eLearning Technology in the Classroom

This article is an abstract from SSU EDUC 571, Dr. Paula Lane, Capstone Research Assignment

Education Technology

What is education technology? Quite simply it’s the use of technology to educate. Not to be confused with technology education, which teaches the use of technology, education technology is the infrastructure, both hardware and software, that’s used in today’s modern classroom to facilitate the education of students. This included both in class (synchronistic) and distance (asynchronistic) learning.

Any technology cannot be understood apart from the patterns of its use. At first, people thought only of using new technologies for already well-established social purposes. Soon, the interaction of people and technology created new social practices—the telephone, for example, broke down long-established boundaries between the private world of the family and the public world of the community. Examining that moment in history invites us to consider the roles of technologies in public schools today, at a time when digital technologies are still new in teaching and learning and the patterns of their use still tentative and unsettled. (Maloy, R. W., et al 2010) p. 81)

Technology should be an everyday tool supporting curricular goals and teachers need to be clear about the fact that they are not “teaching technology.” The best courseware, software designed for educational program use, promotes understanding of curricular concepts and standards and is research-based. Computer-based technology in K-12 education should be used as a means to achieve learning goals and not as goal in itself. Technology is most powerful when students and teachers take advantage of its sophistication and versatility to support higher-order thinking and conceptualizing (Ringstaf, et al., (2002) Pg. 1). Technology also has the ability to enhance administrative, teacher and student capabilities and performance, especially for those students who lack access to technology outside of school (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg.1).

The role of computer and communication technology in education has combined to create a revolution that has touched every aspect of our homes, workplaces, and schools. Technology not only allows us to do old jobs in new ways, but also can be used to do things in education that were until now impossible. We have now the opportunity to use technology in ways that are devoted to the premise that all K-12 students are capable of learning, even using different pathways. The effective use of technology in education requires the time needed to develop and refine strategies until they are proven to work. The key technological element of the past fifty years has been the exponential growth of our access to information. (Thornburg, D. D., 1999).

The role of computer and communication technology in education has combined to create a revolution that has touched every aspect of our homes, workplaces, and schools. Technology not only allows us to do old jobs in new ways, but also can be used to do things in education that were until now impossible. We have now the opportunity to use technology in ways that are devoted to the premise that all K-12 students are capable of learning, even using different pathways. The effective use of technology in education requires the time needed to develop and refine strategies until they are proven to work. The key technological element of the past fifty years has been the exponential growth of our access to information. (Thornburg, D. D., 1999).

Teachers and students are only beginning to realize how new technologies can transform education. Rapid access to information online creates never-before-possible teaching and learning opportunities. People in every K-12 school can view, hear, and read materials that were previously only available to scholars. Sooner than expected, every teacher and student will be able to be an e-teacher and an e-student, learning with combinations of paper and electronic materials (Maloy, R. W., et al 2010 p. 67. However, many entrepreneurs in K-12 believe technology can solve all education’s problems, but don’t work to understand those problems before prescribing technology to solve them. That frustrates educators and can be a recipe for failure for fledgling K=12 companies (Tomassini, J., 2012 Pg. 1).

If we are to achieve the one of the primary goals of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB), that is, by eighth grade all students should be technologically literate and to make technology an important source of support for teaching and learning across the curriculum seven key recommendations have to be met:

1. Improve access, connectivity, and requisite infrastructure;

2. Create more high-quality content and software;

3. Provide more sustained, high-quality professional development and overall support for teachers seeking to innovate and grow in this domain;

4. Increase funding from multiple sources for a range of relevant activities;

5. Define and promote the roles of multiple stakeholders, including the public and private sectors;

6. Increase and diversify research, evaluation, and assessment; and

7. Review, revise, and update regulations and policy that affect in-school use of technology, particularly regarding privacy and security.

Educational technology has evolved from the stand-alone computers of the 1980s, to the networked, multimedia workstations of the 1990s, to the highly portable and wireless devices that are everywhere today. Accordingly, educators’ view of how technology can and should be used have also changed in response both to the evolving priorities of the education community and the ever-changing capacities of technology.

Culp, K., et al. (2005) P. 305.

Classroom Hardware

Technology resources must be sufficient and accessible. Success depends on students and teachers having enough computers as well as convenient, consistent, and frequent access to them. Past research suggests that near-universal access is possible with one computer for every five students a ratio far exceeding that found in most classrooms, especially those serving poor and minority students. Often, computers are in labs rather than classrooms, a situation that impedes access (including student and teacher access to the Internet) and limits achievement impact. Today the goal is classroom “one-to-one” attainment, a digital devise for every student.

Rising numbers of schools are joining programs that explore the use of handheld computing devices, in part because their lower cost may help narrow the gap between the digital “haves” and “have-nots.” The portability of these devices and/or the use of laptop computers can enable every student to use computers, including the Internet, for homework. That, in turn, can boost achievement.” The key to this result is for teachers to give meaningful, engaging assignments, rather than busywork. (Ringstaf, et al., (2002) Pg. 1).

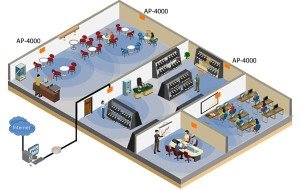

Technology funding should be contingent on districts’ demonstrating that an adequate student-to-computer ratio is part of their plan. State policy should address the digital divide, ensuring adequate technology resources for all students, including after-school access to computers for students who don’t have them at home. Plans should include sufficient resources for new equipment or, if donated equipment must be used, should outline minimum standards for it. Computers should be in classrooms rather than labs so that they are routine learning tools. Internet connectivity is essential. (Ringstaf, et al., (2002) Pg. 1).

Technology spending decisions need to be based on up-front planning that integrates technology use into a cohesive strategy aimed at supporting learning goals. Equipment and use decisions need to be goal-oriented (What student skills, capabilities are you striving to develop? Will this technology help bring home and school closer together?), research-based (What evidence supports using this technology?), and realistically funded (have you budgeted for ongoing maintenance, replacement and for teacher training and at-the-ready technical support?) (Ringstaf, et al., (2002) Pg. 1).

In a study conducted by the international Society of Technology in Education, teachers reported using an abundance of hardware, and, although software use varied considerably, uses of traditional applications were more common. More than half the inquiries reported using more than nine classroom computers (56%), whereas less than 10% reported using three or fewer computers. Nearly 25% reported computer lab use or one-to-one access. Word processing (63%) and presentation tools (61%) were the most commonly used productivity tools, whereas authoring tools (12%) and databases (7%) were the least commonly used. Teachers reported using digital video (34%), digital audio (41%), draw and paint programs (31%), and concept mapping software (26%) in many of the inquiries. Eighty-three percent (83%) of the inquiries used Internet browsers, whereas 20% used Web 2.0 tools and 12% did not use the Internet (Dawson, K. 2012 p. 120).

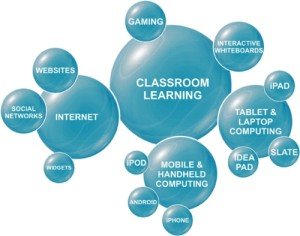

Technological hardware in the K-12 classroom is fast evolving from using computers for drill-and-practice, word processing and as calculators into a tool for facilitating as vast array of learner inquiry. Barab, S. A., et al. (1998) P.15). The primary electronic devices in schools are still desktop and laptop computers, however, newer devices, designed to take advantage of high speed broadband connectivity in the classroom are starting to emerge.

Technological hardware in the K-12 classroom is fast evolving from using computers for drill-and-practice, word processing and as calculators into a tool for facilitating as vast array of learner inquiry. Barab, S. A., et al. (1998) P.15). The primary electronic devices in schools are still desktop and laptop computers, however, newer devices, designed to take advantage of high speed broadband connectivity in the classroom are starting to emerge.

Several electronic devices have been around awhile but are still invaluable in the K-12 classroom. They include: Portable Storage Devices, also known as “flash drives” or “thumb drives” that are a small hard drive designed to copy/store digital content and are a cost effective way of providing each student with ample space to not only save their work for transport between the classroom and home; There should be at least one wireless connected LaserJet Printer in each classroom so teachers and student can see their work and place “hard-copies” in their binders; Many presentation devices need a Projector in addition to the presentation device itself for classroom display and projectors are essential for the classroom when teachers and students utilize other technology components, such as the interactive white board.

“Technology Tools for Schools Resource Guide” (http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED537540.pdf), developed by The National Association for State Title I Directors (NASTID) and the State Educational Technology Directors Association (SETDA), provides definitions of over 40 key technology components as a glossary for educators. The guide also presents essential implementation and infrastructure considerations that decision makers should think about when implementing technology in schools. Technology enhances administrative, teacher and student capabilities and performance, especially for those students who lack access to technology outside of school (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg.1).

The Guide not only defines a complete array of K-12 classroom devices such as Smartphones, Netbooks, Interactive Whiteboards, Wireless Slates and Document Cameras but also describes the device’s value with examples.

Schools may implement technology in a variety of ways including: Centralized Computing Stations which allows students to work in small groups, conduct independent research, and save their work to individual folders or personal storage devices; Mobile Computing Labs (aka COWs – Computers on Wheels) in which laptops are shared among many teachers and signed-out in advance; One-to-One Computing in which every student in the classroom has access their own computing device (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg.1).

Handheld devices can be used for K-12 formative assessments as scores can be delivered in real-time, and after syncing the device, data can be transferred to a secure web platform that provided tools for analysis and data-driven instructional decision making. In addition, teachers, principals and administrators can access a range of easy-to-read reports designed to deliver the data views educators needed to track progress and understand what resources and strategies are most effective (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 14).

In a 21st century learning environment classrooms are well equipped with computing devices that provide teachers and students access to software, online resources and digital content.

Learning Management Systems

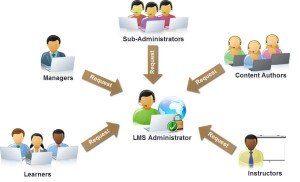

Learning Management Systems (LMS), also known as Instructional Management Systems are online collaboration and communication tools which enable administrators, teachers and students to collaborate and communicate online in real-time across geographic distance. Some of the more popular commercial and open source MLS include Blackboard Learning System, Share-Point LMS, ANGEL Learning Management Suite, Sakai, and Moodle.

LMS combine online course management, communication and collaboration tools which can include a discussion forums, file exchange, email, online journal/blog, real-time chat, interactive whiteboards, bookmarks, calendar, search tool, group work, electronic portfolio, registration integration, hosted services, quizzes/surveys, marking tools/grade book, student tracking, content sharing and object repositories, amongst other tool offerings. (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 8).

Known as the E-Rate Program, the Telecommunications Act of 1996 authorized the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to implement a program to assist schools and libraries in acquiring advanced telecommunication services. Under the program priority is given to supporting request for telecommunication services and Internet access and schools and libraries can receive discounts from vendors on the cost of eligible telecommunications services, Internet access, and internal connections (the equipment needed to deliver these services). The discounts range from 20 to 90 percent, with higher discounts given to applicants in low-income and rural areas. Request for e-rate support have increased steadily from year to year since program funding began in 1998. For the third and fourth program years, total request greatly exceeded the program’s current annual funding cap of $2.25 billion (Czerwinski, S. J., 2001 p.6)

Known as the E-Rate Program, the Telecommunications Act of 1996 authorized the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to implement a program to assist schools and libraries in acquiring advanced telecommunication services. Under the program priority is given to supporting request for telecommunication services and Internet access and schools and libraries can receive discounts from vendors on the cost of eligible telecommunications services, Internet access, and internal connections (the equipment needed to deliver these services). The discounts range from 20 to 90 percent, with higher discounts given to applicants in low-income and rural areas. Request for e-rate support have increased steadily from year to year since program funding began in 1998. For the third and fourth program years, total request greatly exceeded the program’s current annual funding cap of $2.25 billion (Czerwinski, S. J., 2001 p.6)

Because of the Federal Communications Commission action to update the E-rate program, an additional $9 billion will be made available over 10 years to provide 20 million more students with high-speed Wi-Fi in their classrooms and libraries. (Duncan, A. 2014)

Much of LMS is based on mobile wireless technology which is defined as technology that provides continuous accessibility to users anytime, anywhere without using wire or cable to connect to internet networks, transmit data or communicate with others and enable K-12 classrooms to connect to network resources, to exchange email and to use instant messaging. An increasing number of K-12 schools have adopted mobile wireless technology as teaching and learning tools (Kim S, et al, 2005, pg. 58)

To provide students with a range of resources during a 50-minute instruction session, such as share handouts, instructional videos from YouTube, and other course resources, a web-based LMS software package provides self-service and quick (often personalized) access to content in a dynamic environment. Administrative, reporting, and documentation activities are also supported by a LMS (Jensen, L. A. (2010) P. 77).

Chat reference and Web 2.0 RSS feeds can also be included in an LMS and will update information automatically. RSS is an acronym for Really Simple Syndicationand Rich Site Summary. RSS is an XML-based format for content distribution. Webmasters create an RSS file containing headlines and descriptions of specific information. While the majority of RSS feeds currently contain news headlines or breaking information the long term uses of RSS are broad. Consumers use RSS readers and news aggregators to collect and monitor favorite feeds in one centralized program. RSS is becoming increasing popular. The reason is fairly simple. RSS is a free and easy way to promote a site and its content without the need to advertise or create complicated content sharing partnerships.

Improved communications has helped the success of team teaching and mentoring programs which allows teachers to work together within departments and collaborate across subject areas to create best practices multi-discipline lessons. Teachers can now post all needed information on their class webpages to direct students and parent’s questions there. Increased communication between teachers and parents is reflected in the large increase in parents visiting school and classroom webpages. Advanced students moved ahead with accelerated assignments, readings and activities, while those who need extra work to catch up have access to study guides and can ask teachers and other students’ questions through email or online discussions forums. This makes all students’ learning more self-directed (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 8).

Improved communications has helped the success of team teaching and mentoring programs which allows teachers to work together within departments and collaborate across subject areas to create best practices multi-discipline lessons. Teachers can now post all needed information on their class webpages to direct students and parent’s questions there. Increased communication between teachers and parents is reflected in the large increase in parents visiting school and classroom webpages. Advanced students moved ahead with accelerated assignments, readings and activities, while those who need extra work to catch up have access to study guides and can ask teachers and other students’ questions through email or online discussions forums. This makes all students’ learning more self-directed (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 8).

In K12 education, cloud computing holds incredible promise for improving efficiency and reducing costs relating to MLS maintenance and installation, particularly in district administrative functions. As more resources move online into the cloud, the need for constantly upgraded software, computers and local servers rapidly decreases, saving time and money. HP is planning cloud computing pilot programs in several school districts in the coming months. (Dyrli, K. O. 2009, Pg. 32). Now that money also goes further: Web hosting is cheaper; bandwidth is becoming faster; and cloud-based applications, which are run through remote servers instead of costly on-site servers, are now proliferating (Tomassini, J., 2012 Pg. 1).

In addition to equipping classrooms with technology tools and resources, decision makers should take into account other essential implementation and infrastructure considerations including technology planning, IT support and data systems. Integrating technology tools requires comprehensive planning. The International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) provides National Educational Technology Standards for students, teachers and administrators (NETS-S, NETS-T and NETS-A). The ISTE Essential Conditions highlights 14 conditions including planning and leadership, professional development, technical support and policies. In addition, IT support is essential for effective technology implementation. IT support often includes asset management, user administration,software installation and configuration, maintenance, warranties, technical issues, and other issues such as supporting daily technical issues; technical and support liaison with vendors; ensuring that all eligible teachers, administrators and students have a working device; creation and management of account access; and software installation and configuration. (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 11).

At first LMS software was no more than a graphic interface for a policy editor that allowed the administrator to lock users out of specific application or system settings. Today desktop security needs to be the foundation of the overall security plan in K–12 education. Administrations estimates that for every e-mail user on a network, one tech support day per year will be spent dealing with viruses and spyware from e-mail. Today in K–12 schools, with the advent of online testing, the new NETS and data driven decision-making, the computer is no longer a luxury item, but is as much of a tool as paper and pen (Huber, J. (2005) P. 58).

Other programs that are associated an LMS platforms are Web Conferencing, Online Editing Tools, Wikis, Geographic Information Systems, Podcasting, Webcam, Student Response Systems, Social Bookmarking, Video-Conferencing, Education Portals, Productivity Tools (word-processing and spreadsheet suites of software products) and any other necessary district specific applications. (Note: Virtual learning and video-conferencing are not the same thing).

The expansion of broadband, high-speed internet has enabled the development of LMS resources. These resources in turn have allowed the proliferation of online learning content which we will now examine.

Online Learning

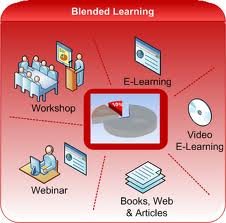

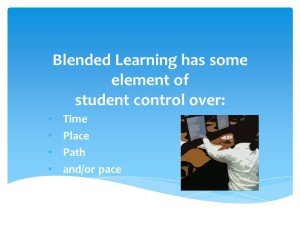

Also known as virtual learning, online learning involve both synchronous and/or asynchronous instruction and is supplementing the bricks and mortar traditional school approach to education (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 11). This duel learning model is commonly known as “Blended-based learning.”

Online learning programs can provide vast opportunities for students and teachers that may not otherwise be available locally. Online learning supports equity and access for students, including highly qualified teachers, flexible learning opportunities, and credit recovery/remediation. Online programs can also provide access to advanced placement, dual credit, and core courses, as well as elective enrichment materials and other courses necessary to meet advanced diploma requirements. Courses are taught by certified and highly qualified teachers, aligned to state standards and delivered through online media using a web-based system (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 11).

Online learning programs can provide vast opportunities for students and teachers that may not otherwise be available locally. Online learning supports equity and access for students, including highly qualified teachers, flexible learning opportunities, and credit recovery/remediation. Online programs can also provide access to advanced placement, dual credit, and core courses, as well as elective enrichment materials and other courses necessary to meet advanced diploma requirements. Courses are taught by certified and highly qualified teachers, aligned to state standards and delivered through online media using a web-based system (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 11).

Currently, there is an increasing number of educators abandoning predominantly lecture-based methods of instruction and moving towards more learner-centered models in which students, frequently in collaboration with peers, are engaged in problem solving and inquiry. This movement is facilitated by current technologies that function less like books, films, or journals and more like laboratories, workshops, and studios where students can immerse themselves within contexts that challenge and extend their understandings. These novel technologies facilitate the development of rich learning environments that encourage exploration and discovery, supporting students in the construction of personally meaningful and conceptually functional understandings (Barab, S. A., et al. 1998 P.15).

Virtual school programs, especially online high school courses, are growing in school districts around the country. According to a report issued in November 2011 by the National Center for Education Statistics, 55 percent of the more than 2,000 school districts surveyed had students in distance education programs during the 2009-2010 school year. The number of students enrolled in individual online courses, meanwhile, multiplied to 1,816,400, compared to fewer than 50,000 a decade earlier. These students, almost three-quarters of whom are high schoolers, are taking a wide range of courses including AP offerings and courses unavailable at their local high schools and credit recovery courses that can remediate failing grades. In addition, it’s not just the large state, nonprofit and for-profit organizations, districts and even individual schools are now starting virtual schools of their own (Schachter, R. 2012. P. 72).

Not only are more districts launching online courses but the definition of virtual schooling also has expanded. That includes the growing popularity of “flipped and blended classrooms,” in which students go online for video lectures and demonstrations outside of class and spend class time working with their teachers individually or in groups. Also, the burgeoning “bring your own device” movement in many districts has brought online learning into the classroom, as students search Web sites for information, collaborate virtually, or work on interactive exercises under the direction of their classroom teachers (Schachter, R. 2012. P. 74).

Not only are more districts launching online courses but the definition of virtual schooling also has expanded. That includes the growing popularity of “flipped and blended classrooms,” in which students go online for video lectures and demonstrations outside of class and spend class time working with their teachers individually or in groups. Also, the burgeoning “bring your own device” movement in many districts has brought online learning into the classroom, as students search Web sites for information, collaborate virtually, or work on interactive exercises under the direction of their classroom teachers (Schachter, R. 2012. P. 74).

In a knowledge economy that values creativity and innovation, software and other tools that allow students and teachers to access and use content should be paired with software and other tools that allow students to create and share content that they develop. Providing students and teachers with the ability to create and control their own content has been effective in increasing student achievement, teacher effectiveness and student pride in their work (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 5).

Online learning technology allows learners to study various phenomena through the participation in activities from which specific concepts emerge. The power of providing learners with rich experiences in an online context where they can engage in activities and observe the results is central to the situated which has guided much of our research. The benefit of these technological tools is that they provide the learner with a host of virtual “experiences” that contextualize and provide legitimacy to learning (Barab, S. A., et al. 1998 P.15).

Digital textbooks offer various interactive functions and provide the learner with a combination of textbooks, reference books, workbooks, dictionaries and multimedia contents such as video clips, animations and virtual reality, both at school and at home without the constraints of time and space. Digital textbooks can save on costs over the long term (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 5). Educational software products (also known as courseware) and subscriptions are available for purchase, download or distribution via electronic media for teachers and students. Many of these products are available for students to use at school and at home (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg.6).

Online Learning Tools

The technology that supports online learning should not be an ad-on but an everyday tool supporting curricular goals something teachers need to be clear about (i.e., they are not “teaching technology”). Similarly, the best courseware is research-based, reflects curricular standards and promotes understanding of concepts and standards. (Ringstaf, et al., (2002) Pg. 6)

Online learning programs are designed to bring the world to the geographically isolated, culturally limited and high poverty students through the use of Mobile Interactive Video Conferencing (MIVC) equipment. Teachers are able to invite in experts from around the world to enter their classrooms as co-teachers, as well as connect their students to students around the globe (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 11).

Wikis are web pages that can be easily edited by multiple authors. They invite active involvement by teachers and students who collaborate in new roles as authors, editors, and readers of academic content. Given the emergence of wikis in business and communications, teachers are considering ways to use this technology to engage students, promote education, and address the demands of curriculum standards and high-stakes achievement tests. They include Web links that can be embedded throughout the pages that connect readers to online academic resources, educational websites, and Internet-based learning experiences including Copyright-free photographs, pictures, and moving images related to different topics (Maloy, R. W., et al 2010 p. 69).

Online learning has fostered the growth of Simulations which is the imitation of a real event or process that can be used to show the real effects of alternative conditions and courses of action. They develop critical thinking skills and strategies and eliminate science lab costs and set up time. Computer simulations of dissections and labs for K-12 education software engage students with immersive and interactive 3-D, audio narration and captioned text of anatomy and physiology (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 11).

The Interactive White Boards (IWB) has become one of the more productive medias for online learning. IWBs are a large display board that comes with accompanying software and connects to an interactive computer and projector. Displayed by the projector onto the IWB, the computer’s desktop is controlled by the teachers and students touching the IWB using a pen, finger, tablet or remote control. The ability to touch varies. Some IWB software tools record and save lessons that can be viewed by students who missed a class or by students who need repetition and review. Interactive whiteboard software (also known as collaborative learning software) allows teachers to create, deliver and manage lessons within a single application (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg.3).

The use of Blogs is an important feature in online learning. They can be used in various ways such as by students to respond to their assignments, write social posts, report on activities and events, support one another, and express feelings and emotions. Although the objective of many distance-learning initiatives may be to increase learning opportunities for spatially distant learners, the use of technology may lead to feelings of isolation and alienation. In web-based learning environments blogs can help bridge learners and reduce feelings of alienation. Understanding learner perceptions may contribute to and enhance the effectiveness of the design of distance learning (Dickey, M., 2004 p. 286)

Positive Online Learning Experiences

Research regarding the effects of online learning is now starting to emerge. Some of the positive experiences K-12 schools have experienced using online learning tools:

At Kulm High School in North Dakota handheld computers and software has allowed teachers to interact with every student in the room at the same time by creating a “Chat Room” like environment within the actual classroom. Teachers and students interacted via the handhelds throughout the school day. Teachers were able to push out assignments and collect assignments electronically. The administration reported that discipline was better; grades were higher; and students were retaining what was taught, according to the scores on the state assessment and online assessments that were conducted twice during the year (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 8).

In 1997 a study called Technology Enhancing Achievement in Middle School Instruction (TEAMS), assessed how effective was online education in Maryland middle schools. At two of the three schools where the evaluation took place, improvements (from fifth grade to sixth grade in the standardized test performance of TEAM students were compared to improvements among students in a comparison group. Student scores on the overall test, as well as on the mathematics and language portions, were examined. At the middle school where TEAMS has been in place the longest, TEAMS students improved their scores the most. Most students had a positive experience and the teacher agreed. Students rated themselves high on self-directed learning. Most students indicated that they liked working in small groups and felt they learned while working in them. Students gave themselves high ratings in computer skills, a set of skills that Project TEAMS is designed to foster online learning (Reiser, R.A., et al 1998 p. 43).

In 1997 a study called Technology Enhancing Achievement in Middle School Instruction (TEAMS), assessed how effective was online education in Maryland middle schools. At two of the three schools where the evaluation took place, improvements (from fifth grade to sixth grade in the standardized test performance of TEAM students were compared to improvements among students in a comparison group. Student scores on the overall test, as well as on the mathematics and language portions, were examined. At the middle school where TEAMS has been in place the longest, TEAMS students improved their scores the most. Most students had a positive experience and the teacher agreed. Students rated themselves high on self-directed learning. Most students indicated that they liked working in small groups and felt they learned while working in them. Students gave themselves high ratings in computer skills, a set of skills that Project TEAMS is designed to foster online learning (Reiser, R.A., et al 1998 p. 43).

In Upper Saddle River School District, NJ, “Poetry Podcast” project, second grade students created a class Podcast of their poetry reading. Using the Reading and Writing Workshop model as its backbone, the second graders read and wrote poetry for a unit lasting four to six weeks. Since implementing the program in 2005, student vocabulary scores have increased by 9.3% and Reading Comprehension scores have increased by 3.2% (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 6).

Using online learning Fruitdale Elementary School in Oregon, fifth grade Reading/Lit Statewide Standards Assessment scores rose from 61.4% in 2006/2007 to 95% 2007/2008. In math, 86.7% of students met or exceeded in 2007/2008, up from 63.6% in 2006/2007. Gains were also noted at other elementary, middle and high schools (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 10).

Research results from the TI MathForward program, a program that extensively uses Graphing Calculator-based Learning response devices, has shown that participating students have demonstrated significant achievement gains on state mathematics assessments and has helped close the achievement gap for African American students (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 4).

As part of the curriculum project in Webster Parish Schools, Louisiana, two schools were provided with Webcams for classroom integration activities. Both public schools involved in the grant reflect growth in school improvement scores and students, teachers, and administrators reflect growth in technology proficiency as measured by the Louisiana Technology Proficiency Self-Assessment (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 5).

Maine’s Learning Technology Initiative (MLTI) provides one Laptop per student and teacher in all middle and high schools in the state and provides teacher and administrator professional development and technical support. Academic achievement results included increase in writing standard from 29% to 41.4% (after year 4). Also, economically disadvantaged students outperformed economically advantaged students in some situations. (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg.1).

A meta-analysis of the effects of computer technology on school students’ mathematics learning was conducted to examine the impact of Computer Technology (CT) on mathematics achievement for students in grades K-12. Based on a total of 85 independent findings extracted from 46 primary CT studies involving 36,793 learners, overall positive effects were found on mathematics achievement. On average, there was a moderate but significantly positive effect on mathematics achievement which indicates that in general students learning mathematics with the use of CT, compared to those without CT, had higher mathematics achievement (Qing, L., et al 2010) p. 242).

In Adams, Helms and DeJean school districts in California as part of an initiative to increase math scores through the use of technology, classes were provided Digital Cameras and when some students experienced difficulty with complicated algebraic curves, known as parabolas, teachers photographed those they saw in nearby architecture. Students imported the digital pictures into computer programs to graph the parabolas and then went off-campus to find and photograph their own examples. The students gained a much deeper understanding of that concept, teachers were energized, test scores improved and dropout rates decreased (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 2).

In Adams, Helms and DeJean school districts in California as part of an initiative to increase math scores through the use of technology, classes were provided Digital Cameras and when some students experienced difficulty with complicated algebraic curves, known as parabolas, teachers photographed those they saw in nearby architecture. Students imported the digital pictures into computer programs to graph the parabolas and then went off-campus to find and photograph their own examples. The students gained a much deeper understanding of that concept, teachers were energized, test scores improved and dropout rates decreased (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 2).

A research review by the British Educational Communications and Technology Agency shows that Interactive White Boards in the classroom increased student engagement and motivation; allowed greater opportunities for participation and collaboration; improved personal and social skills and self-confidence; provided greater progress in mathematics and science; accommodated different learning styles; and improved learning for special needs students (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 3).

In Lincoln Elementary, Mt. Lebanon School District, PA chapter tests were used to assess the impact of the Interactive White Board, student responses systems, and interactive software on student learning in Math. In classes where the interactive white board and student response systems were used, average test scores were more frequently higher when compared to the other classes (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 3).

Online Learning Negative Experiences

An EU study was conducted on integrating a particular Network Collaborative Technology into a secondary school history-geography classroom for debates on sustainable development. This work was to develop pedagogical and software tools for small-group discussions in the classroom, where students could discuss at the same time face-to-face and via the network. Students were asked to debate questions such as “should production of genetically modified organisms be allowed in France.” This attempted CSCL technology integration failed in that pedagogical objective of the teaching sequence (elaborating knowledge of societal debates) was never achieved. The planned teaching sequence had to be continually modified in the light of failure of preceding phases and the study was abandoned before its planned end when the classroom degenerated into chaos and threats of physical violence between some students (Baker, M. M., et al 2012 p. 172).

Online Learning Administration

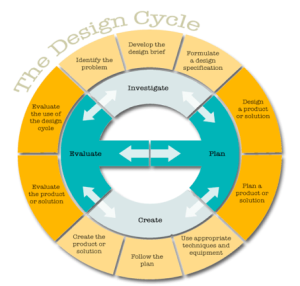

Implementing online programs requires attention to critical areas such as administration, quality control, learning management systems and teacher training. One of the biggest problems is trying to take face-to-face classroom learning and putting it online. Online environments require different pedagogy designs and expectations. Online courses can’t just be developed, uploaded, and taught. They have to be developed by professional web and instructional designers who understood online course design. In addition, all teachers don’t make good online teachers as the skill set is different (Schachter, R. 2012. p. 76).

If new online programs aren’t designed properly they can have different looks and be confusing to teachers and students. The content and assignments should be developed on standardized templates with ways to tract the assignments. Also completion schedules and pace charts should be designed to be flexible to accommodate the various skills and learning styles of the students.

Once the online programs have been piloted and implemented it is important that each school have its own councilor dedicated to the online programs who is responsible for student/parent interface with weekly newsletters containing information about the programs such as what to expect of online learning, from homework to the role of the teacher. (Schachter, R. 2012. p. 78).

Many school districts, although in various states of flux, now have enough online courses, such as creative writing, biology, geometry and AP government, for students to earn a high school diploma which will help the districts reach a growing population of homeschoolers, as well as students in other districts. In order to administer these programs classroom teachers needed additional course support such as Flash segments on various contentment areas and additional Wi-Fi capacity including more access points, bandwidth and switches that will prioritize prompt access to virtual course content to avoid student disengagement. (Schachter, R. 2012. Pg. 79)

Online Learning Program Development

The difficulty of selling online learning products to schools is a common refrain among the education technology companies. Many purchasing decisions are made by people who are not the products’ end users which are the teachers. The sales process can be slow and tanged with politics, and because authority often rests with local agencies, there are, in many ways, different markets for each of the 50 states, or even for each of the roughly 14,000 school districts. Every person in education technology development is trying to find a way to make money without selling to schools. The alternative is selling to teachers, parents, and students, which some Imagine K12 companies intend to do. (Tomassini, J., 2012 Pg. 1).

Typically, new products in education require extensive research costly focus groups, and lengthy sales cycles that prevent innovation. Imagine K12’s partners believe. In the new technological climate, teachers can test products through the Web, and they’re directly reachable by cell phone, Skype, Facebook, and Google Chat. They believe teachers should be a larger part of the software-development process (Tomassini, J., 2012 Pg. 1).

Digital Citizenship

With the huge amount of information and multimedia flowing through our schools and home Digital Citizenship has become an important topic when considering student and teacher’s use of technology in both personal and educational settings. Kids today have access to media and  information anytime and anywhere. Therefore, learning does not happen only eight hours a day within the school building as it did for a majority of students in past generations. Access to technology poses many opportunities to develop life-long learners with creative, innovative approaches to solving problems now and in the future. It also poses challenges as schools struggle to stay ahead of this ever-changing landscape. States and districts are attempting to develop standards and policies that will keep students safe by providing them with technology skills and utilizing communication and information in the most productive ways (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 123). CodeHS is an online computer-science curriculum designed to help teachers and students develop better programming skills and, ultimately, become more modern citizens. (Tomassini, J., 2012 Pg. 1).

information anytime and anywhere. Therefore, learning does not happen only eight hours a day within the school building as it did for a majority of students in past generations. Access to technology poses many opportunities to develop life-long learners with creative, innovative approaches to solving problems now and in the future. It also poses challenges as schools struggle to stay ahead of this ever-changing landscape. States and districts are attempting to develop standards and policies that will keep students safe by providing them with technology skills and utilizing communication and information in the most productive ways (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 123). CodeHS is an online computer-science curriculum designed to help teachers and students develop better programming skills and, ultimately, become more modern citizens. (Tomassini, J., 2012 Pg. 1).

Online student Assessments

Online learning also means Online Student Assessments. Online assessments can be used through secure network connections to assess student understanding of content regardless of the delivery methodology. Online assessments are used for testing to provide feedback to the student or teacher. Data in can be used for student grade promotion and, in some cases, for facilitation of state standardized achievement tests and real-time, automated scoring and aggregation of results can be analyzed in a timely fashion. Online versions of tests are exactly the same as paper-pencil versions with the only difference being the format. The administrative benefits that can be gained from online assessments include less administrative time required to record student demographic data; improved test monitoring capabilities; web-based reporting of student test results; and reduced turnaround time to receive student test scores thus increasing instructional time (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg.14).

Education Technology Professional Development

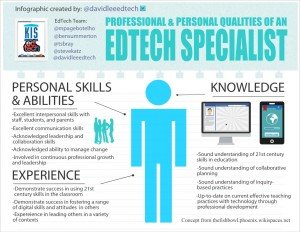

Nearly every article antedated for this paper stressed the fact that the most important aspect of effective online learning is dependent on knowledgeable, creative and flexible teachers. In this section we will look at online learning education technology teacher training and the use of that technology to also train online learning teachers.

The challenges to train teachers are many.In some cities, K-12 schools have children from as many as a hundred different language groups and cultures. In addition, race, religion, sex, economic background, and age impact student preparation, ability, and motivation. The variations are unending. Accordingly, there no professional preparatory program that can encompass every population let alone every eventuality. There are dozens of aspects and variables to teaching.

It is important to note that the technology is not the total experience; rather it is a tool or resource with the potential to support learners who are engaging in a diverse learning experience. The potential of any education technology is dependent on the presence of a teacher/facilitator who helps the learner establish and appreciate the technology in relation to the greater context in which it is situated. The role of this teacher/facilitator is not to tell students right answers and correct procedures, but rather to guide students as they direct their own learning process. In other words, technology is simply a tool that teachers can use to aid in the development of robust learning experiences for students. However, we believe that within the proper context emergent technologies can serve as a flexible tool for supporting learning and holds exciting promise for educators (Barab, S. A., 1998) p.22).

Improved Teacher Training

Nearly one-third of virtual high school teachers are not qualified to teaching online, falling short in areas such as building an online community, developing thoughtful questions that could be discussed asynchronously by students, and pacing their courses. One of the problems is that schools don’t have the tools to select teachers properly. Some of the questions that should be asked when hiring virtual teachers are: “How much do you incorporate project-based learning;” “How do you use collaborative student groups in the classroom;” and “How do you divide project time among areas such as direct instruction, student research and student collaboration.”

Because teachers differed widely in their approaches and effectiveness codifying what is expected of online teachers can help alleviate these differences. Some expectations included having student collaborate with one another and choosing the materials with which to best collaborate, which in turn became the basis for evaluating the teachers’ courses and performance.

Because teachers differed widely in their approaches and effectiveness codifying what is expected of online teachers can help alleviate these differences. Some expectations included having student collaborate with one another and choosing the materials with which to best collaborate, which in turn became the basis for evaluating the teachers’ courses and performance.

One way of improving online pedagogy is to have a six- to eight-week online course required of all teachers. Such a course was devised by a team of instructional and Web design consultants. Known as NetCourse instructional Methodologies, the course is available for graduate credit and demands 10 hours a week. It focuses on developing techniques to stimulate and moderate student’s discussion online, building activities that require students to collaborate with each other, and setting online courses in the standardized template.

The secret in any type of education is the support the teacher gives the student, and to do that, the teachers have to get training. The less formal approach has given way to a one-week orientation for new teachers every summer before the new school year. Thoseteachers also are assigned a mentor for that year, and they continue their studies through a series of webinars. (Schachter, R. 2012. Pg. 76)

Experts suggest a 30/70 rule: Spend 30 percent of the technology budget on equipment and 70 percent on the supportive “human infrastructure.” By contrast, most school districts spend less than 10 percent on teacher training (Ringstaf, et al., (2002) Pg. 12).

On-going sustainable professional development is an essential for creating 21st century learning environments and changing the way teachers teach and students learn. Professional development options may include: Education Portals; Online Courseware; Professional Learning Communities; and Technology Coaches/Integration Specialists. Teachers trained in how to use technology use it more often and in ways that result in student gains. Conversely, lack of training is a significant barrier to success. For technology to become a core component of teachers’ instructional repertoire, they not only need familiarity with equipment, but more important they need to see and practice the most productive ways of using it to support learning. They need time to explore, reflect, collaborate with peers, and engage in hands-on learning (Ringstaf, et al., (2002) Pg. 12).

Online Courseware provides teachers access to online courses. Online courses provide professional development resources for teachers in all districts, regardless of geographic location. Teachers have access to several clusters of courses. In one cluster, teachers learn what types of curricula and learning principles ensure students’ success in the 21st century workplace and post-secondary education. In another cluster, teachers receive the skills and knowledge necessary to implement technology in the classroom through web-enhanced lessons, project-based learning, and virtual field trips. Teachers can connect with other teachers in an online environment to ensure on-going and sustainable professional development (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg.14).

Professional Online Learning Communities provide teachers and administrators the opportunity to share resources, highlight strengths and gain support in an online setting. They provide the opportunity for collaboration in a collegial environment and for teachers to learn and share without time or travel constraints.

For example, Iowa’s Professional Development Model incorporates video conferencing, peer coaching and follow-up assessments and promotes individualized instruction. Teachers and coaches are able to watch others teach using video conferencing despite long distances. (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg.14). Through anonymous surveys in individual online courses, teachers’ opinions were sought on whether online classrooms provided opportunities for successful professional development, especially for online science content courses. What the authors discovered was that teachers are tremendously positive when discussing the value of the online environment for furthering their content knowledge in the subjects they teach (Clary, et al. 2009 p. 38).

Technology Coaches/Integration Specialists: In a professional development context, coaches and mentors provide teachers with leadership for lesson planning and implementation, honing specific teaching strategies, developing and identifying instructional materials and resources and modeling professional discussions about student learning. Experimental studies have proven that mentoring and coaching relationships benefit from the use of technology in many ways. As a result of delivering these services using technology, the coaching and mentoring process is compressed through near-real-time service. This is particularly critical in rural and inner-city areas where these opportunities are often limited. Instructional technology coaches or mentors in schools provide opportunities for collaboration in planning and co-teaching to help teachers utilize new practices and resources (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg.14).

Technology skills should be explicit within teaching standards that articulate what teachers need to know and be able to do. Preservice, in-service, and ongoing professional development policies, then, should incorporate the needed training. Since teacher knowledge is key for success, professional development should account for the lion’s share of the technology budget. A key part of teacher training should be access to model exemplary classrooms where teachers can see the innovations of their more tech-savvy colleagues who fully integrate technology into their curricula (Ringstaf, et al., (2002) Pg. 12).

Technology skills should be explicit within teaching standards that articulate what teachers need to know and be able to do. Preservice, in-service, and ongoing professional development policies, then, should incorporate the needed training. Since teacher knowledge is key for success, professional development should account for the lion’s share of the technology budget. A key part of teacher training should be access to model exemplary classrooms where teachers can see the innovations of their more tech-savvy colleagues who fully integrate technology into their curricula (Ringstaf, et al., (2002) Pg. 12).

Teachers may need to change their beliefs about teaching and learning. Rather than lecture recitation, and seat work, technology use pushes toward an instructional mode of supporting student collaboration, inquiry, problem solving, and interactive learning. The transition to such a different way of teaching requires much time and effort. Research shows that providing teachers with a vision of what’s possible via opportunities to spend time in technology-rich classrooms and observe for themselves the impact on teaching and learning can strongly bolster their motivation to take on the challenge themselves. (Ringstaf, et al., (2002) Pg. 14).

Content-focused Technology Inquiry Groups have proven effective in the providing education technology professional development. Research has proven that teachers learn about technology from participating in inquiry groups. Overall, this research has contributed to emerging knowledge and practice of long term, school-based technology professional development initiatives. The potential educative value of the inquiry approach for teachers’ development has been proven and establishing technology inquiry groups within school-based professional development practices is encouraged. Inquiry groups provide greater access to content experts, data-driven decision-making preparation, and collaboration opportunities with peers in other schools (Hughes, J. E., 2005 p.379)

A common question now is “why is a generation of teachers more knowledgeable about technology than any before it, arriving in classrooms with little understanding of how to teach with it?” School districts say “If colleges of education just better prepared new teachers in technology, we’d be all set, but they’re not doing their job” and teacher colleges say “We’re doing a great job, but then teachers go out into schools and they don’t have access to technology.”

Preservice teachers bring a lot of technical expertise but they still have a lot of pedagogy and content to learn from veteran teachers and teacher colleges need to focus more on the education basics and not just the use of technology. A Smart Board doesn’t teach anything.

At the Curry School of Education Center for Technology and Teacher Education they say a five year program of content and technology instruction is what’s needed. Such a program integrates subject-matter education with teaching expertise, coordinating students’ undergraduate and graduate work. The program has since evolved to include technology as a content area. Teaching students first have to know the content. It’s going to be hard to teach calculus if the teacher doesn’t know calculus. They also need to know the pedagogy associated with that content and the instructional strategies that will be effective. And finally, they need to know the innovation or technology that going to be used (Schaffhausen, D. 2009 p.30)

Student teacher interns, aka preservice teachers, are becoming a useful source of education technology professional development. Findings from a study (Technology Integration Solutions: Preservice Student Interns as Mentors) showed that a technology training program, complimented by student interns (mentors), led to successful teacher technology integration. An introductory training session supported by special education and elementary education student mentors supported teacher use of technology in their teaching, especially for students with disabilities. Similarly, teachers without this support expressed initial comfort but long-term use and an ability to apply initial training to instructional needs became problematic. Teacher responses indicated that they had an increased comfort with the application and appreciation of the student intern mentoring. Because student teacher mentoring programs are relatively new, long-term results of this mentorship program are unknown. However, future training efforts are encouraged and should measure long-term and related benefits for technology integration in the K-12 classroom (Smith S., 2004 p. 55).

Conclusion

Overall, this literature research review showed that the development and use of Education Technology is moving forward at a rapid pace. Every stakeholder at all levels of education believes that education technology is and will advance K-12 pedagogy in a way not seen since the start of the 20th century.

We found that technology should be an everyday tool supporting curricular goals and teachers need to be clear about the fact that they are not “teaching technology.” Accordingly, educators’ view of how technology can and should be used have also changed in response both to the evolving priorities of the education community and the ever-changing capacities of technology.

Technology resources must be sufficient and accessible thus the importance of current technology hardware. Success depends on students and teachers not only having enough computers but also convenient, consistent, and frequent access to them. In a 21st century learning environment classrooms should be well equipped with computing devices that provide teachers and students access to software, online resources and digital content.

We learned that Learning Management Systems (LMS) are online collaboration and communication tools which enable administrators, teachers and students to collaborate and communicate online in real-time across geographic distance. The expansion of broadband, high-speed internet has enabled the development of LMS resources. These resources in turn have allowed the proliferation of online learning content.

Online learning programs can provide vast opportunities for students and teachers that may not otherwise be available locally. Online learning supports equity and access for students, including highly qualified teachers, flexible learning opportunities, and credit recovery/remediation. Implementing online programs requires attention to critical areas such as administration, quality control, learning management systems and teacher training. One of the biggest challenges with online learning is trying to take face-to-face classroom learning and putting it online.

Nearly every article antedated for this paper stressed the fact that the most important aspect of effective online learning is dependent on knowledgeable, creative and flexible teachers. On-going sustainable professional development is an essential for creating 21st century learning environments and changing the way teachers teach and students learn. We learned that a technology training program, complimented by student interns (mentors), led to successful teacher technology integration.

References:

Ringstaf, C. & Keley, L (2002) Investing in Technology: The Learning Return, WestEd, S. A.

Culp, K., Honey, M., & Mandinach, E. (2005). A Retrospective on Twenty Years Of Education Technology Policy. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 32(3), 279-307

Barab, S. A., Hay, K. E., & Duffy, T. (1998). Grounded Constructions and How Technology Can Help. Techtrends, 43(2), 15-23.

Dyrli, K. O. (2009). The Start of a Tech Revolution. District Administration, 45(5), 31-33.

Thornburg, D. D. (1999). Technology in K-12 Education: Envisioning a New Future. In: Forum on Technology in Education: Envisioning the Future. Proceedings (Washington, D.C., December 1-2, 1999); see IR 020 683.

Tomassini, J. (2012). Startup Hopefuls Test Their Ideas With Educators. Education Week, 32(4), 1-21.

Czerwinski, S. J., & General Accounting Office, W. C. (2001). Schools and Libraries Program: Update on E-Rate Funding. Report to the Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, State, the Judiciary, and Related Agencies, Committee on Appropriations, U.S. Senate.

Kim S, Holmes K, Mims C., 2005, Mobile Wireless Technology Use and Implementation: Opening a Dialogue on the New Technologies in Education. Techtrends; 49(3):54-64.

Schachter, R. (2012). Avoiding the Pitfalls of Virtual Schooling. District Administration, 48(6), 74-76.

Baker, M. M., Bernard, F. X., & Dumez-Féroc, I. I. (2012). Integrating computer-supported collaborative learning into the classroom: the anatomy of a failure. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 28(2), 161-176. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2729.2011.00435.x

Maloy, R. W., Poirier, M., & Smith, H. K. (2010). The Making of a History Standards Wiki: Covering, Uncovering, and Discovering Curriculum Frameworks Using a Highly Interactive Technology. History Teacher, 44(1), 67-81.

Dickey, M. (2004). The impact of web-logs (blogs) on student perceptions of isolation and alienation in a web-based distance-learning environment. Open Learning, 19(3), 279-291.

doi:10.1080/0268051042000280138

Reiser, R.A., Butzin, S. M. (1998) Project TEAMS: Technology Enhancing Achievement in Middle School Instruction, Techtrends, Pg. 39-44.

Qing, L., & Xin, M. (2010). A Meta-analysis of the Effects of Computer Technology on School Students’ Mathematics Learning. Educational Psychology Review, 22(3), 215-243. doi:10.1007/s10648-010-9125-8

Hughes, J. E., Kerr, S. P., & Ooms, A. (2005). Content-Focused Technology Inquiry Groups: Cases of Teacher Learning and Technology Integration. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 32(4), 367-379.

Schaffhauser, D. (2009). Which Came First–The Technology or the Pedagogy?. T.H.E. Journal,36(8), 27-32.

Smith S, Smith S. Technology Integration Solutions: Preservice Student Interns as Mentors. Assistive Technology Outcomes and Benefits [serial online]. September 1, 2004;1(1):42-56. Available from: ERIC, Ipswich, MA. Accessed August 8, 2014.

Clary, R. M. & Wandersee, J.H. (2009), CAN TEACHERS LEARN IN AN ONLINE ENVIRONMENT?. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 46(1), 34-38.

Recent Comments