Education Game-based eLearning

OVERVIEW

Computer gaming is big business. According to Robert Lee Hotz’s 3/15/12 WSJ article When Gaming Is Good for You (see article below) computer gaming, “has become a $25 billion-a year entertainment business behemoth since the first coin-operated commercial videogames hit the market 41 years ago. In 2010, gaming companies sold 257 million video and computer games, according to figures compiled by the industry’s trade group, the Entertainment Software Association.”

A growing body of university research suggests that gaming improves creativity, decision-making and perception. The specific benefits are wide ranging, from improved hand-eye coordination to vision changes that boost night driving ability. People who played action-based video and computer games made decisions 25% faster than others without sacrificing accuracy and the most adept gamers can make choices and act on them up to six times a second—four times faster than most people.

Multi-tasking is also enhanced as experienced game players can pay attention to more than six things at once without getting confused compared with the four that someone can normally keep in mind. Other findings found that women—who make up about 42% of computer and videogame players—were better able to mentally manipulate 3D objects, a skill at which men are generally more adept. Most studies looked at adults rather than children and the studies were conducted independently of the companies that sell video and computer games.

Electronic gameplay also has its downside as brain scans show that violent videogames can alter brain function in healthy young men after just a week of play, depressing activity among regions associated with emotional control. Other studies have found an association between compulsive gaming and being overweight, introverted and prone to depression. The studies didn’t compare the benefits of gaming with such downsides.

The violent action games that often worry parents most had the strongest beneficial effect on the brain which one would not think are mind-enhancing. As it happens all the games that have the good learning effect happen to be violent but it is not known whether the violence is important or not. Researchers hope not but have yet to create educational software as engaging as most action games.

As the research goes on one thing is certain computer educational games are here to stay. As studies show computer educational games video games are be a great way to bring a new form of learning into the classroom. When someone plays a video game, they are challenged mentally with a problem. Through playing they will discover many different ways to solve problems they will come across.

In good games, they will often find that they will require these skills later on in the game as well, and thus be required to maintain and hone their skills for later on. Video games also often provide instant rewards for succeeding in solving a problem. This is in contrast to the classroom where students wait for graded tests and are only rewarded occasionally with report cards to report their progress. Video games can instantly tell a student of failure or success and often this can be used to develop skills along the way.

HISTORY OF EDUCATIONAL GAMES

Playing games is a natural and universal human activity. For millennia, games have inspired and motivated active learning. They encourage collaboration, offer performance challenges, compel adaptation to diverse situations, leverage and reward practice, and engage players for a lifetime. Games for a Digital Age.

Gaming has been used in educational circles since at least the 1900s. Use of paper-based educational games became popular in the 1960s and 1970s, but waned under the Back to Basics teaching movement. The Back to Basics teaching movement is a change in teaching style that started in the 1970s when students were scoring poorly on standardized tests and exploring too many electives. This movement wanted to focus students on reading, writing and arithmetic and intensify the curriculum.

With the proliferation of computers in the 1980s, the use of educational games in the classroom became popular with titles that included “Oregon Trail,” “Math Blaster,” and “Number Munchers.” Though these games were popular among teachers and students, they were also criticized due to the fact that they did not provide the player with new kinds of learning, and instead provided a slightly easier-to-swallow version of drill-and-practice learning.

In the 1990s, newer games such as “The Incredible Time Machine” and “Dr. Brain” were introduced to challenge kids to think in new ways, apply their current skills, and learn new ones, but these games were unpopular among teachers because it was difficult to map these newer games to their curriculum, especially in a high school setting where in-class time is at a premium. The 1990s also saw the Internet being introduced to schools, which with limited computer resources took precedence over playing games.

In the 1990s, newer games such as “The Incredible Time Machine” and “Dr. Brain” were introduced to challenge kids to think in new ways, apply their current skills, and learn new ones, but these games were unpopular among teachers because it was difficult to map these newer games to their curriculum, especially in a high school setting where in-class time is at a premium. The 1990s also saw the Internet being introduced to schools, which with limited computer resources took precedence over playing games.

The early 2000’s saw a surge in different types of educational games, especially those designed for the younger learner. Many of these games were not computer-based but took on the model of other traditional gaming system both in the console and hand-held format. In 1999 LeapFrog Enterprises introduced the “LeapPad,” which combined an interactive book with a cartridge and allowed kids to play games and interact with a paper-based book. Based on the popularity of traditional hand-held gaming systems like Nintendo’s “Game Boy,” they also introduced their hand-held gaming system called the “Leapster” in 2003. This system was cartridge-based and integrated arcade–style games with educational content.

In 2002 another movement had started outside of formal educational sector that was coined as the “Serious Game Movement,” which originated from the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars where David Rejecsk and Ben Sawyer started the initiative. A “Serious Game” is considered a mental contest, played with a computer in accordance with specific rules that uses entertainment to further government or corporate training, education, health, public policy, and strategic communication objectives.

The primary consumer and producer of serious games is the United States Military, which needs to prepare their personnel for enter a variety of environments, cultures, and situations. They need to understand their surroundings, be able to communicate, use new technologies and quickly make decisions. The first serious game is often considered to be “Army Battlezone,” an abortive project headed by Atari in 1980, designed to use the “Battlezone” tank game for military training. Two other well-known serious games that were commissioned by the Army are “American Army” (2002) and “Full Spectrum Warrior” (2004).

The primary consumer and producer of serious games is the United States Military, which needs to prepare their personnel for enter a variety of environments, cultures, and situations. They need to understand their surroundings, be able to communicate, use new technologies and quickly make decisions. The first serious game is often considered to be “Army Battlezone,” an abortive project headed by Atari in 1980, designed to use the “Battlezone” tank game for military training. Two other well-known serious games that were commissioned by the Army are “American Army” (2002) and “Full Spectrum Warrior” (2004).

Outside of the government, there is substantial interest in serious games for formal education, professional training, healthcare, advertising, public policy and social change. For example, games from websites such as Newsgaming.com are “very political games groups made outside the corporate game system that are raising issues through media but using the distinct properties of games to engage people from a fresh perspective,” says Harry Jenkins, the director of MIT’s Comparative Media Studies Program. Such games, he said, constitute a “radical fictional work.” – Wikipedia

THE NATURE OF LEARNING GAMES

(The following is an abstract from “Games for the Digital Age: K-12 Market Map and Investment Analysis” a report by the Games and Publishing Council – winter 2013)

Digital games have been characterized as having four traits:

- A goal

- Rules

- A feedback system

- Voluntary participation

They are a voluntary activity structured by rules with a defined outcome (winning, losing) or other quantifiable feedback such as “points” that help comparisons of in-player performances. Learning games differ from training games because they… “target the acquisition of knowledge as its own end and foster habits of mind and understanding that are generally useful or useful within an academic context.”

• Learning games are not a single type. Rather, they are best understood in terms of the functions they serve in the school context.

• In terms of selling to the K-12 market, understanding the continuum from short-form to long-form games is critical.

• Short-form games provide tools for practice and focused concepts. They fit easily into the classroom time period and are especially attractive to schools as part of collections from which individual games can be selected as curricular needs arise.

• Long-form games have a stronger research base than short-form games and are focused on higher order thinking skills that align more naturally with new common core standards. These games do not fit as easily into the existing school day or classroom time period, but are the source of new experimentation in the research community and a variety of school contexts.

The language of gaming and learning games is still in flux, and there has been little agreement between experts in the field about what falls under the category of “learning game” and what is not a game, but has “game-like” elements. Not surprisingly, the literature of games contains no agreed upon definition of a learning game. Some say, “formative assessment based on an adaptive engine,” while the other cited products with aspects of game mechanics such as badges, rewards, and points.

The language of gaming and learning games is still in flux, and there has been little agreement between experts in the field about what falls under the category of “learning game” and what is not a game, but has “game-like” elements. Not surprisingly, the literature of games contains no agreed upon definition of a learning game. Some say, “formative assessment based on an adaptive engine,” while the other cited products with aspects of game mechanics such as badges, rewards, and points.

Such a wide range of products is confusing to the K-12 audience, because “games” can vary from products that are prototypical to ones that only leverage somewhat extraneous game mechanics to engage and to motivate. Confusion among types of games is of particular concern when examining the research evidence of the effectiveness of games in learning. Most university-based research evaluates learning games in environments that engage students for several weeks with immersive, challenging experiences. Thus, when researchers argue that learning games are efficacious, promote critical thinking, and engage 21st century skills, it is not necessarily clear that these conclusions apply to many shorter forms of learning games.

All games have game mechanics that are the central element of the game and, to some degree, are integrated with the learning content. The extent to which the mechanics of creating motivation and directing attention is intrinsic to the content of the game can greatly influence learning outcomes.

Gamification

Gamification is the use of game-based elements or game mechanics to drive user engagement and actions in non-game contexts. In gamification, the game mechanics are divorced from the content being taught and are instead added in the form of some sort of reward element after completion of an activity. For example, a short-form math game that involves answering math questions where correct answers are followed by a badge or the reward of playing a “dunk the clown” game would be called gamification. Some are concerned that this use of game mechanics can begin to undermine a kid’s desire to learn.

math questions where correct answers are followed by a badge or the reward of playing a “dunk the clown” game would be called gamification. Some are concerned that this use of game mechanics can begin to undermine a kid’s desire to learn.

There are many different types and “degrees” of learning games, so that any such categorization must encompass a loosely structured “family of meanings” where learning games can be grouped and seen to possess some, but not always all, of the same traits. Some of these more specific traits include objectives, outcomes, feedback, conflict, competition, challenge, opposition, interaction, and representation of story. Learning games can be purposeful, goal-oriented, rule-based activities that the players perceive as fun as they move beyond entertainment per se to deliver engaging interactive media to support learning in its broadest sense.

Short-Form Learning Games

In most K-12 schools the day is organized in blocks of time that average 40 minutes or less. Transition time and time for instruction or discussion connected to curricular material frequently leaves only 20 to 30 minutes for actually using a learning game. Short-form games are interactive digital activities that fit within a single class period and have some components common to all learning games. They focus on a particular concept or on skill refinement, skills practice, memorization, or performing specific drills.

Successful short-form games meet an important and defined market need, whether it is by demonstrating a concept to the whole class on an interactive white board, or by providing individual students with practice on a specific concept or skill. Short-form games include drill and practice, brief simulations, visualizations, or simulated training tools, and different types of “game-like” interactive learning objects. These types of games have the potential to be embedded in personalized learning environments or adaptive engines that combine data and feedback loops that are becoming increasingly popular in schools.

This type of game product is starting to gain traction in the K-12 market, due in part to its alignment to standards and to extensive product lines that cover many topics within the curriculum or meet an important, albeit narrow, market need. Teachers find such games easy to access and understand, and the games fit neatly into the short blocks of time available in the structured school day.

Long-Form Learning Games

Long-form learning games extend beyond a single class period. Typically game playing is spread over multiple sessions or even several weeks. Long-form games lend themselves to the development of 21st century skills such as critical thinking, problem solving, collaboration, creativity, and communication. There is a distinction between the sophisticated learning skills developed through immersive experiences versus games where students are rewarded for memorizing vocabulary words or performing math drills. Games such as Civilization III have the potential to push students to engage actively in problem solving, reflection, and decision making related to historical and political situations. Long-form, immersive game play as a critical factor supporting a broad arena of social and cognitive learning.

learning skills developed through immersive experiences versus games where students are rewarded for memorizing vocabulary words or performing math drills. Games such as Civilization III have the potential to push students to engage actively in problem solving, reflection, and decision making related to historical and political situations. Long-form, immersive game play as a critical factor supporting a broad arena of social and cognitive learning.

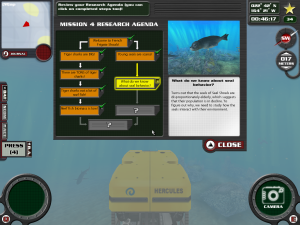

A number of individual studies have demonstrated that specific long-form games perform better when compared to typical lectures. Examples from research studies include Supercharged!, an electrostatics game that showed a 28% increase in learning; Geography Explorer, a geology game that showed a 15 to 40% increase in learning; Virtual Cell, a cell biology game that showed a 30–63% increase in learning; and River City, a game that showed a 370% increase in learning for D students and 14% increase for B students.

Recent research also points to the significance of the engagement factor produced by long-form learning games. Engagement fosters motivation and keeps students involved in the learning experience. While many educational software products have focused on extrinsic rewards for skills practice, longer form games where game play and learning are closely connected have been proven to be even more engaging than following a learning task with an external reward.

Recent research also points to the significance of the engagement factor produced by long-form learning games. Engagement fosters motivation and keeps students involved in the learning experience. While many educational software products have focused on extrinsic rewards for skills practice, longer form games where game play and learning are closely connected have been proven to be even more engaging than following a learning task with an external reward.

The authors of a report issued by the Committee on Science Learning at the National Research Council concluded that simulations and games have great potential to improve science learning in the classroom because they can individualize learning to match the pace, interests, and capabilities of each particular student and contextualize learning in engaging virtual environments. The authors also echoed previous research demonstrating the appeal and engagement of learning games, and indicate that games can help support new inquiry-based approaches to science instruction by providing virtual laboratories or field learning experiences that overcome practical constraints.

The time required for playing long-form games has proven to be a significant barrier to their widespread adoption. Long-form games can more easily fit into a homework element and that class time can be reserved for discussing results of the homework activities, strategies, and content learned. This “flipped classroom” model addresses the classroom time factor in that teachers can control how much time is spent on discussion sessions. However, there remain challenges with connectivity for students from lower income households. As more schools experiment with various forms of online and blended learning (see: Blended-based Learning), a better fit between available class time and long-form games may emerge.

COMPUTER GAME STRUCTURE

Computer games are developed by using game design software like Unity. Unity can fully develop entire custom games in a 3D browser based environment. Unity technology is a tool most commonly used for video game development, architectural visualizations and interactive media installations. As a multi-platform design tool, Unity game design allows games to be easily published to the web, Windows, Wii, Xbox 360 and iPhone, with many more platform options on the horizon.

Game Design Software (GDS) can:

- Develop “serious” games with a small 3MB plug in

- Help track the progress of students by tying the game into Learning Management Systems (LMS)

- Teach students using an interactive method to increase interest and understanding

- Allow multiplayer use

- Create games usable in a variety of platforms and for many uses

The term “serious games” sounds like a contradiction, but it’s not. The term actually refers to a game designed for educational or training purposes. The “serious” adjective can refer to products used by industries like defense, education, scientific exploration, health care, emergency management, city planning, engineering, religion, and politics. “Gamification” of learning is exploding as computer and Internet-savvy young people enter the workforce and their employers strive to teach and train them in efficient ways for the 21st century.

refer to products used by industries like defense, education, scientific exploration, health care, emergency management, city planning, engineering, religion, and politics. “Gamification” of learning is exploding as computer and Internet-savvy young people enter the workforce and their employers strive to teach and train them in efficient ways for the 21st century.

According to a study by the Entertainment Software Association, 70 percent of major employers utilize interactive software and games to train employees. Additionally, more than 75 percent of businesses and non-profits already offering video game-based training plan to expand their usage in the next 3 to 5 years.

i.pel will be developing high quality interactive serious games that are educational and aesthetically appealing. All i.pel curriculum courses that use game supplements will have imbedded educational game features which are designed to aid teaching and enhance the learning experience of students.

Based on their initial set of interviews, Games for a Digital Age, created a matrix of more than 30 game characteristics or key variables to classify and characterize learning games. This model was tested by placing current games into our matrix (see Appendix A) of the report. The matrix is oriented toward the K-12 institutional market that will assist developers and others in determining what types of games will have a higher chance of success.

Game Taxonomy

(Abstract from Games for a Digital Age)

In a comprehensive review of the research literature on learning games it was concluded that the findings on learning from games and the transfer of that learning to external tasks are “less robust than one might wish.” A development of a taxonomy of games should be developed in order to help clarify future research on what types of outcomes might be expected from what types of games and for what types of students. It also is critical to develop such a taxonomy in light of the distinction between short-form to long-form games.

Taxonomies have attempted to classify learning games for a variety of goals. They typically focus on efficacy research and on determining whether a particular game type is effective for particular types of learning. Games have been divided into the following types:

- Action

- Adventure

- Puzzle

- Role-Playing

- Simulations

The game map developed for this report builds on previous attempts at game taxonomies, (including more recent taxonomies developed by Squire, 2008; Wilson, et al. 2009; Liu & Lin, 2009; Frazer, Argles, & Willis, 2008; and others). However, it is primarily related to marketing into the institutional market for learning games, and only secondarily on issues of learning games and efficacy. This taxonomy synthesizes previous attempts to develop a list of types of learning games.

2009; Frazer, Argles, & Willis, 2008; and others). However, it is primarily related to marketing into the institutional market for learning games, and only secondarily on issues of learning games and efficacy. This taxonomy synthesizes previous attempts to develop a list of types of learning games.

Computer Game Genres

The following categories or genres were created with the assumption that some degree of overlap between categories is inevitable:

1. Drill and Practice

2. Puzzle

3. Interactive Learning Tools

4. Role Playing

5. Strategy

6. Sandbox

7. Action/Adventure

8. Simulations

1.Drill and Practice

Drill and practice activities are the prototypical short-form games. They are focused on the acquisition of factual knowledge or skill development through repetitive practice. Small tasks such as the memorization of vocabulary word definitions, math facts, or touch typing skills are the focus of drill and practice games. Many online interactive drill and practice programs provide some sort of game mechanic to bolster student engagement.

Sometimes the game mechanic is integrated into the learning content and sometimes it comes at the end of a group of activities in the form of gamification such as providing the student with a small  reward or the opportunity to play a quick game after achieving a certain score on the content learning portion of the tool. Some drill and practice games also provide an instructional component in addition to the quiz or practice piece, are able to provide feedback on right and wrong answers, differentiate instruction according to student responses, provide data for teachers and administrators, and can be used in conjunction with teacher-led classroom activities. One of the most successful drill and practice programs from the late 1980’s, MathBlaster, is still available from Knowledge Adventure.

reward or the opportunity to play a quick game after achieving a certain score on the content learning portion of the tool. Some drill and practice games also provide an instructional component in addition to the quiz or practice piece, are able to provide feedback on right and wrong answers, differentiate instruction according to student responses, provide data for teachers and administrators, and can be used in conjunction with teacher-led classroom activities. One of the most successful drill and practice programs from the late 1980’s, MathBlaster, is still available from Knowledge Adventure.

Motion Math produces learning games that are played on mobile devices or tablets. Motion Math HD, the first Motion Math product, is a fractions number line game developed at the Stanford School of Education and launched successfully in 2010 with investment and foundation support. The learning piece—e.g. understanding fractions, percentages, decimals, and pie charts—is directly connected to the game mechanic so that, for example, learners steer a bouncing ball to the correct spot on a number line. Motion Math is standards-based and grounded in research that, among other things, suggests that learning is enhanced when physical experiences connect to intellectual content, and that learning games work best when there is no separation between game play and content learning.

Motion Math produces learning games that are played on mobile devices or tablets. Motion Math HD, the first Motion Math product, is a fractions number line game developed at the Stanford School of Education and launched successfully in 2010 with investment and foundation support. The learning piece—e.g. understanding fractions, percentages, decimals, and pie charts—is directly connected to the game mechanic so that, for example, learners steer a bouncing ball to the correct spot on a number line. Motion Math is standards-based and grounded in research that, among other things, suggests that learning is enhanced when physical experiences connect to intellectual content, and that learning games work best when there is no separation between game play and content learning.

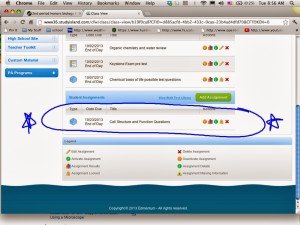

Study Island produces a variety of web-based drill and practice programs. These include assessment and skills practice in all major subject areas and are aligned to state and Common Core standards.7 Students take a pre-test and are then provided with drills that target their needs and level. Then, after successfully completing lesson units, students are rewarded with a choice of short motivational games. The program further provides teachers with assessment data.

2. Puzzle Games

Puzzle games emphasize problem-solving skills often involving shapes, colors, or symbols that the player must directly or indirectly manipulate into a specific pattern. Tetris is an example of a classic puzzle game.

Tetris is short-form in design. A new variety of long-form puzzle games present a series of related puzzles that contain a variation on a single theme such as pattern recognition, logic, or the understanding of a specific process. Typically players must unravel clues to achieve a win state, which then allows them to level up.

Foldit is a puzzle learning game focused on protein folding. Designed by a research team at the University of Washington’s Center for Game Science, this game’s objective revolves around folding the structure of selected proteins using various tools provided within the game. Researchers analyze the highest scoring solutions to determine whether there is a native, structural configuration that can be applied to the relevant proteins in the “real world.” Scientists can then use such  solutions to solve real-world problems by targeting and eradicating diseases and creating biological innovations. This game makes use of crowdsourcing and distributed computing as well as gamification to make the program more appealing to a wider audience. Learners using the game are given a score and can join groups and share solutions. Remarkably, a team of gamers used Foldit to solve the structure of a retrovirus from an AIDS-like virus that had previously stumped scientists (University of Washington, 2011).

solutions to solve real-world problems by targeting and eradicating diseases and creating biological innovations. This game makes use of crowdsourcing and distributed computing as well as gamification to make the program more appealing to a wider audience. Learners using the game are given a score and can join groups and share solutions. Remarkably, a team of gamers used Foldit to solve the structure of a retrovirus from an AIDS-like virus that had previously stumped scientists (University of Washington, 2011).

3. Interactive Learning Tools

Interactive learning tools or objects are short pieces of online instruction that can be easily integrated into a larger curriculum. These items can have game-like properties or can be connected to games or rewards. In the K-12 world, learning objects can be short animations, videos, interactive quizzes, or other tools.

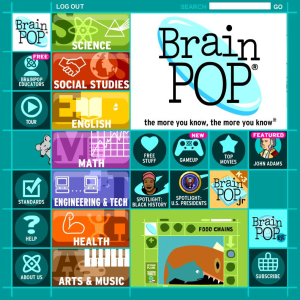

BrainPOP, frequently thought of as a game, is essentially more than 1,000 animated lessons with interactive items like quizzes attached. Its short animations and interactive tools cover science, social studies, English, math, arts, music, health, and technology and have been aligned with curriculum standards by state. The site was marketed initially to parents and became very popular in the consumer market, transitioning gradually into schools. Similar to the drill and practice games mentioned above, these short-form animations fit easily into the school day. Teachers understand what they are, how to make use of them for limited parts of the school day, and how to use them to meet specific learning goals such as memorizing math facts or learning about George Washington.

BrainPOP has also added a new product for younger children called BrainPOP Jr., which incorporates games into each brief animation. The site now links their interactives to various free learning games available through a portal called Game-Up.

4. Role Playing

Role-playing games portray some sequence of events within the game world which gives the game a narrative element. Players have a range of options for interacting with the game  world through their characters and can take multiple paths or double back and revisit times of places they have previously explored (Hitchens & Drachen, 2009). Roleplaying games are particularly useful for subjects such as social studies, for example, where students can be immersed in a specific time period in history and grapple with challenges that occurred at the time being studied in order to more fully comprehend concepts such as slavery or civics.

world through their characters and can take multiple paths or double back and revisit times of places they have previously explored (Hitchens & Drachen, 2009). Roleplaying games are particularly useful for subjects such as social studies, for example, where students can be immersed in a specific time period in history and grapple with challenges that occurred at the time being studied in order to more fully comprehend concepts such as slavery or civics.

Multi-User Virtual Environments (MUVEs) are a form of role-playing and simulation games that enable participants to access virtual worlds, interact with online artifacts, represent themselves online via an avatar, communicate with other participants, and take part in experiences that model real world environments (Dede, Nelson, Ketelhut, Clarke & Bowman, 2004).

Early role-playing games such as Oregon Trail were immensely successful in schools. In this simulation, students played roles that required successful navigation of the onerous conditions that pioneers encountered in the Westward expansion.

iCivics is a web-based learning game founded by former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. It is designed to teach civics and inspire students to be active participants in U.S. democracy. iCivics includes role-playing games that simulate such things as being “President for a Day” or arguing a case before the Supreme Court. This game is aligned to state standards and includes teacher materials, lesson plans, and PowerPoint presentations. Its modularized format is especially appealing to teachers, allowing them to select specific pieces of the content and connect that content to state standards. iCivics is a free resource to schools.

democracy. iCivics includes role-playing games that simulate such things as being “President for a Day” or arguing a case before the Supreme Court. This game is aligned to state standards and includes teacher materials, lesson plans, and PowerPoint presentations. Its modularized format is especially appealing to teachers, allowing them to select specific pieces of the content and connect that content to state standards. iCivics is a free resource to schools.

Similarly, Mission U.S. is a series of multiplayer games that immerse players in U.S. historical content. “For Crown r Colony?” places the player in the role of a printer’s apprentice in 1770 Boston. In “Flight to Freedom” the player is a slave in Kentucky in 1848. It is funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting with several partners in the non-profit sector.

River City is a research-based project funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) that involves an interactive computer simulation for middle grade science students to learn scientific inquiry and 21st century skills. It combines the look and feel of a learning game with content developed from National Science Education Standards and the National Educational Technology Standards.

The creators of River City were well aware of the challenging nature of introducing immersive games into the formal education environment, the challenges specific to middle school students, and issues of engagement and teacher reluctance to learn new technologies. As the product was created, the developers addressed these issues to the degree possible and tried to solve the challenges of scalability. In the end, after years of successful research and development, River City did not have the kind of funding needed to go to market on its own and could not find an industry partner willing to take the product to market, even when it was offered for free.

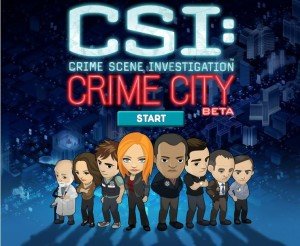

CSI, also funded by the NSF as well as Rice University, CBS, and the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, is a series of role-playing games based on the CSI television series designed to teach students the process of forensic investigation and problem solving. CSI is known for its extremely high quality graphics and navigational features that rival games in the consumer market.

Martha Madison, a new game currently being designed by Second Avenue Software, also uses role-playing to teach students. It is focused on engaging girls in STEM learning and careers. The game is being created using the Unity 3D platform, which allows for publishing to a diverse array of applications including tablets, computers, consoles, and mobile devices. Martha Madison is being designed to align with emerging Common Core standards in science.

Martha Madison, a new game currently being designed by Second Avenue Software, also uses role-playing to teach students. It is focused on engaging girls in STEM learning and careers. The game is being created using the Unity 3D platform, which allows for publishing to a diverse array of applications including tablets, computers, consoles, and mobile devices. Martha Madison is being designed to align with emerging Common Core standards in science.

5. Strategy

Strategy games are multiplayer games involving resource management, planning, and strategic deployment (Frazer et al., 2008). The most successful strategy games are in social studies and history.

Civilization V is an incredibly popular consumer strategy game (over nine million units sold worldwide) developed by Firaxis. Players strive to become “Ruler of the World” by establishing and leading a civilization from prehistoric times into the space age, and make strategic decisions regarding diplomacy, expansion, economic development, technology, government, and military conquest.

Civilization has made inroads into the K-12 market albeit with some reservations. At issue: Historical accuracy and whether students are in fact learning the properties of complex systems or just simple heuristics that help them succeed in the game (Squire & Durga, in press). The game exposes players to historical content and asks them to balance multiple variables, as well as make tradeoffs related to financial, military, technological, and cultural issues. Under the best of circumstances, students use the game “…as a model to think about history and the design of social systems”

Making History II: The War of the World is a multiplayer strategy game developed by Muzzy Lane Software that takes place in the years up to and including World War II. Players take control of nation-level trade and diplomacy, industrial and technology development, transportation infrastructure, and military movement and deployment. The product originally targeted schools, but caught on in the consumer space. Muzzy Lane sold 50,000 copies of this game at $39.99 a piece, with about 10-20% of these sales going to the K-12 classroom. (K-12 discounts for packs of 5 and 10 and units of 25 for $500 were also sold.) A sequel, Making History: The Great War takes place in the years up to and including World War I.

Making History II: The War of the World is a multiplayer strategy game developed by Muzzy Lane Software that takes place in the years up to and including World War II. Players take control of nation-level trade and diplomacy, industrial and technology development, transportation infrastructure, and military movement and deployment. The product originally targeted schools, but caught on in the consumer space. Muzzy Lane sold 50,000 copies of this game at $39.99 a piece, with about 10-20% of these sales going to the K-12 classroom. (K-12 discounts for packs of 5 and 10 and units of 25 for $500 were also sold.) A sequel, Making History: The Great War takes place in the years up to and including World War I.

Sandboxes are open-ended exploration environments rather than linear, goal-oriented games. They are characterized by multiple user paths and open-ended structures. These games tend to be highly learner centered, designed to foster 21st century skills including problem-solving, collaboration, and creativity, and frequently allow players to experiment with the mechanics of game play. Some Sandbox games also allow different content to be placed within the Sandbox “container, versatility that can often appeal to teachers. Sandbox games follow in a tradition of student construction that derives from the Logo programming movement in the 80’s and 90’s, which despite never becoming commercially successful, has certainly captured the imagination of researchers and  educators (Feurzeig, Papert, Bloom, Grant & Solomon,1969; Papert, 1980).

educators (Feurzeig, Papert, Bloom, Grant & Solomon,1969; Papert, 1980).

Scratch is a programming language that makes it easy to create interactive stories, animations, games, music, and art that follows in the Logo tradition and was developed by the Lifelong Kindergarten Group at the MIT Media Lab. A critical component is the Scratch Online Community where students are able to share and augment projects, download others’ work, open it up to see how it was created, make changes and upload a new version.

Minecraft is a consumer game where players place blocks to build anything they can imagine in order to survive monsters that come out at night. This popular product has sales of more than 7 million units and an educational adaptation, MinecraftEdu. The adaptation further offers custom versions designed for teachers and students, onsite workshops and in-service training, and world-building tools that make it easier to incorporate curricular content. A video case study of its use in the classroom is available at on the Joan Ganz Cooney Center website.

7. Action/Adventure

Action/Adventure games typically involve players traveling to an unknown space or environment, often in the role of a traveler or warrior. Some action/adventure games include  fighting games, and most action/adventure games are massive multiplayer online games. Lure of the Labyrinth is designed for middle-school pre-algebra students. It includes a large number of math-based puzzles wrapped into a narrative game in which students work to find their lost pet and save the world from monsters. The developers have created extensive resources to help teachers incorporate the game in their teaching. Originally developed in 2007 at the MIT Education Arcade, Lure of the Labyrinth is designed to be used by students outside of the classroom. Teachers and students then use class time to discuss the strategies students used and concepts discovered in playing.

fighting games, and most action/adventure games are massive multiplayer online games. Lure of the Labyrinth is designed for middle-school pre-algebra students. It includes a large number of math-based puzzles wrapped into a narrative game in which students work to find their lost pet and save the world from monsters. The developers have created extensive resources to help teachers incorporate the game in their teaching. Originally developed in 2007 at the MIT Education Arcade, Lure of the Labyrinth is designed to be used by students outside of the classroom. Teachers and students then use class time to discuss the strategies students used and concepts discovered in playing.

This game is designed to foster collaborative skills and includes a messaging system as a function of game play, giving the students the opportunity to share strategies and work in teams. Lure of the Labyrinth also provides teachers with assessment data on student work.

8. Simulations

A learning simulation is the manipulation of a model of some event in such a way that it operates on time, space, or magnitude to exert change. Kurt Squire argues that “if it is not a simulation on some level, it is probably not a good educational game” (CS4Ed interview, June 2012). Many simulations clearly lack the dynamics typical of games, but some overlap a great deal with games types such as strategy and sandbox. In an early analysis of simulations as learning tools (and the Sim series by Maxis in particular), Star expresses concern about  the assumptions and simplifications built into any simulation (Star, 1994).

the assumptions and simplifications built into any simulation (Star, 1994).

Often, simulations do not have the true mechanics that would characterize them as games, but for the purposes of this report both longer simulations and brief simulations are being included in the broad category of learning games. Short, two or three minute simulations or visualizations have been developed for many content areas, but are probably most common in the K-12 sciences or more broadly in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) fields. Simulations are common in adult training environments as well. Short simulations can require a significant amount of resources to develop, but can fit easily into a classroom curriculum. Molecular Workbench is a collection of free, interactive, scientific simulations and learning modules developed by the Concord Consortium with support from the National Science Foundation (NSF). The simulations are typically used within a larger curriculum where they can help demonstrate concepts discussed in class such as gas laws, diffusion heat transfer, chemical reactions, and fluid mechanics, and student progress can be tracked (Project WISE at University of California, Berkeley; Linn 2012). Molecular Workbench also acts as a tool for students to create their own simulations in order to  demonstrate their own learning of scientific concepts.

demonstrate their own learning of scientific concepts.

MiddWorld Online is a web-based quest and role-play simulation. Students immerse themselves in culturally accurate environments (such as going to a café in Paris and ordering coffee), while practicing their language skills and using target language vocabulary while interacting with non-player characters and other students in the environment. The MiddWorld game framework is also designed so that the games can be replicated for other languages and cultures in addition to their initial versions for Spanish and French.

Whitebox Learning designs simulations using CAD to provide a simplified version of a realistic development process such as building a bridge or dragster while simulating the scientific method. Students can then analyze, test, and evaluate what they’ve built through virtual game play that involves, for example, a drag race or monster truck rally. Like many learning simulations, the Whitebox Learning System was created as a complement to hands-on activities; students explore designs in the simulated environment and then go on to build real world models based on these explorations.

EcoMUVE is a curriculum research project at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education that uses immersive simulations to teach middle school students about  causal patterns within ecosystems. The project includes two one-week computer based modules that take place in a four-week curriculum, and uses a Multi-User Virtual Environment (MUVE) that has the look and feel of a commercial videogame. Also similar to a commercial gaming environment, here students explore and collaborate in teams, but their purpose is to learn science by exploring and solving problems within a realistic simulation. The curriculum uses a jigsaw pedagogy in which each student plays a different role (e.g., water quality specialist, naturalist, microscopic specialist, investigator) and data is generated from student activities that provide embedded assessment.

causal patterns within ecosystems. The project includes two one-week computer based modules that take place in a four-week curriculum, and uses a Multi-User Virtual Environment (MUVE) that has the look and feel of a commercial videogame. Also similar to a commercial gaming environment, here students explore and collaborate in teams, but their purpose is to learn science by exploring and solving problems within a realistic simulation. The curriculum uses a jigsaw pedagogy in which each student plays a different role (e.g., water quality specialist, naturalist, microscopic specialist, investigator) and data is generated from student activities that provide embedded assessment.

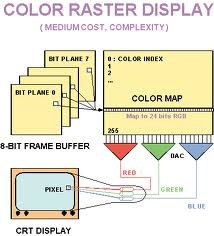

A video game is an electronic game that involves human interaction with a user interface to generate visual feedback on a video device. The word video in video game traditionally referred to a raster display device, but following popularization of the term “video game”, it now implies any type of display device.

The electronic systems used to play video games are known as platforms. Examples of these are personal computers and video game consoles. These platforms range from large mainframe computers to small handheld devices. Specialized video games such as arcade games, while previously common, have gradually declined in use. Video games have gone on to become a legacy art form.

The input device used to manipulate video games is called a game controller, and varies across platforms. For example, a controller might consist of only a button and a joystick, while another may feature a dozen buttons and one or more joysticks. Early personal computer games often needed a keyboard for gameplay, or more commonly, required the user to buy a separate joystick with at least one button. Many modern computer games allow or require the player to use a keyboard and a mouse simultaneously. A few of the most common game controllers are gamepads, mice, keyboards, and joysticks. Video games can also be used in an educational atmosphere.

The input device used to manipulate video games is called a game controller, and varies across platforms. For example, a controller might consist of only a button and a joystick, while another may feature a dozen buttons and one or more joysticks. Early personal computer games often needed a keyboard for gameplay, or more commonly, required the user to buy a separate joystick with at least one button. Many modern computer games allow or require the player to use a keyboard and a mouse simultaneously. A few of the most common game controllers are gamepads, mice, keyboards, and joysticks. Video games can also be used in an educational atmosphere.

Video games and education have a complex and layered relationship. There are many video games with educational value. “Edutainment” describes an intentional merger of computer games and educational software into a single product. The term describes educational software which is primarily about entertainment, but tends to educate as well. Software of this kind is not structured towards school curricula, does not normally involve educational advisors, and does not focus on core skills such as literacy and numeracy.

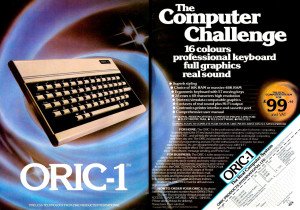

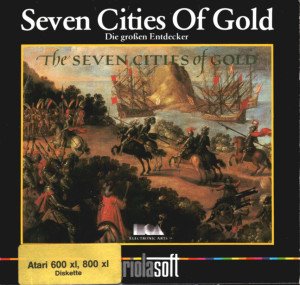

In the UK In 1983 the term Edutainment was used to describe a package of software games for the Oric 1 and Spectrum Microcomputers. Dubbed “arcade edutainment” an advertisement for the package can be found in various issues of “Your Computer” magazine from 1983. The software package was available from Telford ITEC a government sponsored training program. The originator of the name was Chris Harvey who worked at ITEC at the time. Since then, many other computer games such as Electronic Arts computer game “Seven Cities of Gold,” released 1984, have also used the term edutainment to describe their product. Most edutainment

In the UK In 1983 the term Edutainment was used to describe a package of software games for the Oric 1 and Spectrum Microcomputers. Dubbed “arcade edutainment” an advertisement for the package can be found in various issues of “Your Computer” magazine from 1983. The software package was available from Telford ITEC a government sponsored training program. The originator of the name was Chris Harvey who worked at ITEC at the time. Since then, many other computer games such as Electronic Arts computer game “Seven Cities of Gold,” released 1984, have also used the term edutainment to describe their product. Most edutainment games seek to teach players using a game based learning approach. Criticism as to what video games can be considered “educational” has led to the creation of the above mentioned “serious games” whose primary focus is to teach rather than entertain.

games seek to teach players using a game based learning approach. Criticism as to what video games can be considered “educational” has led to the creation of the above mentioned “serious games” whose primary focus is to teach rather than entertain.

Simon Egenfeldt-Nielsen (PhD, Psychologist) has spent a great deal of time researching the educational use and potential of computer games and has written many articles on the subject. One paper dealing specifically with Edutainment breaks it down into 3 generational categories to separate the cognitive methods most predominantly used to teach. In his papers he is critical of the research that has been done in the areas of the educational use of computer games cited their biases and weaknesses in method causing them to lack scientific validity in their findings.

Educating With Video Games

Since their arrival to platforms in the 1970s, video games have risen to be one of the biggest consumer markets on the globe. Today it is very rare to enter someone’s home without finding at least a computer with some version of a game installed onto it. Video games have been in the midst of controversy since their release for having things such as excessive violence or for having seemingly no value to the daily lives of an individual, and granted that there are almost certainly some games like that, but with so many people purchasing them year in and year out one might reason that an education could be gained, even in the smallest sense, from these electronic wonders.

to enter someone’s home without finding at least a computer with some version of a game installed onto it. Video games have been in the midst of controversy since their release for having things such as excessive violence or for having seemingly no value to the daily lives of an individual, and granted that there are almost certainly some games like that, but with so many people purchasing them year in and year out one might reason that an education could be gained, even in the smallest sense, from these electronic wonders.

The greatest games are the ones that are bought and learned. Gamers will take the time to develop knowledge about all aspects of the game, and thus the game will be played for a long time with great attention to it. This is the main goal of the developers; to create a game that will capture the attention of the player in such a way that he or she will want to keep playing. Video games can also be used as an alternative to a classroom setting, while still maintaining levels of difficulty that foster learning in a gamer.

In today’s modern times the census indicates that in 2012, 190 million American households will own a next generation video game console. With the amount of home consoles on the rise, it is easy to distinguish that video games and video game culture is becoming a social norm for the U.S. and the world as well. With the average age of a gamer dropping every year, more and more young people are becoming comfortable in the gaming community.

In today’s modern times the census indicates that in 2012, 190 million American households will own a next generation video game console. With the amount of home consoles on the rise, it is easy to distinguish that video games and video game culture is becoming a social norm for the U.S. and the world as well. With the average age of a gamer dropping every year, more and more young people are becoming comfortable in the gaming community.

Today, avid gamers will wait anxiously in line outside stores for the next big game like their parents did for concert tickets or willingly pay online fees every month much like their parents pay for their electric bill. The culture is wrapping itself around the young people in the world, and video games could be a great way to bring a new form of learning into the classroom. When someone plays a video game, they are challenged mentally with a problem. Through playing they will discover many different ways to solve problems they will come across.

In good games, they will often find that they will require these skills later on in the game as well, and thus be required to maintain and hone their skills for later on. Video games also often provide instant rewards for succeeding in solving a problem. This is in contrast to the classroom where students wait for graded tests and are only rewarded occasionally with report cards to report their progress. Video games can instantly tell a student of failure or success and often this can be used to develop skills along the way.

Compared to a Classroom Model

In a contemporary classroom model it is typical for the teacher to stand in front of the class and lecture to the students. Since some students will learn at different levels, it is possible that some students will be held back or some students will be left behind because of the pace of the class. In many good video games there are difficulty settings. This allows the player to set a different level of mastery for their individual needs. After the player has achieved mastery over the game, they can up the difficulty setting and be further challenged. Also while the teacher is engaging the class he or she is not specifically engaging any particular student.

It can be easy for students to get lost in their thoughts and disconnect from what is going on in class. Video games tend to be more engaging. Rather than getting a bunch of information over an extended class period, games provide small bits of information at relevant stages. It is true that many things students learn in their classroom will be relevant, but not necessarily at that particular moment. Video games will hold the attention of the player and provide what information is needed for that junction within the game.

Many games also involve varying levels of problem solving, requiring an active mind to help achieve completion of a goal. Not all games do this well, but the good games will provide game play that is do-able, but challenging enough that the student must work at its completion. Because games follow this model, it creates a small degree of frustration in the player but does not deter them from wanting to play. Instead it gives them more motivation to continue on. To get the full benefit from this many games allow players to adjust difficulty levels and allow them to achieve varying levels of mastery over the game.

Games like the God of War series show a good example of how this works. In the beginning of the game you will start off with all of your powers and upgrades, and this will help you develop basic skills. After a short period of time all of these helpful characteristics of your avatar are taken away. From here the gamer will play through the game and periodically be rewarded with new equipment or powers, either from experience of playing well or from reaching a certain point in the game.

Games like the God of War series show a good example of how this works. In the beginning of the game you will start off with all of your powers and upgrades, and this will help you develop basic skills. After a short period of time all of these helpful characteristics of your avatar are taken away. From here the gamer will play through the game and periodically be rewarded with new equipment or powers, either from experience of playing well or from reaching a certain point in the game.

These new items can be used to achieve success later in the game. If the gamer wanted to master the game, he or she would need to learn to utilize all of the upgrades that they are given. By giving the gamer upgrades periodically after a string of successes, the game holds theattention of the gamer to keep playing. Also by throwing equipment at the gamer at certain intervals, they can learn to use each piece individually and then later be stronger in using it.

Educational Setting

It is important to emphasize how video games interact with the learning process of adolescents and children. As early as 1978 research was started relating video games to the  motivational effects involved in learning as well as their cognitive potential. In the 1980s, with spread of video games, research grew and became more diversified. Most findings were consistent with their claims, stating that the visual and motor coordination of game players was better than that of non-players.

motivational effects involved in learning as well as their cognitive potential. In the 1980s, with spread of video games, research grew and became more diversified. Most findings were consistent with their claims, stating that the visual and motor coordination of game players was better than that of non-players.

Initial research also indicated the importance of electronic games for children who proved to have difficulty learning basic subjects and skills. Researchers have proved that video games helped students to identify their deficiencies and attempt to correct them. The adaptability of video games and the control that players have over them, motivate and stimulate learning, and in cases where students have difficulty concentrating can be highly useful. The instant feedback given by video games help arouse curiosity and in turn allow for greater chances of learning.

Video games can be highly useful in education in the sense that they create a simulation effect while not having any apparent danger involved. For instance, when the Air Force trains their pilots to fly a multi-million dollar plane, obviously they are not going to just send them up straight away. The Air Force uses piloting simulations in order to prepare their pilots for the real thing. These simulations are meant to prepare the training pilot for the real world while at the same time preventing any damage or loss of life in the process.

Video games can be highly useful in education in the sense that they create a simulation effect while not having any apparent danger involved. For instance, when the Air Force trains their pilots to fly a multi-million dollar plane, obviously they are not going to just send them up straight away. The Air Force uses piloting simulations in order to prepare their pilots for the real thing. These simulations are meant to prepare the training pilot for the real world while at the same time preventing any damage or loss of life in the process.

A pilot could crash in the simulation, learn from their mistake and then reset and try again. This process leads to distinct levels of mastery over the simulation and in turn the plane they will also be flying in the future. The Military also utilizes games such as the Call of Duty and SoCom franchises in their training. Games like these immerse the gamer into the realm of the game. Using tactical skills the players will attempt in the game to achieve whatever objective is set out for them. This allows for the military to show their soldiers how to engage certain situations with none of the risk of getting hurt in the line of battle.

Games of all types have been shown to increase a different array of skills for players. Attempts have been made to show that arcade style action and platforming games can be used to develop motor co-ordination, manual skills, and reflexes. Games have also been researched to find a connection with some kinds of games and stress relief. Many researchers have given claim to the educational potentials of games like The Sims for its social simulation or games like the Civilization series for its historical and strategy elements. Many conclude as a whole that video games promote intellectual development, and suggest that players can develop knowledge strategies, practice problem solving, and can greater develop spatial skills.

develop motor co-ordination, manual skills, and reflexes. Games have also been researched to find a connection with some kinds of games and stress relief. Many researchers have given claim to the educational potentials of games like The Sims for its social simulation or games like the Civilization series for its historical and strategy elements. Many conclude as a whole that video games promote intellectual development, and suggest that players can develop knowledge strategies, practice problem solving, and can greater develop spatial skills.

Using Video Games in the Classroom

Possible Benefits

Though they can be used outside a classroom setting, teachers have the capability to use video games within the classroom. There is substantial evidence which shows that for young children, educational video games promote student engagement and enhance the learning process while making it fun.

Video games are inherently incentive-based systems with the player being rewarded for solving a problem or completing the mission given certain criteria. Every single game has some form of rewards system, whether it’s based on points, achievements, character/weapon advancement, unlocking new material, or simply moving to the next level. Games can constantly and automatically assess the learner’s ability at every given moment, due to the software-based nature of the game; this is something that modular education structures lack in since they tend to be delivered in large chunks and present a relatively limited picture of student progress. Video games teach a systematic way of thinking as well as an understanding for how different variables affect each other. Video games also enhance reaction-based skills by providing the element of the unknown, which makes the player react naturally.

Games such as Minecraft and Portal provide perfect platforms for teachers to experiment with their educational abilities. While Minecraft is more of a free-for-all game in which the user can create virtually anything, Portal follows a more physics-based game style. The player uses the laws of physics, such as gravity and inertia, to advance through the game’s series of test chambers. Critical thinking and problem solving are inherent in the game’s design. Both Minecraft and Portal are very easily adaptable to different learning environments. Minecraft tends to be used more with children while Portal can be utilized by Physics teachers in high school.

Games such as Minecraft and Portal provide perfect platforms for teachers to experiment with their educational abilities. While Minecraft is more of a free-for-all game in which the user can create virtually anything, Portal follows a more physics-based game style. The player uses the laws of physics, such as gravity and inertia, to advance through the game’s series of test chambers. Critical thinking and problem solving are inherent in the game’s design. Both Minecraft and Portal are very easily adaptable to different learning environments. Minecraft tends to be used more with children while Portal can be utilized by Physics teachers in high school.

For example, one study showed that using a video game as part of class discussions, as well as including timely and engaging exercises relating the game to class material, can improve student performance and engagement. Instructors assigned groups of students to play the video game SPORE in a freshman undergraduate biology course on evolution. The group of students that was assigned to play SPORE and complete related exercises, in a total of 5 sessions throughout the semester, had average class scores about 4% higher than the non-gaming group. The game’s inaccuracies helped to stimulate critical thinking in students; one student said it helped her understand “the fine parts of natural selection, artificial selection, survival of the fittest, and genetic diversity because of the errors within the game. It was like a puzzle.” However, because the game was accompanied by additional exercises and instructor attention, this study is not overwhelming evidence for the hypothesis that video games in isolation increase student engagement.

Another source studied teachers using Civilization III in high school history classrooms, both during and after school. In this study, not all students were in favor of using the game. Many students found it too difficult and tedious. Some students, particularly high-performing students, were concerned about how it could affect their studies; they felt that “Civilization III was insufficient preparation for the ‘game’ of higher education.” However, students who were failing in the traditional school setting often did significantly better in the game-based unit. The game seemed to get their attention, where traditional schooling did not.

Teacher Resistance to Using Games

Despite the possible benefits, many teachers have reservations about using video games. One study asked teachers who had some experience using games in class why they didn’t do it  more often. Six general categories of factors were identified as problem areas:

more often. Six general categories of factors were identified as problem areas:

Inflexibility of curriculum: Teachers find it difficult to integrate games with the already-set curriculum present in classrooms. It can be difficult to locate a game that is educational as well as fun. And many teachers have no knowledge about how to teach with games.

Negative effects of gaming: Gaming can promote student addiction as well as physical problems. Students may also lose their desire to learn in the traditional setting. It can also remove teacher control and result in “excessive competition.”

Students’ lack of readiness: Students have varying levels of skill and computer literacy, which may be affected by their socioeconomic status. It takes time to teach them the rules of games, and games are harder for them to understand than traditional audiovisuals.

Lack of supporting materials: Teachers don’t have access to supporting text or work for students to do alongside games, and they have no external authorities to tell them which games are educational and which aren’t.

Lack of supporting materials: Teachers don’t have access to supporting text or work for students to do alongside games, and they have no external authorities to tell them which games are educational and which aren’t.

Fixed class schedules: Teachers have time constraints and their school may not allow them to use games.

Limited budgets: Computer equipment, software, and fast Internet connections are expensive and difficult for teachers to obtain.

All of the above were beliefs that teachers had about teaching with games that stopped them from doing so more. Some teachers were more concerned about some problems than others. Male teachers were less concerned about limited budgets, fixed class hours, and the lack of supporting materials than were female teachers. Inexperienced teachers were more worried about fixed class schedules and the lack of supporting materials than were experienced teachers.

Learning from Video Games outside the Classroom

There is much we can learn from video games outside the classroom as well. The “net generation” is intrinsically motivated by games and commercial video games have a potentially  important role to assist learning a range of crucial transferable skills. These games, referred to as “commercial off the shelf” (COTS) games are in a position to teach a mass audience of gamers certain techniques and skills.

important role to assist learning a range of crucial transferable skills. These games, referred to as “commercial off the shelf” (COTS) games are in a position to teach a mass audience of gamers certain techniques and skills.

One example of this would be in first-person shooter games such as the Call of Duty franchise. While by nature these games are violent and have been subject to massive negative reception by parents, it is still possible to learn key skills from the game. Games such as these stimulate the player at the cognitivelevel as they move through the level, mission, or game as a whole.

They also teach strategy, as players need to come up with ways to penetrate enemy lines, stealthily avoid the enemy, minimize casualties, etc. The multi-player aspect of these games proves to be the ultimate example of how well players utilize these skills. These games also allow  players to enhance their peripheral vision because they need to watch for movement on the screen and make quick decisions whether to shoot or not, depending on if it’s an enemy player or not.

players to enhance their peripheral vision because they need to watch for movement on the screen and make quick decisions whether to shoot or not, depending on if it’s an enemy player or not.

Other games such as the Guitar Hero and Rock Band franchises provide insight to the basic nature of education in video games. In order to succeed, you must fail multiple times and this is the only way to learn. These games also provide real-time feedback on how well you are doing while playing the game, something that educational systems lack. The main advantage with video games is that there is nothing to lose from failing, unlike with real-life where failing usually means a bad grade or worse.

There are other games, like Deus Ex: Human Revolution that also provide a model for decision-making skills. The player is forced to think  ahead and contemplate how their actions will affect the future of the game and, more importantly, how they are able to play the game. An ability upgrade enhances the character’s skills and therefore makes it a better option to use that enhanced skill in the future. Also, some games with built-in mini-maps inherently teach people how to read a map. Beyond the North, South, East, and West compass directions, players are taught how to get from point A to point B as fast as possible and how to avoid obstacles like blockages, bodies of water, and enemies.

ahead and contemplate how their actions will affect the future of the game and, more importantly, how they are able to play the game. An ability upgrade enhances the character’s skills and therefore makes it a better option to use that enhanced skill in the future. Also, some games with built-in mini-maps inherently teach people how to read a map. Beyond the North, South, East, and West compass directions, players are taught how to get from point A to point B as fast as possible and how to avoid obstacles like blockages, bodies of water, and enemies.

Criticism

While video games are a constantly growing part of the culture, many people still criticize them for being violent and addictive. The players’ attitudes based on their own experience as users, and how games tend to be an event planned into their everyday lives, contrast with the views of politicians, educational leaders, media professionals and critics. While the number of people who accept video games is growing, the majority still expresses deep concern or just outright rejects them.

This is usually created from their fear of videos causing a growth in violence within the culture. When serious incidents revolving around video game enthusiasts occur, public opinion leaders are quick to pass judgment and disparages against video games all together. Interestingly however, during debates within the United States Senate, many experts have testified that there is a lack of scientific evidence proving the direct links between video games and the negative effects attributed to them.

There is the danger of sacrificing challenge in order to keep the player entertained. Too often, video games can fall into a formulaic level-based structure that is more monotonous than challenging. Also, sometimes people are more concerned with how things look visually than how engaging the content of the game is. No matter how realistic the blood looks, there is still a purpose behind every game.

Video games for an older audience tend to have less obvious educational aspects to it, especially when compared to children’s video games. This is simply because it’s harder to teach older individuals new things. It is indeed a challenge to try and find some educational aspect to some games, but it can be rewarding once it is found. However, the games mentioned earlier, “Minecraft” and “Portal” do provide obvious educational elements, and they are for an older audience.

Video games for an older audience tend to have less obvious educational aspects to it, especially when compared to children’s video games. This is simply because it’s harder to teach older individuals new things. It is indeed a challenge to try and find some educational aspect to some games, but it can be rewarding once it is found. However, the games mentioned earlier, “Minecraft” and “Portal” do provide obvious educational elements, and they are for an older audience.

The main problem with the criticism of video games is the age of the culture around them. Video games have the major following of the young people in the world, which includes every one of the age 35 and below. As such the general majority of officials and political leaders have never played video games. This lack of personal experience along with the caution officials treat the product and marketing of the entertainment industry, has most likely contributed to the social discourse of all the games, platforms and gamers. But like all new entertainment mediums, they will always be defined by their users, no matter how diverse it might appear to be.

world, which includes every one of the age 35 and below. As such the general majority of officials and political leaders have never played video games. This lack of personal experience along with the caution officials treat the product and marketing of the entertainment industry, has most likely contributed to the social discourse of all the games, platforms and gamers. But like all new entertainment mediums, they will always be defined by their users, no matter how diverse it might appear to be.

Video games are seen as a weapon of destruction, but they can also be viewed as an “important tool for teaching complex principles.” For years we have all believed that video games are bad for children. However, those accusations can be attributed to the historical events that have occurred in the US over the years. The shooting at Columbine painted a negative image in the minds of adults.

POPULAR EDUCATIONAL GAMES FOR CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

Big Brain Academy: Wii Degree

ClickN READ Phonics – Beginning Reading

ClickN SPELL – Beginning Spelling

Carmen Sandiego (series)

The ClueFinders

Dr. Kawashima’s Brain Training (a series of two games)

EcoQuest (a series of two games)

GCompris (GPL)

Genomics Digital Lab

Gizmos and Gadgets

History of Biology Game

Immune Attack

Inanimate Alice

InLiving

I.M. Meen

JumpStart

Learnalot

Math Blaster