Screencasting & Digital Storytelling

SCREENCASTING

A recent trend in eLearning is screencasting. There are many screencasting tools available but the latest one allows the users to create screencasts directly from their browser and make the video available online so that the viewers can stream the video directly. The advantage of such tools is that it gives the teacher the ability to show her ideas and flow of thoughts rather than simply explain them, which may be more confusing when delivered via simple text instructions.

available online so that the viewers can stream the video directly. The advantage of such tools is that it gives the teacher the ability to show her ideas and flow of thoughts rather than simply explain them, which may be more confusing when delivered via simple text instructions.

Research on the use of video in lessons is preliminary, but early results show an increased retention and better results when video is used in a lesson. Creating a systematic video development method holds promise for creating video models that positively impact student learning (see Blended-based Learning).

DIGITAL STORYTELLING

“Digital storytelling” (DST) refers to a short form of digital film-making that allows everyday people to share aspects of their life story. DST is a relatively new term which describes the new practice of ordinary people who use digital tools to tell their ‘story’. Digital stories often present in compelling and emotionally engaging formats, and can be interactive.

The term “digital storytelling” can also cover a range of digital narratives (web-based stories, interactive stories, hypertexts, and narrative computer games); it is sometimes used to refer to film-making in general, and as of late, it has been used to describe advertising and promotion efforts by commercial and non-profit enterprises.

One can define DST as the process by which diverse peoples share their life story and creative imaginings with others. This newer form of storytelling emerged with the advent of accessible media production techniques, hardware and software, including but not limited to digital cameras, digital voice recorders, iMovie, Windows Movie Maker and Final Cut Express. These new technologies allow individuals to share their stories over the Internet on YouTube, Vimeo, compact discs, podcasts, and other electronic distribution systems.

One can define DST as the process by which diverse peoples share their life story and creative imaginings with others. This newer form of storytelling emerged with the advent of accessible media production techniques, hardware and software, including but not limited to digital cameras, digital voice recorders, iMovie, Windows Movie Maker and Final Cut Express. These new technologies allow individuals to share their stories over the Internet on YouTube, Vimeo, compact discs, podcasts, and other electronic distribution systems.

One can think of digital storytelling as the modern extension of the ancient art of storytelling, now interwoven with digitized still and moving images and sound. Thanks to new media and digital technologies, individuals can approach storytelling from unique perspectives. Many people use elaborate non-traditional story forms, such as non-linear and interactive narratives.

Simply put, digital stories are multimedia movies that combine photographs, video, animation, sound, music, text, and often a narrative voice. Digital stories may be used as an expressive medium within the classroom to integrate subject matter with extant knowledge and skills from across the curriculum. Students can work individually or collaboratively to produce their own digital stories. Once completed, these stories are easily be uploaded to the internet and can be made available to an international audience, depending on the topic and purpose of the project.

DIGITAL STORYTELLING DEVELOPMENT AND PIONEERS

The broad definition has been used by many artists and producers to link what they do with traditions of oral storytelling and often to distinguish their work from slick or commercial projects by focusing on authorship and humanistic or emotionally provocative content. Digital Storytelling has been used by Ken Burns, in the documentary “The Civil War,” cited as one of the first models of this genre. In his documentary, Burns used first-person accounts that served to reveal the heart and emotions of this tragic event in American history, as well as narration, archival images, modern cinematography, and music (Sylvester & Greenidge, 2009). Some of the other artists who have described themselves as digital storytellers are the late Dana Atchley, his collaborator Joe Lambert, Abbe Don, Brenda Laurel, and Pedro Meyer.

The “short narrated films” definition of digital storytelling comes from a production workshop by Dana Atchley at the American Film Institute in 1993 that was adapted and refined by Joe Lambert in the mid-1990s into a method of training promoted by the San Francisco Bay Area-based Center for Digital Storytelling.

Typically, digital stories are produced in intensive workshops. The product is a short film that combines a narrated piece of personal writing, photographic and other still images, and a musical soundtrack. Technology enables those without a technical background to produce works that tell a story using “moving” images and sound. The lower processing and memory requirements for using stills as compared with video, and the ease with which the so-called “Ken Burns” pan effect can be produced with video editing software, have made it easy to create good-looking short films.

Digital storytelling was integrated into public broadcasting by BBC’s “Capture Wales” project. The following year a similar project was launched by the BBC in England titled “Telling Lives.” Sveriges Utbildnings radio created “Rum för Berättande” (“Room for Storytelling”). Netherlands Educational TV, Teleac/NOT created a program with young people in Amsterdam. KQED, Rocky Mountain PBS, WETA and other public television stations in the US have developed projects. Digital storytelling is evolving from the simple narrated video to forms that are interactive and look better. These include websites and online videos created to promote causes, entertain, educate, and inform audiences. Wikipedia

Digital storytelling was integrated into public broadcasting by BBC’s “Capture Wales” project. The following year a similar project was launched by the BBC in England titled “Telling Lives.” Sveriges Utbildnings radio created “Rum för Berättande” (“Room for Storytelling”). Netherlands Educational TV, Teleac/NOT created a program with young people in Amsterdam. KQED, Rocky Mountain PBS, WETA and other public television stations in the US have developed projects. Digital storytelling is evolving from the simple narrated video to forms that are interactive and look better. These include websites and online videos created to promote causes, entertain, educate, and inform audiences. Wikipedia

“Our findings indicate that Digital storytelling (DST) participants performed significantly better than lecture-type IT-II participants in terms of English achievement, critical thinking, and learning motivation. Interview results highlight the important educational value of DST, as both the instructor and students reported that DST increased students’ understanding of course content, willingness to explore, and ability to think critically, factors which are important in preparing students for an ever-changing 21st century.” Taiwan University – 2011

DIGITAL STORYTELLING COMPONENTS

The most important characteristics of a digital story are that it no longer conforms to the traditional conventions of storytelling because it is capable of combining still imagery, moving imagery, sound, and text, as well as being nonlinear and contain interactive features. The expressive capabilities of technology offer a broad base from which to integrate. It enhances the experience for both the author and audience and allows for greater interactivity.

With the arrival of new media devices like computers, digital cameras, recorders, and software, individuals may share their digital stories via the Internet, on discs, podcasts, or other electronic media. Digital storytelling combines the art of storytelling with multimedia features such as photography, animation, text, audio, voiceover, hypertext, and video. Digital tools and software make it easy and convenient to create a digital story. Common software includes iMovie and Movie Maker for user-friendly options. There are other online options and free applications as well.

Educators often identify the benefit of digital storytelling as the array of technical tools from which students may select for their creative expression. Learners set out to use these tools in new ways to make meaningful content. Students learn new software, choose images, edit video, make voiceover narration, add music, create title screens, and control flow and transitions. Additionally, there is opportunity to insert interactive features for “reader” participation. It is possible to click on imagery or text in order to choose what-will-happen next, cause an event to occur, or navigate to online content.

make meaningful content. Students learn new software, choose images, edit video, make voiceover narration, add music, create title screens, and control flow and transitions. Additionally, there is opportunity to insert interactive features for “reader” participation. It is possible to click on imagery or text in order to choose what-will-happen next, cause an event to occur, or navigate to online content.

Additionally, distinctions may be drawn between “Web 2.0 storytelling” and that of digital storytelling. Web 2.0 storytelling is said to produce a network of connections via social networking, blogging, and YouTube that transcends beyond the traditional, singular flow of digital storytelling. It tends to “aggregate large amounts of microcontent and creatively select patterns out of an almost unfathomable volume of information,” therefore the bounds of Web 2.0 storytelling are not necessarily clear.

Another form of digital storytelling is the micromovie, which is “a very short exposition lasting from a few seconds to no more than 5 minutes in length. It allows the teller to combine personal writing, photographic images or video footage, narrative, sound effects, and music. Many people, regardless of skill level, are able to tell their stories through image and sound and share those stories with others.

DIGITAL STORYTELLING USES IN EDUCATION

The Center for Digital Storytelling model has also been adopted in education, especially in the US, sometimes as a method of building engagement and multimedia literacy. For example, the Bay Area Video Coalition and Youthworx Media Melbourne employ digital storytelling to engage and empower young people at risk.

Uses in Primary and Secondary Education

The idea of merging traditional storytelling with today’s digital tools is spreading worldwide. Anybody today with a computer can create a digital story simply by answering such questions as:

- What do you think?

- What do you feel?

- What is important?

- How do we find meaning in our lives?

Most digital stories focus on a specific topic and contain a particular point of view. These topics can range from personal tales to the recounting of historical events, from exploring life in one’s own community to the search for life in other corners of the universe and every story in between.

For primary grades the focus is related to what is being taught, a story that will relate to the students. For primary grades the story is kept under five minutes to retain attention. Vibrant pictures, age-appropriate music and narration are needed. Narration accompanied by subtitles can also help build vocabulary. Content-related digital stories can help upper-elementary and middle-school students understand abstract or layered concepts.

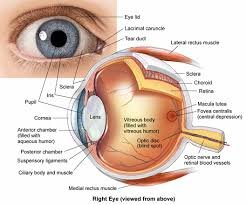

For example, in one 5th grade class a teacher used digital storytelling to depict the anatomy of the eye and describe its relationship to a camera. A fifth grader said, “This year I have learned that places are not just physical matter but emotional places in peoples’ hearts. iMovie has made all my thoughts and feelings come alive in an awesome movie.”

These aspects of digital storytelling, pictures, music, and narration reinforce ideas and appeal to different learning types. Teachers can use it to introduce projects, themes, or any content area, and can also let their students make their own digital stories and then share them. Teachers can create digital stories to help facilitate class discussions, as an anticipatory set for a new topic, or to help students gain a better understanding of more abstract concepts.

These stories can become an integral part of any lesson in many subject areas. Students can also create their own digital stories and the benefits that they can receive from it can be quite plentiful. Through the creation of these stories students are required to take ownership of the material they are presenting (see: Blended-based Learning). They have to analyze and synthesize information as well. All of this supports higher level thinking. Students are able to give themselves a voice through expressing their own thoughts and ideas.

Software such as iMovie, Photo Story 3, or Movie Maker do all that is required. Faculty and graduate students at the University of Houston have created a website, The Educational Use of Digital Story Telling, which focuses on the use of digital storytelling by teachers and their students across multiple content areas and grade levels.

The National Writing Project has a collaboration with the Pearson Foundation examining the literacy practicesinvolved in their digital storytelling work with students.

DIGITAL STORYTELLING USE BY TEACHERS IN CURRICULUM

Teachers can incorporate digital storytelling into their instruction for several reasons. Two reasons include:

1) to incorporate multimedia into their curriculum

2) Teachers can also introduce storytelling in combination with social networking in order to increase global participation, collaboration, and communication skills.

Moreover, digital storytelling is a way to incorpor ate and teach the twenty-first century student the twenty-first century technology skills such as information literacy, visual literacy, global awareness, communication and technology literacy.

ate and teach the twenty-first century student the twenty-first century technology skills such as information literacy, visual literacy, global awareness, communication and technology literacy.

A handful of teachers around the world have embraced digital storytelling from a mobile platform. The use of small handheld devices allows teachers and students to create short digital stories without the need for expensive editing software. iOS devices are the norm nowadays and mobile digital storytelling applications like Storyrobe have introduced an entirely new set of tools for the classroom.

With an emphasis on collaborative learning and hands on teaching, this website offer an in depth look at how to integrate 21st Century Skills with the objectives of a rigorous academic program: http://nafcollaberationnetwork.org/curriculum-instruction/ci-pbl-ds.html

DIGITAL STORYTELLING USES IN HIGHER EDUCATION

Digital storytelling spread in higher education in the late nineties with the Center for Digital Storytelling (CDS) collaborating with a number of Universities while based at UC Berkeley. CDS programs with the New Media Consortium led to links to many campuses where programs in digital storytelling have grown; these include University of Maryland Baltimore, Cal State Monterey, Ohio State University, Williams College, MIT, and the University of Wisconsin, Madison. The University of Colorado, Denver, Kean University, Virginia Tech, Simmons College, Swarthmore College, the University of Calgary, University of Massachusetts (Amherst), the Maricopa County Community Colleges (AZ), and others have developed programs. The University of Utah offered its first class on digital storytelling (Writing 3040) in the fall of 2010. The program has grown from 10 students the first semester to over 30 in 2011, including 5 graduate students.

The distribution of digital storytelling among humanities faculty connected with the American Studies Crossroads Project was a further evolution through a combination of both personal and academic storytelling. Starting in 2001, Rina Benmayor (from California State University-Monterey Bay) hosted a Center for Digital Storytelling seminar and began using digital storytelling in her Latino/a life stories classes. Benmayor began sharing that work with faculty across the country involved in the Visible Knowledge Project including Georgetown University; LaGuardia Community College, CUNY; Millersville University; Vanderbilt University, and University of Wisconsin–Stout. Out of this work emerged publications in several key academic journals as well as the Digital Storytelling Multimedia Archive.

Latino/a life stories classes. Benmayor began sharing that work with faculty across the country involved in the Visible Knowledge Project including Georgetown University; LaGuardia Community College, CUNY; Millersville University; Vanderbilt University, and University of Wisconsin–Stout. Out of this work emerged publications in several key academic journals as well as the Digital Storytelling Multimedia Archive.

Ball State University has a master’s program in digital storytelling based in the Telecommunications Department, as does the University of Oslo. In 2011, the University of Mary Washington launched an open online course in digital storytelling titled “DS106.” The course includes credit-seeking students at the University as well as many open, online participants from around the world. Digital storytelling is also used as an instructional strategy to not only build relationships and establish people’s social presence online but also as an alternative format to present content. Wikipedia

Recent Comments