K-12 Teacher Evaluation

NCLB TEACHING STANDARD

Prior to the No Child Left Behind Act, new teachers were typically required to have a bachelor’s degree, to be fully certified, and to demonstrate subject matter knowledge, generally through tests. Under NCLB, existing teachings including those with tenure were also supposed to meet standards. They could meet the same requirements that were set for new teachers or could meet a state-determined “High Objective Uniform State Standard of Evaluation,” (HOUSSE). Downfall to the quality requirements of the NCLB legislation have received little research attention, in part because state rules require few changes from pre-existing practice. There is also little evidence that the rules have altered the trend lines in the observable traits of teachers.

Under NCLB, existing teachings including those with tenure were also supposed to meet standards. They could meet the same requirements that were set for new teachers or could meet a state-determined “High Objective Uniform State Standard of Evaluation,” (HOUSSE). Downfall to the quality requirements of the NCLB legislation have received little research attention, in part because state rules require few changes from pre-existing practice. There is also little evidence that the rules have altered the trend lines in the observable traits of teachers.

EXAMS FOR TEACHERS

In 2011, the Obama administration agreed to issue a two-year waiver of the No Child Left Behind law for states that meet three main criteria: adoption of rigorous academic achievement standards, a program to focus on turning around low performing schools, and the most contentious provision, an accountability system that would involve using test scores to evaluate teachers and principals.

In 2011, the Obama administration agreed to issue a two-year waiver of the No Child Left Behind law for states that meet three main criteria: adoption of rigorous academic achievement standards, a program to focus on turning around low performing schools, and the most contentious provision, an accountability system that would involve using test scores to evaluate teachers and principals.

The American Federation of Teachers wants a serious professional exam for K-12 teachers similar to a bar exam for lawyers and a board certification for doctors. A panel of education experts and teachers has been developing ways to improve teacher performance.

Prospective teachers who have educational school training would have to, “demonstrate knowledge of their subject areas; understand the social and emotional elements of learning; and spend a year in ‘clinical practices’ as a student teacher before passing a comprehensive exam.” Another feature of the plan would require a 3.0 grade average for university selection to a teacher preparation program.

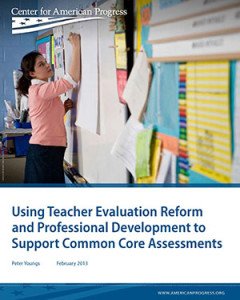

COMMON CORE AND TEACHER EVALUATIONS

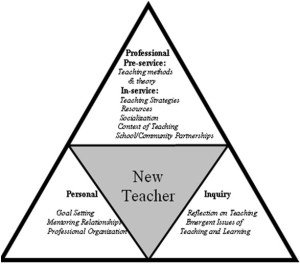

With the advent of the Common Core Standards more than 30 states are implementing new systems to evaluate teachers using more rigorous criteria about what makes a good teacher. Many of the states are designing their evaluation criteria based The Danielson Group’s system of evaluation. Charlotte Danielson specializes in designing system to evaluate teacher effectiveness that also promotes teacher professional learning.

states are designing their evaluation criteria based The Danielson Group’s system of evaluation. Charlotte Danielson specializes in designing system to evaluate teacher effectiveness that also promotes teacher professional learning.

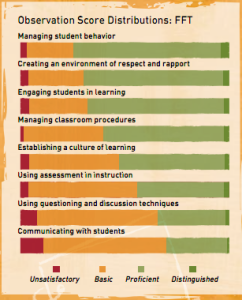

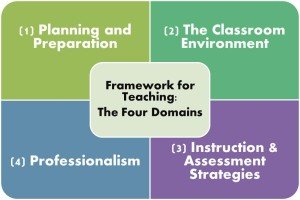

Danielson’s system, called the “Framework for Teaching,” includes 22 indicators to use when observing teachers in the classroom, each scored on a four-point rating scale. The indicators include skills as varied as “creating an environment of respect and rapport” and “demonstrating knowledge of content and pedagogy” to “communicating with families” and “maintaining accurate records.”

THE FRAMEWORK FOR TEACHING

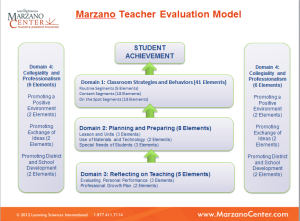

The Framework for Teaching is a research-based set of components of instruction, aligned to the Interstate Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium (INTASC) standards, based on a constructivist view of learning and teaching. The complex activity of teaching is divided into 22 components (and 76 smaller elements) clustered into four domains of teaching responsibility:

Each component defines a distinct aspect of a domain; two to five elements describe a specific feature of a component. Levels of teaching performance (rubrics) describe each component and provide a roadmap for improvement of teaching.

The Framework may be used for many purposes, but its basic value is in providing a foundation for professional conversations among practitioners as they enhance their skill in the complex task of teaching. The Framework may be used as the foundation of a school or district’s mentoring, coaching, professional development, and teacher evaluation processes.

Training for all teachers, school leaders, and staff using the Framework is recommend. Developing a common understanding is important for accuracy, teaching advancement, and the Framework’s impact on students’ core learning.

Domain 1:

Planning and Preparation

1a Demonstrating Knowledge of Content and Pedagogy

1b Demonstrating Knowledge of Students

1c Setting Instructional Outcomes

1d Demonstrating Knowledge of Resources

1e Designing Coherent Instruction

1f Designing Student Assessments

Classroom Environment

2a Creating an Environment of Respect and Rapport

2b Establishing a Culture for Learning

2c Managing Classroom Procedures

2d Managing Student Behavior

2e Organizing Physical Space

Domain 3:

Instruction

3a Communicating With Students

3b Using Questioning and Discussion Techniques

3c Engaging Students in Learning

3d Using Assessment in Instruction

3e Demonstrating Flexibility and Responsiveness

Domain 4:

Professional Responsibilities

4a Reflecting on Teaching

4b Maintaining Accurate Records

4c Communicating with Families

4d Participating in a Professional Community

4e Growing and Developing Professionally

4f Showing Professionalism

According to a recent Hechinger Report “No Consensus on which Skills should be Included in Teacher Evaluations,” as part of Common Core new systems to evaluate teachers are now being implemented at the state level. The criterion to accomplish this is supposed to be more rigorous but the problem is, unlike the new Common Core Standards there is little agreement on what that criteria should be.

The question is can the quality of a teacher be measured by looking at just a few key skills, such as setting academic goals and running an effective class discussion? Or should teachers be evaluated based on a broader range of abilities, including lesson-planning and content knowledge? Teacher evaluations have become highly controversial as states introduce increasingly different models.

In Los Angeles, teachers will soon be evaluated on a list of 61 criteria during classroom observations conducted by school administrators. Louisiana, by contrast, requires principals to look at just five skills in the observation portion of the state’s new teacher evaluations. In most classrooms in Tennessee, principals use a checklist that includes 19 skills during observations that are part of a new, more intensive evaluation system launched last year. In each place, a teacher’s rating will be based on a combination of classroom observations and student achievement data.

Both the longer and shorter observation checklists have met with criticism. The Los Angeles Times reports that while teachers participating in the roll-out of a new evaluation system planned for th e Los Angeles Unified School District are generally optimistic about it, many administrators are concerned about the time it takes to observe and rate teachers on 61 skills. It is felt by some that Louisiana’s fewer criteria is too simplistic and may lead to lawsuits.

e Los Angeles Unified School District are generally optimistic about it, many administrators are concerned about the time it takes to observe and rate teachers on 61 skills. It is felt by some that Louisiana’s fewer criteria is too simplistic and may lead to lawsuits.

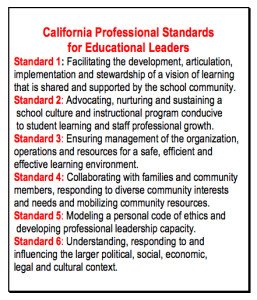

The Los Angeles district added extra skills to some of the evaluation areas to reflect California standards for teachers. And although the framework in Los Angeles is lengthy, the district is only focusing on a handful of areas including “classroom climate” and “teacher interaction with students.”

These two indicators appear in other school districts across the country, but the importance they are given in different rating systems varies. Florida’s Miami-Dade school district has also made teacher-student relationships a priority. There, teachers are rated on eight performance standards including “learning environment,” which holds more weight in the evaluation score than the standards evaluating professionalism and communication. In Louisiana, assessments and procedures, or the extent to which the class “runs itself” through routines, are the priority, and separate indicators measuring a classroom’s climate and learning culture were dropped.

Despite the lack of agreement about the details, the evaluations are becoming increasingly important as more states are using new evaluations to determine who can stay in the classroom. Under Louisiana’s new system, teachers could lose their certification if they receive an “ineffective” rating for two years in a row. In Washington, D.C., 7 percent of the teaching force was fired after a controversial new evaluation system was launched two years ago. (The District of Columbia Public Schools originally included a total of 22 standards in its observation framework but dropped the number to 18 after teachers complained that the number of requirements was overwhelming.)

When the “Measures of Effective Teaching” project, a study in six districts funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, observed nearly 3,000 teachers using five different observation systems, researchers found that it didn’t really matter which practices were emphasized on an evaluation. Teachers who more effectively demonstrated the types of practices emphasized in any given system had greater student achievement gains than other teachers.

But educators and researchers say the observation process is not meant just to identify which teachers are high- evaluation should be to develop expert teachers who are self-correcting,” said Michael Toth, CEO of the Learning Sciences Marzano Center for Teacher and Leadership Evaluation, an organization that develops teacher evaluation tools, in a press release. Toth cited results of a study that found teachers assessed with more detailed observation tools are more likely to change their classroom practices. “The more specific the model is … the better the model will be in driving teacher development,” Toth said.

But educators and researchers say the observation process is not meant just to identify which teachers are high- evaluation should be to develop expert teachers who are self-correcting,” said Michael Toth, CEO of the Learning Sciences Marzano Center for Teacher and Leadership Evaluation, an organization that develops teacher evaluation tools, in a press release. Toth cited results of a study that found teachers assessed with more detailed observation tools are more likely to change their classroom practices. “The more specific the model is … the better the model will be in driving teacher development,” Toth said.

Some teachers in Los Angeles told the Los Angeles Times that their new evaluation system does just that by focusing on specific areas and encouraging collaboration and reflection. Last year, 450 teachers and 320 administrators tested the system. By the end of this school year, every principal and one volunteer teacher at each school in the district will be trained, with a district-wide roll-out date still to be determined.

(The following is an abstract of Ashly McGlone’s article, “As state watches, LA Unified tests new ways to grade teachers,” Center for Investigative Reporting 6/3/2013)

Nowhere else in California has the debate over the use of student test scores to grade teachers gained more attention than in the Los Angeles Unified School District. The second-largest school district in the nation at more than 640,000 students, Los Angeles Unified has become a testing ground to increase accountability for teachers, a movement that has gained speed across the nation.

The district – propelled by a lawsuit and led by Superintendent John Deasy, a darling of reformers who support the effort to overhaul teacher evaluations – has pushed to use mathematical algorithms known as value-added measurement to provide what proponents say is more precise quantitative information about a teacher’s performance. The local union, United Teachers Los Angeles, has fought back furiously and argued against any cookie-cutter approaches.

A deal ratified earlier this year allows the district to use state test scores and the Academic Growth Over Time measurement, which includes past test scores and demographics like family income, language and ethnicity. The deal specifically prohibits the use of individual teacher growth scores other than to “give perspective and to assist in reviewing the past CST (California Standards Test) results of the teacher.”

Critically, however, the agreement is silent on how much weight student data has. An announcement by Deasy in February that student data could account for up to 30 percent of a teacher’s evaluation was met with mixed responses.

“I don’t understand why anybody would be upset with 30 percent of your evaluation being tied to student achievement; that means 70 percent is not,” she said Robin Wynne Davis a third-grade teacher at Melrose Elementary School. “We are teachers, for God’s sake. I mean, how are you supposed to be judged if you are not using the kids’ work?”

Although the use of test scores remains the most controversial piece of the evaluations, it remains to be seen how the main portion of the evaluations, which are based on intensive, time-consuming qualitative measures of a teacher’s performance, will affect schools and classrooms.

Although the use of test scores remains the most controversial piece of the evaluations, it remains to be seen how the main portion of the evaluations, which are based on intensive, time-consuming qualitative measures of a teacher’s performance, will affect schools and classrooms.

In the pilot, state test score gains in a particular class were analyzed and scored relative to the student’s predicted growth based on past scores, and relative to the average gains seen across the district and within different groups of the student population. But the main focus of the pilot was to test the new qualitative measures.

Lengthy and more detailed evaluation score sheets are given to teachers for self-assessment and principals for observations. What was once a four-page evaluation is now 26 pages with descriptions of what an “ineffective,” “developing,” “effective” and “highly effective” teacher looks like in 61 areas; based on participant feedback, the district limited reviews to 21 areas this year.

Principals also are required to write exactly what they see and hear in the classroom as evidence and rationale of the teacher’s evaluation, a requirement that can leave observers tied to their computers and unable to take in the entire class experience, several pilot participants said. Because principals are working with one teacher as a part of the pilot, it’s unclear what the burden will be when they have to observe all of their teachers when the new system rolls out.

The pilot also tried to address the tricky issue of how to provide student achievement measures for the vast majority of teachers of grades and subjects that are not tested on a state exam, including physical education and art. For now, those teachers, particularly in the early grades, must cobble together a variety of measurements to give some sense of their performance

EXAMINING STUDENT TEST SCORES

Nationally, experts have disputed whether student test score data can be used reliably to measure teacher performance – but nearly all agree that such data should be coupled with more qualitative information to ensure fairness and make sure the evaluations are useful to teachers.

Proponents say the test data is appropriate because it’s one way to measure what’s supposed to be the ultimate outcome of teaching – whether students are learning. The data also can provide a counterweight to principals’ observations, which, depending on how they’re structured, also can have reliability problems. The piloted changes focus on evaluation as “a growth and development tool rather than a punitive tool,” which will tie results to “aligned, targeted, professional development opportunities for teachers.”

Proponents say the test data is appropriate because it’s one way to measure what’s supposed to be the ultimate outcome of teaching – whether students are learning. The data also can provide a counterweight to principals’ observations, which, depending on how they’re structured, also can have reliability problems. The piloted changes focus on evaluation as “a growth and development tool rather than a punitive tool,” which will tie results to “aligned, targeted, professional development opportunities for teachers.”

States and districts mostly have opted to look at student growth, as opposed to raw test scores, because raw scores can disadvantage teachers with large numbers of low-income, limited-English or special needs students, who tend to score lower on standardized tests.

Critics of growth measures have said they can fluctuate depending on the variables and number of years of testing data added to the mathematical formula, making their validity suspect, and worry that grading teachers based on tests will cause them to focus more on test prep in their classrooms.

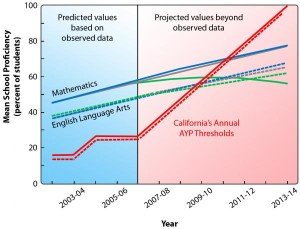

There’s another reason for the district to be motivated. Los Angeles Unified hopes to opt out of federal student accountability sanctions coming its way in 2014 under the No Child Left Behind Act. The Obama administration offered waivers from the law’s requirement that states steadily increase the number of students graded proficient on standardized exams to 37 states that agreed to other accountability measures, including new evaluations for teachers and principals.

With the promise of local accountability and coordinated efforts to improve, the district is one of nine in a consortium called the California Office to Reform Education – which includes Oakland, Sacramento and San Francisco – seeking a waiver from the U.S. Department of Education. If approved, it would be the first district-level waiver obtained in the offer intended for states.

Other districts and states also have responded to the Obama administration’s urging – through No Child Left Behind waivers and grant competitions like Race to the Top – that districts and states overhaul their evaluations.

Other districts and states also have responded to the Obama administration’s urging – through No Child Left Behind waivers and grant competitions like Race to the Top – that districts and states overhaul their evaluations.

According to a review by the National Council on Teacher Quality, a Washington, D.C.-based reform group, 20 states in 2012 required student achievement as a significant part of judging teacher performance, including multiple states where student data accounts for 50 percent of an evaluation. In 2009, four states required student data in a significant way. In many of those places, policymakers have encountered similar resistance from unions and educators on the front lines.

Teacher Denise Casco at Vista del Valle Dual Language Academy in San Fernando said the inclusion of student achievement could disproportionately affect her because she serves a more disadvantaged community than others in the district. She said she worries her students are more likely to lag behind on tests. Nearly all 500 students on campus in the far northern part of the district are socioeconomically disadvantaged, and half are English-language learners.

“The playing field is not even,” said Casco, who is in her ninth year of teaching. “The funding is not even; the level of support is not even. So I am very cautious at putting a number or percentage for a particular level of student achievement in a teacher evaluation process.”

But not all of the changes are concerning, she said. Like many teachers around the country, she has embraced the more intensive classroom observations, which tend to offer teachers more specific feedback than previous versions. As a kindergarten teacher last year who participated in the pilot program, Casco had a videotaped math lesson that was selected by the district as a model to train administrators on what to look for during an observation.

In it, her 5- and 6-year-old students are working in small groups. Students play a series of games related to frogs and fish to practice adding and subtracting and eventually are asked to illustrate a story with an equation and grade their own performance on a rubric.

“It forces you to reflect,” Casco said of the evaluation changes, which include the principal asking teachers after the observation if they achieved their objective. “It did hold me more accountable to the results than the old evaluation system would have.”

LAWSUIT SEEKS TO STRIKE SOME TEACHER PROTECTIONS

The spotlight on teacher evaluations widened last June when Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge James Chalfant ruled that the district was violating California’s longstanding teacher evaluation law, the Stull Act, by not ensuring test scores were used.

The 1971 law, signed by then-Gov. Ronald Reagan and named after a former Republican lawmaker, requires student achievement to be included in teacher evaluations – something Los Angeles Unified, and most districts, resisted for decades. Some districts found they didn’t need to fully comply with the Stull Act to receive millions of dollars from the state designated for linking teacher evaluations to student achievement.

Student plaintiffs filed a lawsuit last May against the state of California and several local districts, including Los Angeles Unified. The lawsuit aims to increase the impact of teacher evaluations by striking down multiple protections teachers have under the law.

Represented by Los Angeles law firm Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP, the plaintiffs allege teacher protections such as tenure, seniority rules in layoffs and other teacher dismissal statutes disparately keep ineffective teachers in the classroom in violation of the state constitution’s equal protection clause. The case also cites court opinions that have held that “the right to an education today means more than access to a classroom” and that the state “has broad responsibility to ensure basic educational equality.”

Represented by Los Angeles law firm Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP, the plaintiffs allege teacher protections such as tenure, seniority rules in layoffs and other teacher dismissal statutes disparately keep ineffective teachers in the classroom in violation of the state constitution’s equal protection clause. The case also cites court opinions that have held that “the right to an education today means more than access to a classroom” and that the state “has broad responsibility to ensure basic educational equality.”

Deasy and Xavier De La Torre, Santa Clara County’s superintendent of schools, have endorsed the case, according to the nonprofit Students Matter, the advocacy group sponsoring the lawsuit. After failed efforts by the state to get the case dismissed in the last year, a judge granted a request by the California Teachers Association and the California Federation of Teachers to join the lawsuit as defendants May 2. A trial date is set for Jan. 27, 2014.

Los Angeles Unified parent Lauren Campbell has a child plaintiff in the case and said that even though efforts are underway to overhaul the evaluation system in the district, it won’t do much to protect effective, less-senior teachers who she says she has seen get layoff notices year after year at Lanai Road Elementary School in Encino.

“I think that if we value education and we say we want great teachers for our kids, we need to make that job attractive, and part of the way to do that is not fire the best ones every year,” Campbell said. Los Angeles Unified parent Lisa Liss also argues that the layoff system targets great teachers over less effective ones. “The impact of having a really bad teacher goes way beyond one academic year. Those kids end up behind for years to come and maybe even permanently,” she said, “so every child should have a great teacher.”

Liss said you have to go to the top to get the wide-reaching changes needed. “Individual changes will take forever,” she said. “To make a wholesale change at a much higher level is going to be much more effective and much quicker, and these kids don’t have much time to waste. Their education is happening now, not in 20 years.”

TEACHER EVALUATION CRITERIA

(Combination of classroom observations and student achievement data)

- Setting academic goals

- Running an effective class discussion

- Lesson-planning

- Content knowledge

- Classroom’s climate and learning culture

- Teacher interaction with students

- Teacher-student relationships

- Learning environment

- Professionalism and communication

- Assessments and procedures, or the extent to which the class “runs itself” through routines

Recent Comments