History of Education Technology

This article is an abstract from Dr. Maryanne Berry’s Sonoma State University EDCT 552 Praxis Course

Watching the NY Times timeline “The Evolution of Classroom Technology” was a good look at how far classroom technology has come and what was considered “technology.” The “Hornbook” and the “Pointer” looked more like the tools of corporal punishment rather than teaching aids. The progression of the “Magic Lantern;” to the “iPad” was a great timeline of the “visual” aids used in the classroom. These devices eventually led to the PowerPoint and now on to the Infographic.

Russell’s “A Brief History of Technology in Education” was the narrative for the NY Times “Timeline” graphic. For the most part I would agree with his observation, “Today, most people associate “educational technology” with computers and the Internet,” however in America’s primary and secondary schools educational technology encompasses much more than computers and has roots that extend back several centuries. Blackboards and books are now taken for granted and are assumed to be part of every student’s educational experience. In their day, these “technologies” were viewed as radical and revolutionary teaching and learning tools. (Russell, 2006, p.137)

In 1806, students would use a desktop sandbox to practice the alphabet. After the children had made each of the letters, the monitor smoothed the sand with a flat iron and a new letter was presented” (Gutek, 1986, p. 62). Considered “a new form of education technology” (Russell, 2006, p.137) one of the earliest forms of teaching technology was images that were drawn in the sand.

After going through most of the devices that were presented in the NY Times “Timeline” Russell finishes his article with computers as the most current “new” educational technology by stating, “While there are many more examples of computer-based tools that are used in today’s classrooms, there is no question that computers are the most recent technology that has penetrated the American educational system. However, an important question that remains largely unanswered focuses on how computer use in schools is affecting teaching and learning” (Russell, 2006, p.152). Good question, but since computers offer so much in the way of education, I think computers are the best thing to happen in the classroom since the blackboard.

I want to include the Cuban and Strudler quotes as they put a contemporary spin on the evolution of education technology. “I predict that the slow revolution in technology access, fueled by popular support and continuing as long as there is economic prosperity, will eventually yield exactly what the promoters have sought: every student, like every worker, will eventually have a personal computer. But no fundamental change in teaching practices will occur;” (Larry Cuban – Stanford) and “Nearly the entire field of technology and education is about change in some way. It’s about the dreams of what could be, the realities of what is, and the efforts to whittle away at the gap between the two.” (Neal Strudler – UNLV)

TECHNOLOGY IN EDUCATION

The first American schools were one-room cabins, the mission of which was to produce literate and moral citizens. Students attended school for between one and six months a year and there were few educational tools available. But as increasing numbers of American communities were settled the education system became more firmly established. To aid the learning process, educational technologies, such as slates, hornbooks, blackboards, and books were introduced.

Although technologies like the blackboard and books are now taken for granted and are assumed to be part of every student’s educational experience, these technologies were viewed as radical teaching tools when they were first introduced. Over time, a variety of technologies such as film, radio, television, teaching machines, microcomputers and the Internet have been introduced to schools, each sparking controversy about its usefulness for schooling and effectiveness as a teaching and learning aid.

THE HORNBOOK AND PRINTED BOOKS

Johannes Gutenberg began building a primitive version of the printing press in 1436 and the first Gutenberg Bible was printed in 1455 (de la Mare, 1997). Nearly two centuries later Stephen Dayne brought the first printing press used in the United States (Rubinstein, 1999). However, since they were expensive and were not readily available, books were not commonly used in the early years of American schooling.

In lieu of printed books, American settlers improvised with a device known as the hornbook. Adopted from England, the hornbook was one of the first forms of educational technology used to aid in teaching reading in American schools. A hornbook was “a small, wooden, paddle-shaped instrument. A sheet of paper, with the alphabet, numerals, the Lord’s Prayer, and other reading matter printed on it was pasted upon the blade and the entire implement was covered with sheets of transparent horn” (Good & Teller, 1973, p. 28). The hornbook was a crude, low-cost solution to the American settler’s problem of how to teach children to read without having books available. Although it was useful at the time, the hornbook became obsolete as the cost of printing decreased and texts became more widely available.

Perhaps the most popular early printed book was the New England Primer: Introduced to schools in 1690, the New England Primer was intended to make learning to read more interesting for children. “The New England Primer contained the twenty-four letters of the alphabet, each letter being illustrated with a drawing and a verse to impress it on the child’s mind. The primer also contained various lessons and admonitions for youth, the Lord’s Prayer, and the Ten Commandments.” (Gutek, 1986, p. 10) Historian Paul Leicester Ford estimates that 3 million copies of the New England Primer were printed (Gutek, 1986).

The next generation of written texts included Webster’s first spelling book, followed by the McGuffy Readers. The evolution of these primitive textbooks allowed teachers to follow a predefined sequence of lesson plans that taught students how to read and write. In this way, early books served as a tool that began to standardize the content to which students were exposed.

THE SANDBOX

In 1806, the Lancastrian methodology of schooling was introduced in New York City and with this new method of teaching came a new form of educational technology. Lancaster’s method of education was appealing because a large number of students could be educated for a low cost. This method employed a master teacher as well as “monitors” (more advanced students) to teach large classes of students. The monitors, who had been trained by the master teacher taught groups of approximately twenty students a skill, such as writing. Students would use a sandbox on their desk to practice the alphabet: “White sand overlaid the box and the children traced the letters of the alphabet with their fingers in the sand, the black surface showing through in the form of the letter traced … After the children had made each of the letters, the monitor smoothed the sand with a flat iron and a new letter was presented” (Gutek, 1986, p. 62).

Lancaster chose sandboxes because they were the most economically affordable form of technology available at the time. But by the 1830’s, doubts about the effectiveness of the Lancastrian system surfaced. With the decline of this teaching method, the use of monitors and sandboxes ended. Later the sandboxes would be replaced by individual slates. Although they were more expensive, slates allowed students to practice their writing skills more easily. Erasing chalk from a slate was quicker and cleaner than ironing the surface of the sandbox.

THE BLACKBOARD

While individual slates were used in classrooms during the early 1800s, it was not until 1841 that the classroom chalkboard was first introduced. Shortly thereafter, Horace Mann began encouraging communities to buy chalkboards for their classrooms. By the late 1800s, the chalkboard had become a permanent fixture in most classrooms.

As with many forms of educational technology, learning how to integrate the chalkboard into classroom instruction was not an easy task. As Shade (2001) explains, “When first introduced, the chalkboard went unused for many years until teachers realized that it could be used for whole group instruction. They had to change their thinking from individual slates to classroom slates” (p. 2).

Similar to more modem forms of educational technology, the chalkboard also received praise from community leaders. As an example, Josiah Bumstead, a Springfield Massachusetts councilman, said, “The inventor or introducer of the blackboard deserves to be ranked among the best contributors to learning and science, if not among the greatest benefactors of mankind” (Daniel, 2000, p. 1). Thinking of the blackboard as a revolutionary form of educational technology seems counterintuitive. But it is one of the few types of media that has survived the test of time and is still regularly used in classrooms today.

MAGIC LANTERN

The height of its popularity was around 1870. The predecessor to the slide machine, the magic lantern projected images on glass plates. By the end of World War I, Chicago’s public school system had a collection of some 8,000 lantern slides.

LEAD PENCILS

Around the turn of the 20th century mass produced pencils and paper become readily available, gradually replacing the school slate.

STEREOSCOPE

At the turn of the 20th century, the Keystone View Company began to market stereoscopes. The three dimensional devices, which were popular in home parlors, were sold to schools featuring educational sets containing hundreds of images.

FILM

During the next several decades, the American educational system expanded and became more developed. The price of producing paper and printing books also dropped to levels that enabled paper to replace slates and allowed each child to have his or her own books. But just as books were becoming widely available to students, a new form of educational technology began to emerge, namely film.

The kinetoscope, which is now known as the motion picture, was invented in 1889. Over the next decade, film equipment was developed and refined. And in 1902, Charles Urban of London began exhibiting the first educational films. Among these films were “slow-motion, microscopic, and undersea views” and “such subjects as the growth of plants and the emergence of the butterfly from the chrysalis” (Saettler, 1990, p. 96). In 1911, Thomas Edison also contributed to the use of film in the classroom by producing a series on the American Revolution.

With the rapid growth of American schools, both in terms of the number of schools and the quantity of students attending those schools, there was a pressing need to provide standard, high-quality instruction to large numbers of students. At the time, some proponents believed that using film in classrooms met this important educational need. As an example, Thomas Edison proclaimed, “Books will soon be obsolete in the schools. Scholars will soon be instructed through the eye. It is possible to touch every branch of human knowledge with the motion picture.” (Saettler, 1990, p. 98)

In 1910, enthusiasm for educational films led Rochester New York’s Board of Education to adopt education films for instructional use. Many other public school systems soon followed Rochester’s lead and by 1931 “twenty-five states had units in their departments of education devoted to films and related media” (Cuban, 1986, p. 12). Edison’s prophecy and the public school support for educational film spawned a new and quickly growing industry in America, namely educational film.

As early as 1910, more than 1,000 film titles were catalogued in George Kleine’s Catalogue of Educational Motion Pictures. In 1923 Frank Freeman classified the existing educational films into the following four categories: “(1) the dramatic, either fictional or historical; (2) the anthropological or sociological, differing from the dramatic in that it is not primarily based on a narrative or story; (3) the industrial or commercial, which show the processes of modern industry and commerce; and (4) the scientific, which may be classified into subgroups corresponding to the individual sciences, such as earth science, nature study, etc.” (Saettler, 1990, p. 97).

Despite the explosion of educational films, conflict emerged between the commercial interests and the educational interests of the film industry. Concerns about the financial bottom line led the film industry to develop educational films which some critics claimed lacked content and were more theatrical in nature. In addition, teachers often were not asked for input and guidance in making educational films. As a result, the films frequently did not meet teachers’ needs. Then, in the late 1920s, sound film was introduced.

Although the ability to include sound was a step forward for the film industry, it also contributed to the demise of educational filming. Requiring new and expensive equipment, production of educational sound films became an expensive endeavor. At a time when commercial filming was struggling and educators were questioning the merit of film in classrooms, strong advocacy for educational sound films was lacking.

Although film continued to be widely used by the government for armed forces training, agricultural demonstrations, and public relations, the impact of film in the classroom was minimal. As Cuban (l986) described, “film took up a bare fraction of the instructional day. As a new classroom tool, film may have entered the teacher’s repertoire, but, for any number of reasons, teachers used it hardly at all” (p. 17). According to Cuban, the main reasons for the limited instructional use of film included “teachers’ lack of skills in using equipment and film, cost of films, equipment and upkeep, inaccessibility of equipment when it is needed and finding and fitting the right film to the class” (p. 18).

RADIO

Radio entered the educational system in the early 1920s. Like the early days of film, radio was heralded as a tool that would revolutionize classroom teaching. Similar to the proclamations of Thomas Edison regarding film, William Levenson, the author of Teaching through Radio, predicted, “The time may come when a portable radio receiver will be as common in the classroom as is the blackboard. Radio instruction will be integrated into school life as an accepted educational medium.” (Cuban, 1986, p. 24)

In 1923 Haaren High School in New York City became the first public school to use the radio in classroom teaching. Following a decision by the Radio Division of the U.S. Department of Commerce to license time from commercial stations to broadcast educational lessons, many more schools and districts bought equipment and made plans to use the radio in classrooms. Falling equipment prices in the 1930s further increased interest in the instructional use of radio.

Typically, educational radio programs lasted between 30-60 minutes and were broadcasted a few times a week. The limited amount of broadcast time “destined radio usage to be viewed as a supplement to teacher instruction.” (Cuban, 1986, p. 22) Nonetheless, a wide range of radio lessons were readily available to teachers. “There were broadcasts for elementary school listeners and for secondary-school students. There were dramatic re-creations of American history, challenging interpretations of American folk music, delightful dramatizations of children’s stories and legends. There were, in short, a variety and a wealth of curricular material on the air.” (Woelfel & Tyler, 1945, p. 42)

Two survey studies conducted in 1941, one in Ohio and one in California found that the majority of schools had radio receivers. Moreover, the amount of radio hardware available to teachers in the 1930s and 1940s exceeded the amount of film hardware available at the height of film use.

Higher education was also impacted by the invention of the radio. Some colleges and universities established their own radio stations for instructional use. Ohio State University first began broadcasting weather reports in 1912. But the radio was not used for instructional use in higher education until the 1920s, when “schools of the air” were formed. These radio-based schools partnered with a local radio station, developed curriculum, created lesson leaflets, produced educational programs, established a weekly schedule for broadcasts, trained staff, and ultimately executed the concept of “schools of the air.”

Educational technology zealots initially dreamed of the radio replacing both schools and teachers. But by the end of the 1940s, funding and educators enthusiasm for radio use diminished significantly. Saettler identified problems with equipment and support as two factors that limited instructional use of radio. In addition, Saettler (1990) found that schools “fail to use (the radio) properly or integrate its programming with the school curriculum” (p. 197).

Similar to problems encountered by educational films, another factor that contributed to the downfall of educational radio was the struggle between commercial stations and educators. A 1925 decision by Herbert Hoover, who was then Secretary of Commerce, to leave radio in the hands of American business, instead of having it controlled by the government made efforts to keep educational radio alive exceedingly difficult. Unable to conduct a unified fight to maintain a presence on radio stations, educational interests in radio were overpowered by the commercial radio stations united fight against educational radio. “The networks maintained that allocating frequencies for educational broadcasting would only disrupt a successful system of broadcasting that had just begun to function well.” (Saettler, 1990, p. 203) As a result, educational radio languished as the big business of commercial radio boomed.

By the end of the 1940s, technology proponents had given up on educational radio and instead began focusing on the use of television in schools, which was perceived to be the ultimate combination of audio and visual technology.

OVERHEAD PROJECTOR

In the 1930’s the overhead projector was widely used by the U. S. Military to train forces during World War II and eventually the device spread to schools.

THE TYPEWRITER

An often overlooked form of educational technology, the typewriter is the one form of mechanical technology that has penetrated and been used by large numbers of students over several decades. This use, however, has generally been limited to “business” classes that focus specifically on teaching students how to type. While typewriters were present in most high schools into the 1990s, they have been absent from the majority of classrooms and not used widely throughout a student’s educational experience. However, there are close parallels between the typewriter and more modem forms of computer-based technologies.

The first functioning typewriter was marketed and sold by the Remington Arms Company in 1873. Years of refinement and use in the business world followed this initial product launch before typewriters were introduced to schools in the 1920’s. Soon thereafter, Ben Wood and Frank Freeman (1932) conducted a large-scale experiment to develop an understanding of how typewriters might be used in early elementary classrooms.

Occurring between 1929 through 1931, Wood and Freeman’s experiment was similar to many studies of computers conducted during the late 1980s and the 1990s in that the stated purpose of Wood and Freeman’s investigation was “to study the nature and extent of the educational influences of the portable typewriter when used as a part of the regular classroom equipment in the kindergarten and elementary school grades” (p. 1). In other words, rather than focusing narrowly on how the use of typewriters affected the writing skills of young children, Wood and Freeman were primarily interested in how instructional practices and classroom ecology changed. For this reason Wood and Freeman’s study examined how the typewriter could be integrated into the curriculum and the impacts that it had on teaching and learning.

Almost 15,000 students from eight public school districts and five private schools participated in the experiment. Treatment and control groups were formed in order to study the differences in student learning. Data that was analyzed included achievement test gains, student writing samples, teacher questionnaires, classroom observations, and student letters about why they like typewriting.

Based upon their study, Wood and Freeman (1932) concluded that there were three important reasons for using the typewriter in schools:

(1) to teach students skills that they will use later in life for personal or professional reasons

(2) to enable students to better learn English, spelling, arithmetic, geography, history, etc.,

(3) to develop those attitudes and habits which constitute so important a part of the aims of elementary school education” (p. 179).

Even though Wood and Freeman (1932) found evidence that typewriters could be used in early elementary classrooms, and this use had a positive impact on student learning, their recommendation to place typewriters in all early elementary classrooms was never implemented. In part, the high cost required for such large numbers of typewriters was not feasible, particularly when the nation was struggling with a major economic depression. Instead of being directly placed and used in classrooms as a writing tool, typewriters were used to prepare students for the business world by teaching high school students the professional skill of typewriting.

TELEVISION

Although it wasn’t until the 1950s and 1960s that instructional television reached its peak, the first documented use of closed circuit television was in Los Angeles public schools and at the State University of Iowa in 1939. While the popularity of instructional television was rising between 1939 and the 1950s, the overall United States educational system was facing harsh criticism.

Alleged evidence of the ailing educational system culminated with Russia’s launch of Sputnik in 1957. Fear that the Russians had surpassed the United States in science and technology led to educational reform efforts. Instructional television was viewed as one way to gain ground in the fight to stay ahead in technology. In response, financial support for instructional television poured in from many government and industry sources. The Ford Foundation alone “expended more than $300 million for the national educational television movement” (Saettler, 1990, p. 372).

Funding was provided for several types of instructional television application similar to the introduction of film. Some administrators and government officials hypothesized that television could provide students with a better education at a lower cost. To this end, a few school systems, such as Hagerstown Maryland and American Samoa, attempted to substitute a large portion of teacher-led classroom time with educational television programming. The primary reason for the infusion of television in these communities was the lack of certified teachers. In most schools, however, instructional television served a supplemental role and was used minimally. Cuban estimates that by 1975 primary-grade students spent on average only five hours a week learning through instructional television (Cuban, 1986. p. 32).

During the 1960s the television industry underwent a major transformation. In 1965, a Carnegie Corporation Commission recommended that “the federal government establish an independent, nonprofit Corporation for Public Television that would receive money from the government and other sources and distribute these funds to individual stations and independent production centers” (Saettler, 1990, p. 377).

Essentially putting into effect the Carnegie Corporation recommendation the Public Broadcasting Act was passed in 1967. Two years later, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) was established and in 1970 the Public Broadcasting Service was created to act as a distribution point and to manage the interconnection between stations.

All of these events in the public television industry would appear to set the stage for tremendous success of instructional television. However, some critics believe the end result hurt instructional television more than it helped. For example, Bronson criticized the way that the CPB handled instructional television, stating that it “indicates a questionable bureaucratic concern with directing social change rather than in promoting the development of educational broad casting” (Saettler. 1990, p. 384).

Although several early studies showed benefits of television over teacher instruction, later reports revealed that support for instructional television had diminished significantly. One source of this lack of support was from teachers. Typically, implementations of instructional television did not considered teacher needs or views. Cuban (1986) describes how, rather than consulting teachers, “television was hurled at teachers” (p. 36).

Interest in educational applications of televisions was revived in 1989 when a private, for-profit company began marketing an educational channel directly to schools. As Saettler (1990) describes, “Whittle Communications assembled a board of twelve educators and public figures to provide advice and direction for Channel One, a satellite-received news programming venture aimed at elementary schools” (p. 533). As an incentive to broadcast Channel One to students, Whittle Communications offered schools up to $50,000 of free televisions and video equipment and 1,000 hours of educational programming in exchange for a guarantee that students would watch 12 minutes of daily news programs which includes two minutes of paid commercials each day. Channel One has since changed its focus from elementary schools to middle and high schools, but maintains the same business plan.

Despite the fact that California and New York banned Channel One, by 1993 more than 8 million students nationwide watched Channel One’s programming daily (Barry, 1994, p. 103). Channel One, however, has faced strong opposition. As Saettler (1990) states, “All critics agree that the classroom should not become another market to exploit” (p. 534). Channel One is yet another example of the tension, and perhaps incompatibility between corporate America and the educational system.

TEACHING MACHINES AND PROGRAMMED INSTRUCTION

In the 1960s, behavioral psychology contributed to the educational technology field by introducing “teaching machines.” Reminiscent of Tiu! Turk, an 18th century “computer” that wore a turban and played chess (Standage, 2002), teaching machines were intended to teach students through thoughtfully programmed instruction.

The premise behind teaching machines was that objectives must be defined in advance and the extent to which these objectives are achieved must be measured. Students operated the machines themselves and followed instructions on a screen similar to a television. Typically, individual student cubicles were set up to block the noise made by the machines. This format minimized the amount of interaction among students and between students and the teacher.![]()

![]()

Books accompanied the teaching machines and functioned in an adaptive fashion, so that if a student did not understand a concept, the student is directed to a section that further explained it. If the student exhibited mastery of the concept, he or she was directed to the next topic. Teachers were able to program the teaching machines based on their desired curricular goals while students worked at their own pace through the lesson plans. But once programmed, it was the machine that directed students to the appropriate lesson, either in books or on the machine.

When using programmed instruction, students were first presented with material in successively more difficulty steps. The student was then asked to answer a question about the material. Some questions were multiple choice, while others used a fill in the blank format. The program then compared the student’s answer with the correct answer. Positive reinforcement was given to students who responded correctly while the proper response was provided to students who answered incorrectly. Skinner believed that all students should be administered the same set of questions, and students should be able to answer 95% of the questions correctly.

Later in the life cycle of teaching machines and programmed instruction branching algorithms and adaptive tests were developed to tailor the material and questions to an individual student’s needs. In general, evaluation of programmed instruction in the classroom showed that although implementation was difficult, the combination of teacher instruction and programmed instruction was more effective than either method used in isolation.

Skinner described the key characteristic of teaching machines and programmed instruction as “the arrangement of materials so that the student could make correct responses and receive reinforcement when correct responses were made” (Saettler, 1990, p. 294). This statement points to one of the major sources of conflict in the use of teaching machines. Too often teachers and administrators found themselves caught up in the excitement of using technology and neglected what many people now recognize as the more important component- the program of instruction. Students were sometimes bored with the level of instruction, and other times, they found ways to cheat the system and bypass lessons (p. 303).

Skinner introduced programmed instruction at Harvard University in 1957. A year later, Evans used the programmed instruction concept in books at the University of Pennsylvania. The first use of programmed instruction in an elementary school was in 1957 at the Mystic School in Winchester, Massachusetts. In general, though, teaching machines and programmed instruction were not widely used in public school classrooms or in higher education.

The popularity of teaching machines and programmed instruction followed the familiar cycle of most other forms of educational technology. In the late 1950s many people in the educational technology community expressed praise for this new tool: “In its short history this area of teaching technology has had a remarkably widespread effect on all forms of teaching” (Kay, Dodd, & Sime, 1968, p. 1). However, teaching machines and instructional programming never reached the stage of widespread use and in the late 1960s even the strongest proponents were backing down from their initial claims. Skinner once said, “… unfortunately, much of the technology has lost contact with its basic science. Teaching machines are widely misunderstood.” (Saettler, 1990, p. 303)

COMPUTERS

The research in the 1950s and 1960s on programmed instruction laid the foundation for the development of more advanced learning systems. Computers were first used in education in the 1960s in a way that was intended to individualize instruction. This method became known as computer assisted instruction (CAI).

CAI was intended to teach students a specific content area. Initially, the only difference between CAI and teaching machines was the type of technology used to deliver the material. Drill and practice techniques were common. “The student was asked to make simple responses, fill in the blanks, choose among a restricted set of alternatives, or supply a missing word or phrase. If the response was wrong, the machine would assume control, flash the word ‘wrong’ and generate another problem. If the response was correct, additional material would be presented.” (Saettler, 1990, p. 307)

The first generation of CAI programs used mainframe computers, was very expensive, and did not achieve the expected benefits of improving education through computer-based individualized instruction. However, this initial introduction of computers in schools spawned interest in a variety of other computer-based applications.

In the late 1970s the cost and availability of microcomputers reached a level at which it was more practical to place computers in K-12 schools. For a variety of reasons, parents, industry leaders, and government officials put pressure on school districts and principals to introduce computers into the schools. One reason for this computer enthusiasm was the fear that the United States was continuing to fall behind other world powers in terms of technology (C. Hunter, 1998), and teaching students to learn how to use computers seemed like one solution to this problem.

Another reason for the external pressure to use computers in schools was the perceived need to teach children job-related skills. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the importance of computers in the business world increased rapidly. As a result, teaching students how to use computers provided them with real-world skills and helped them become more competitive e in the job market.

Finally, it was argued that computers would make the educational process more efficient. Many computer advocates argued that a more refined version of the mainframe computer-assisted instruction would allow larger class sizes and, therefore, there would be a need for fewer teachers, since students would be able to rely on the computer for a significant portion of their learning.

Depending upon one’s perspective, the use of computers in schools differed significantly. For example, if the goal was to teach students how to use a computer so that they could obtain work skills, schools would introduce computer literacy classes into the curriculum. If the goal was to improve instructional efficiency, the computer was used as a tool to teach students the predetermined content. Finally, some people argued that the main benefit of using a computer in the classroom was to improve students’ problem-solving skills. This debate over how computers should be used in schools still exists today and is strikingly similar to the differences between Wood and Freeman’s rational for placing typewriters in elementary classrooms in the late 1920s versus the use of typewriters in business classes to teach discrete typewriting skills in order to prepare students for the workplace.

But no matter what the intended uses were, computers entered schools in large numbers during the early 1980s. Cuban (1986) references a survey that found an increase of 100,000 computers in schools over the year and a half between fall 1980 and spring 1982. Between 1982 and 1984, that number grew to 325,000 computers. By 1988, there were an estimated 3 million computers in schools (Saettler, 1990, p. 457).

Much of this growth can be attributed to corporate donations, which companies made in an effort to gain an edge in the educational computing market. Throughout the 1980s, IBM, Apple Computer, Hewlett-Packard, and Tandy all donated substantial numbers of computers to public schools. In elementary schools, these computers were generally used for repetitive drilling of specific content. In high schools, computers were generally used to teach students computer skills.

By the end of the 1980s, computers came under heavy scrutiny. Government leaders, parents, and school administrators wanted evidence of the effectiveness of using computers in schools. Instead of detailing benefits, researchers revealed a list of obstacles to the use of computers in classrooms. Similar to the problems identified with film, teachers felt that they were generally excluded from the development of instructional software and that the commercially available software generally did not meet their needs. Specifically, teachers felt that many of the available software packages did not engage students, and teachers felt that the drill and practice format was not an effective use of students’ time. Again similar to film, teachers also did not have the time or expertise to develop their own computer-based instructional materials. Finally, technical problems further frustrated teachers. All of these problems contributed to low usage. Saettler estimates that, on average, in the late 1980s, a typical student used a computer for less than 30 minutes a week.

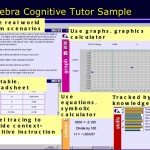

In contrast to the 1980s, the 1990s was a decade of new ideas and innovations for computer use in classrooms. With the introduction of color monitors and graphical user interfaces, more interactive and interesting content-based software packages were developed by companies like Tom Snyder Productions. In addition, simulations, intelligent tutors and cognitive-based learning tools such as DIAGNOSER (Minstrell, Stimpson, & Hunt, 1992) or the Algebra Cognitive Tutor (Anderson et al., 1995) began to show promise for improving classroom learning. Schools also began to understand the benefit of helping teachers determine how to integrate computers into their curriculum. While these advances did not correct all the obstacles to computer use identified by teachers during the late 1980s, they reignited interest in instructional uses of computers.

LEARNING MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS

Learning Management Systems (LMS), also known as Instructional Management Systems are online collaboration and communication tools which enable administrators, teachers and students to collaborate and communicate online in real-time across geographic distance. Some of the more popular commercial and open source LMS include Blackboard Learning System, Share-Point LMS, ANGEL Learning Management Suite, Sakai, and Moodle.

LMS combine online course management, communication and collaboration tools which can include a discussion forums, file exchange, email, online journal/blog, real-time chat, interactive whiteboards, bookmarks, calendar, search tool, group work, electronic portfolio, registration integration, hosted services, quizzes/surveys, marking tools/grade book, student tracking, content sharing and object repositories, amongst other tool offerings. (Fox, C., et al. (2009) pg. 8).

INTELLIGENT TUTORING

The field of cognitive science has exploded over the past decade and computer applications have emerged to take advantage of this new knowledge of how the brain works. Merging the fields of education and cognitive science has proven to be difficult. Bruer (1998) describes, “New results in neuroscience, rarely mentioned in education literature, point to the brain’s lifelong capacity to reshape itself in response to experience. The challenge for educators is to develop learning environments and practices that can exploit the brain’s lifelong plasticity,” (p. 9). One practical application of lessons learned from programmed instruction and new information about how the brain works came in the 1990’s in the form of intelligent tutoring.

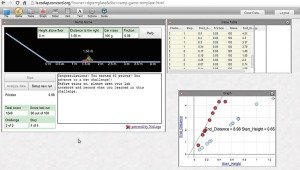

For the past decade, Carnegie Mellon has been developing cognitive tools. Carnegie Mellon’s first major tool, called the Practical Algebra Tutor (PAT), strives to improve students’ algebra skills and contains “a psychological model of the cognitive processes behind successful and near-successful student performance” (Koedinger, Anderson, Hadley & Mark, 1997, p. 32).

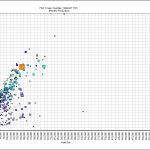

PAT is computer-based, uses real-world problems, and allows students to use several tools to solve a given problem. One example of a PAT problem is to determine which car rental company should be used on a vacation, given differing cost and terms of agreement information. Feedback is given to the student while he or she is solving the problem, allowing student misconceptions to be addressed while the student is still engaged with the problem. PAT uses model tracing to track a student’s progress throughout a problem and knowledge tracing to track a student’s progress in a series of problems. A Bayesian model, which estimates whether a student possesses a certain skill or knowledge of a particular subject, is used to highlight each student’s strengths and weaknesses. This information is then used to choose the next problem to be administered and to pace students.

The PAT program was first pilot tested in 1993 in three Pittsburgh high schools. Since then, the intelligent tutoring tools have been expanded to include a fully developed series of products (Algebra I, Geometry, Algebra II, Integrated Math Series and Quantitative Literacy) that are being used throughout the country. Through a series of studies conducted over the past decade (see Corbet, 2002 for a review of this research), evidence suggests that a diverse population of students “including mainstream, non-mainstream, gifted, minority, ESL and inclusive education students all benefit” from the use of the Cognitive Tutor® curricula (Carnegie Learning, 2002, para.

Similarly, researchers at the Concord Consortium have been working on an intelligent tutoring device that focuses on genetics and scientific reasoning skills. The system is intended to help eighth-, ninth-, and tenth-grade students learn about genetics through guided exploration. Most often, the system introduces students to new concepts by asking students to explore a specific topic through manipulation of genetic traits of a fictitious species of dragon. As students work with the system, new concepts are revealed through guided exploration. For example, the first set of explorations during one lesson culminates by asking students to describe how traits are produced in dragons.

At times, the learning system presents textual or graphical information to explain concepts and provides students with access to various tools and pieces of information via menu selections. In addition, the system often asks students to demonstrate their understanding through written responses to specific questions, multiple-choice questions and, most often, the modification of different aspects of genetic codes to create dragons with specific traits or to determine how a trait suddenly appears in a generation of dragons. From an instructional perspective, Biologica enables students to explore a complex topic via a variety of media and enables teachers to work individually or with small groups of students as questions arise.

Although these tools are being used in a relatively small number of classrooms, they show tremendous promise for using technology as a tool that assists students and teachers in both identifying and correcting misconceptions in a timely manner.

THE INTERNET

Today, the Internet is one of the more popular forms of educational technology used in classrooms. Although some college level courses can be taken online, often without any student-teacher interaction, this type of use is just beginning to penetrate K-12 public schools, particularly at the high school level. As an example, the Virtual High School (VHS) was launched in the late 1990s. Since then, VHS has grown and served approximately 3,000 students in more than 150 schools with 134 online courses in 2001. Similarly, the Florida Virtual School provides free, online instruction to 6,900 students enrolled in 65 Florida county school systems.

In addition to online courses, there are a variety of ways that the Internet is being used in classrooms. A 2002 study by the American Institutes for Research found that students use the Internet for school in the following five ways:

as a virtual textbook and reference library

- as a virtual tutor and study shortcut

- as a virtual study group

- as a virtual guidance counselor

- as a virtual locker/backpack and notebook

(Levin & Arafeh, 2002, p. iii). Teachers also integrate Internet-based activities into their lessons. In some cases, teachers will use data or simulations available on the Internet to demonstrate a concept or work through a problem with the whole class. With the rapid increase in Applets (mini-applications that are available on the Internet), teachers have access to powerful tools that enable easy manipulation of data and displays information in a manner that often makes it easier for students to visualize concepts.

As one example, the Technology and Assessment Study Collaborative has developed a set of applets that focus on specific statistical concepts (www.bc.edu/research/intasc/tools.shtrnl). These tools enable teachers and students to generate scatterplots that meet specific conditions (e.g., a correlation between two variables of .65 with 200 cases). The correlation applet also allows the user to move individual data points around within the scatterplot and then see how this change in a single data point affects the correlation. In addition, the applet allows the user to manipulate a “line of best fit” by clicking and dragging it on the screen. As the line is moved, the error of prediction is updated automatically enabling the user to visually explore how changes in the line affect the accuracy of the prediction. Applets developed by other organizations allow teachers to model scientific principles such as plate tectonics and sound waves by manipulating data and then visually displaying the effects.

Teachers also direct students to use the Internet to find and explore information related to a specific topic of study. As an example, many upper elementary and middle school teachers have students perform web-quests. In some cases, web-quests take the form of problems that require students to find and apply information to solve. As an example, a teacher might present a problem in which an animal that lives in Australia has decided to relocate to one of three areas within the United States. Students are then asked to use the Internet to find specific information about the animal and about each area of the United States and to then use this information to write a recommendation to the animal that includes data to support the recommendation. In other cases, web-quests take a more mundane form in which students are given a list of actual questions and are asked to use the Internet to find the answers.

While there are many more examples of computer-based tools that are used in today’s classrooms, there is no question that computers are the most recent technology that has penetrated the American educational system. However, an important question that remains largely unanswered focuses on how computer use in schools is affecting teaching and learning.

THE CLOUD

Although technically part of the internet, because of its impact on K-12 education cloud technology should be looked at separately.

Cloud computing relies on sharing of resources to achieve coherence and economies of scale, similar to a utility (like the electricity grid) over a network. At the foundation of cloud computing is the broader concept of converged infrastructure and shared services. Cloud resources are usually not only shared by multiple users but are also dynamically reallocated per demand. This approach maximizes the use of computing power thus reducing environmental damage as well since less power, air conditioning, rack space, etc. are required for a variety of functions. With cloud computing, multiple users can access a single server to retrieve and update their data without purchasing licenses for different applications.

The present availability of high-capacity networks, low-cost computers and storage devices as well as the widespread adoption of hardware virtualization, service-oriented architecture and autonomic and utility computing have led to a growth in cloud computing. School districts can scale up as computing needs increase and then scale down again as demands decrease. (Wikipedia)

Different schools use different devices at different grade levels which mean varying data storage needs. And, for example, there is no need to shoehorn an infrastructure built for the Android operating system to fit a Mac-only school. Using “standards-based vendor control” cloud technology allows the accommodation of the districts for any device choice, whether it is a Chromebook, an Android device, or an Apple device which typically have no hard drives. The cloud technology allows the schools to pick the device and to find the common denominators in delivering support services.

Freedom of choice applies to where students can do their work. A lot of local school districts rely on local outreach programs from their city, from local businesses where students might have remote labs. They might have libraries or boys and girls clubs where they need access to their information on a device that they might be able to have for an hour or two at a time. Cloud technology allows the entire curriculum and supplements to be connected to the student’s online identity and account—and not to a specific device.

Cloud technology allows secure access for students, teachers, and administrators to enter cloud storage from any device at any time, via a Dropbox-style entry point. And the cloud is large enough to accommodate an “archive forever” infrastructure. This means that teachers retain access to curriculum and student data, while students can always access projects that might be part of an e-portfolio. (http://thejournal.com/Articles/2013/06/05/Sharing-the-Cloud-in-Illinois.aspx?Page=1)

CONCLUSION

It’s fascinating to review how western education technology has evolved. Just as our culture and society have become more complex formal education has become more multifaceted to keep pace. So what’s next? Who knows but with as fast as technology is advancing we probably have not seen anything yet. Maybe devices like Google Glass, where students wear a computer as eyewear or maybe a planetarium like classroom where all manners of education will simply swirl around the students heads.

But what’s more important than any new device, or even the existing one, is to track how effect these devises are in aiding student gain the knowledge and skills they need for today’s world. All these classroom devices are neutral what’s not neutral is determining just what is the knowledge of most worth in a contemporary society. Of course we have been arguing about that forever but not only does the curriculum have to relevant it also has to be interesting for the student. Once that’s determined all these devices will be standing by to make learning multi-dimensional and brought to life in the classroom.

References

Russell, M. (2006) Technology and Assessment: The Tale of Two Interpretations, Information Age Publishing (pp. 137-152)

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2010/09/19/magazine/classroom-technology.html?_r=0

![PhilTV50[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/PhilTV501-150x150.jpg)

Recent Comments