ever need to understand how to interpret and evaluate information; being literate depends on it. As Paul Duguid (2007), an adjunct professor in the School of Information at U.C. Berkeley, states, “Questions of quality … are less about what single source to trust for everything than about when to trust a particular source for the question at hand.” (p. 76).

The reality is printed encyclopedias are not magic bullets presented out of thin air; they are but one “constructed” reference item to be used in conjunction with other sources. The best researchers, whether they are working on their seventh-grade assignment or their master’s thesis, have a number of resources for finding information and will switch from printed reference material to Wikipedia and other online sources to primary source documents and back again in order to find what they are looking for. The goal of a researcher is to explore possibilities, not to search for the “right” answer since the right answer depends on context (see paragraph above concerning American Revolution). (p. 77).

Now that we have unanimously (cough) agreed that the dynamics of Wikipedia and how to use it should be taught to students, the next question is how to go about it. In the book’s section IT’S TIME TO PLAY! Parker states, “Just as our students are active innovators of digital media such as Wikipedia, it is also important for us, their teachers, to see what all the fuss is about. “Wikipedia 101 is designed for newcomers to Wikipedia. Haven’t visited Wikipedia? Don’t really understand what it is? Try the simple (and not so simple) activities below. Remember to adopt the youthful mentality of play. (78)

The following activities are for you to try. All you need is access to the Internet and some good old-fashioned curiosity.

• Since Wikipedia supports collaborative knowledge, find a friend or colleague who is also curious about Wikipedia and explore the site together. It might not be beneficial to partner up with a peer who is already a Wikipedian; they might move too fast, assume too much, and even hog the mouse and keyboard. Your best bet is to find another novice such as yourself and start exploring.

• The first thing to do is find and read the about page. A majority of sites have this type of link and it can provide important contextual information in order for you to get the lay of cyberland, so to speak.

• Visit “Today’s Featured Article” on the main page: Allow yourself to get your bearings with this fun article.

• Click on “random article” and see where it takes you.

• Now you are ready to check out articles on topics you love and have taught over the years. See what is out there and see if these articles are up-to-par or if they need some additional work. Also make sure to check out their history and discussion tabs.

• If you consider yourself brave (and since you are presumably an expert in your field), go forth and edit! As Wikipedia says, “Be bold, but remember to stay cool. You are judged wholly and solely on the quality of your contributions, not on your education or profession.”

You might even find that writing Wikipedia articles is more difficult than it may first seem.

Once you have tried these activities, continue with the Expert Wikipedian section for another challenge below. (pp. 74-75). Expert Wikipedians: Are you already a Wikipedian and want to see what else is possible with a wiki? Then this section is for you. This section is designed for teachers who are familiar with Wikipedia but don’t know what to do beyond editing entries. Here are some ideas.

• User/ Designer Perspective: first, take the perspective of a user of Wikipedia and spend five minutes searching for topics, visiting the main page and the random page. Then, for the next five minutes, take the perspective of a designer of Wikipedia. Look at the layout of each wiki page: What are your eyes attracted to at first? Do you find it harder to find some links rather than others? If so, why do you think they designed it this way? If not, what about the design makes it easy for you to see the links?

• Taking both a user and a designer perspective is an important aspect of understanding digital media (and our traditional media as well). As a user, you make meaning of the site as you navigate through the pages; as a designer, you come to understand how the site was constructed with certain intentions in mind. If you plan to teach your students about Wikipedia (or any medium for that matter) these two perspectives will be essential components.

• Create an account! Although you can access Wikipedia and edit articles, you cannot start new pages without first creating an account and logging in. Logging in also allows you to rename pages, upload images, edit semi-protected pages and create a user page.

• Run out of things to edit? Check out the community portal link on the main navigation bar. It takes you to a community bulletin board which lists new project pages that are seeking contributors, a podcast called WikiVoices discussion forums, and collaborations.

• Visit Wikipedia’s sister projects: Wiktionary, Wikiversity, Wikinews, Wikibooks and Wikiquote! Also check out Wikimedia Commons, a media file repository for freely-licensed educational media content. (pp. 75-76).

Danah Boyd (2007) suggests that understanding Wikipedia means knowing how to:

1. Understand the assembly of data and information into publications

2. Interpret knowledge

3. Question purported truths and vet sources

4. Analyze apparent contradictions in facts

5. Productively contribute to the large body of collective knowledge (p 73)

For educators interested in how to teach better Web searching skills, Google for Educators (http:// www.google.com/ educators/ index.html) has put together through their Google Certified Teachers program lessons and resources on this important subject.

Lessons and resources include understanding search engines and search techniques and strategies (http:// www.google.com/ educators/ p_websearch.html (p. 78).

Source Articles

Skim Wikipedia’s page about its strengths and weaknesses:

Keen, Andrew (2007-06-05). The Cult of the Amateur: How blogs, MySpace, YouTube, and the rest of today’s user-generated media are destroying our economy, our culture, and our values (Kindle Locations 36-38). Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Recent Comments