Textbook & Supplement Articles

K-12 Textbooks and Supplements

WHAT’S HAPPENING AT THE CORE? (Part II)

By Sarah Bayliss

School Library Journal2/2014

(For Part I of his article see: Common Core Initiative/articles)

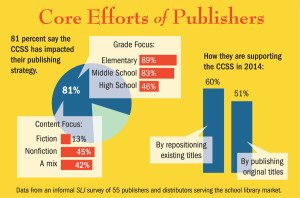

Publishers and distributors are providing a flood of CCSS-aligned materials and professional development (PD) support, ranging from teacher manuals and conferences to webinars to interactive learning tools. According to an informal December 2013 SLJ survey of 55 publishers and distributors who serve the school library market, 81 percent provide texts aligned to the CCSS, particularly for grades K–5 and 68 percent offer PD materials. Sixty percent will reposition existing titles to show CCSS alignment this year, and 51 percent will develop original titles for the same purpose.

Educational publishers are seeing their highest profits in eight years. Revenues rose by seven percent through September 2013, compared to a 14 percent decline in 2012, says Jay Diskey, executive director of the PreK–12 Learning Group Division of the Association of American Publishers. Such an increase has not occurred since 2005, Diskey says, though “the Common Core is not the only reason for that. This is a bounce-back from the recession. The educational publishing industry was hit very hard. School districts were broke.” He adds, “We have seen a pent-up need for new materials.”

Quest for Resources

Teachers want support; publishers are providing lots of it. Some maintain that educators are struggling due to the lingering impact of the recession, publishers’ revenues notwithstanding. “Reform needs a lot of money behind it,” says Nell Duke, professor of literacy, language, and culture and a faculty associate in the combined program in education and psychology at the University of Michigan. “The Common Core has come at a moment when school budgets are really strained. It’s bad timing.  Budgets are shrinking, and adopting the Common Core doesn’t necessarily come with money.” Duke says, “The biggest [need is for] professional development.”

Budgets are shrinking, and adopting the Common Core doesn’t necessarily come with money.” Duke says, “The biggest [need is for] professional development.”

Publishers’ and distributors’ offerings include an explosion of CCSS-aligned titles—49 percent offer CCSS collections and series—plus educational technology, databases, and other materials, according to SLJ’s survey. Eighty-nine percent produce materials for K–5; 83 percent also focus on the middle grades; while 46 percent generate high-school level CCSS offerings. Regarding content, 45 percent focus on nonfiction, a major shift in the new standards; 13 percent on fiction; and 42 percent a mix of both.

Duke and others applaud the nonfiction emphasis. “I’ve been advocating for informational texts for young children for a long time,” she says. Wooten also likes the potential for biographical picture books in the new curriculum.

Within PD materials, 83 percent provide teacher guides, 63 percent reader guides, 40 percent offer digital discussion guides, and 30 percent have created PD resource lists, along with webinars, conferences, one-on-one support, regional and statewide coaching, and other resources.

Publishers and the Common Core

Everyone’s in on the action. To start, publishers large and small offer sites searchable by the standards to varying degrees of sophistication and support material, including the major trade publishers—Hachette, Penguin Random, HarperCollins, Macmillan, and Simon & Schuster—along with educational, series, and smaller niche publishers.

Everyone’s in on the action. To start, publishers large and small offer sites searchable by the standards to varying degrees of sophistication and support material, including the major trade publishers—Hachette, Penguin Random, HarperCollins, Macmillan, and Simon & Schuster—along with educational, series, and smaller niche publishers.

Common Core-positioned titles are a natural for primarily nonfiction publishers including Rosen, Lerner, Clarion, National Geographic, Rourke, and others. Lerner provides CCSS research and writing tools through its Common Core Connections site and Common Core Libraries series, along with detailed information on text complexity. ABDO’s imprint, Core Library, features more than 300 CCSS-related titles.

Common Core-positioned titles are a natural for primarily nonfiction publishers including Rosen, Lerner, Clarion, National Geographic, Rourke, and others. Lerner provides CCSS research and writing tools through its Common Core Connections site and Common Core Libraries series, along with detailed information on text complexity. ABDO’s imprint, Core Library, features more than 300 CCSS-related titles.

“We welcome the Common Core,” says Roger Rosen, president of Rosen Publishing. “We think it’s an elegant document and well-conceived, encouraged by the assumption of rigor for all students. A refusal to dumb down materials and have kids read and be engaged in a way we feel very congruent with.”

“We embrace the notion of 21st-century learning, not just as consumers of information but creators,” Rosen adds. That vision is embedded within the company’s publishing program—on the print side and on the digital. Products like Rosen Classroom’s InfoMax Common Core Readers, Rosen Interactive Ebooks, and Digital Literacy database support comparative text analysis and other standards.

The CCSS provides “a good opportunity to re-promote books that are being used in the classroom,” says Lucy Del Priore, Macmillan Children’s Publishing Group school and library marketing director. Del Priore says that titles by Macmillan authors from Jack Gantos to Peter Sís are being positioned for CCSS teaching. Other trade publishers are following suit. Dorling Kindersley, a division of Penguin Random, features deep Common Core offerings at us.dk.com/commoncore, while Penguin Young Readers also offers CCSS materials. Simon & Schuster’s Common Core site features CCSS teachable titles—such as Brian Floca’s Locomotive—with discussion questions, and many other resources.

The CCSS provides “a good opportunity to re-promote books that are being used in the classroom,” says Lucy Del Priore, Macmillan Children’s Publishing Group school and library marketing director. Del Priore says that titles by Macmillan authors from Jack Gantos to Peter Sís are being positioned for CCSS teaching. Other trade publishers are following suit. Dorling Kindersley, a division of Penguin Random, features deep Common Core offerings at us.dk.com/commoncore, while Penguin Young Readers also offers CCSS materials. Simon & Schuster’s Common Core site features CCSS teachable titles—such as Brian Floca’s Locomotive—with discussion questions, and many other resources.

While Macmillan’s digital catalog is “a terrifically filtered database,” Del Priore says, she believes that educators will go to the distributors, including Baker & Taylor, Ingram, Follett, and Mackin, in order to find their teaching resources.

To help educators navigate materials, “Common Core information is being filtered down by professors and people writing articles,” Del Priore adds. “Do you want to go to 10 websites for resources, or one spot?” She notes, “We share [our materials] with third-party sites like TeachingBooks.net. Teachers are more likely to go to a source like that.”

“We’re curating the materials that publishers are providing,” says Baker & Taylor director of merchandising Diane Magnan. “The strategy is around credibility and cutting through the noise out there.” This month, the distributor is launching a revamped site devoted to the CCSS with “publishers’ resource teaching guides, reading group guides, and lists based on appendixes,” among other resources. Educators tell Magnan, “Don’t just put a sticker on a book.” They’re looking for deeper guidance.

Mackin Educational Resources seeks to provide that through the distributor’s Classroom Services, featuring a CCSS focus, along with its Core Knowledge title lists and other resources, including those for PD. Follett’s support encompasses CCSS text exemplars, curriculum maps, and more.

For Solution Tree, a company dedicated to professional development, materials oriented to the CCSS now constitute about 10 percent of revenue, says Solution Tree Press president Douglas Rife. “Seven of our top 10 titles in 2013 were on the Common Core,” he says, with webinars, Web conferencing, coaching, interactive video, and support for English-Language Learners (ELL) in the mix. “We do a lot of custom work” on the state, district, and local level, Rife says. “The next big wave is going to be assessment” support materials.

In addition to the teaching titles, Capstone’s division Capstone Professional Services features “webinars supporting Capstone professional titles written by educators who are experts in their field and the Common Core,” according to Cox. Along with features such as CCSS resources in Capstone Classroom, “We have 100 Capstone reps across the country visiting libraries every day.”

In addition to the teaching titles, Capstone’s division Capstone Professional Services features “webinars supporting Capstone professional titles written by educators who are experts in their field and the Common Core,” according to Cox. Along with features such as CCSS resources in Capstone Classroom, “We have 100 Capstone reps across the country visiting libraries every day.”

Enslow Publishers takes a different approach to CCSS guidance. “We tried to solve the problem of Common Core correlations and anchor standards looking like a bunch of numbers and letters,” says president Mark Enslow. “We use a visual way of showing how our books fit the Common Core.” The sophisticated website uses “green checks where we show the anchor standards—scaled to national standards.”

Enslow adds, “I found that school librarians were pretty much on top of” the standards during conversations at the American Association of School Librarians conference. “But when our public library customers came by, they were quite confused. There’s work to be done there. They wear so many hats and serve so many clients.”

“Teachers tell me they want short, high-interest texts they can read in one class period,” says Rebecca Hinson of Rebecca Hinson Publishing, focusing largely on visual and art books.

Hinson’s offerings are often geared toward ELL students, who comprise 10 percent of the US public school population, and Hispanic students, who comprise 25 percent, according to Hinson.

Florida-based Hinson sees that teachers “just want their kids to pass” the assessments. Ninety-one percent of ELL students failed the reading portion of the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test, she says.

Last year was “the largest year ever within the educational unit of Scholastic,” says Margery Mayer, president of Scholastic Education, which offers text pairing, lesson plans, and PD in person in a variety of settings, and a range of other resources. Scholastic reps in the field will conduct “a workshop, classroom coaching, or give a presentation with a leading educator.” She adds that Scholastic supports “the half to two-thirds of students who are not reading proficient.”

Scholastic partnered with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to launch Primary Sources, with views from 20,000 teachers about the CCSS. “We found that teachers are supportive intellectually, conceptually. Where we have anxiety is around what it really looks like, what it means when the tests come down,” Mayer says.

Some wonder if publishers’ eagerness to align material to the CCSS could be compromising standards. “There are publishers in a rush to say everything is Common Core, which in some cases means putting a Common Core label on a product that was created before the standards existed,” says Duke, noting that a book she wrote pre-CCSS was recently labeled as CCSS-relevant. However, she acknowledges that materials don’t have to be new to be teachable.

Regarding publishing oversight, Diskey says, “There has been talk over the past three or four years about having a national advisory group that would review or vet publishers’ materials. Nothing has gotten off the ground.” The reason? “At a time when there is significant backlash, it might be politically difficult to get something like that up and running.”

Core Success: Student Motivation, Teacher Collaboration

Analyzing from the student perspective, Duke says, “The standards ask that the students read much more complex texts and do complex things with these texts. For students to meet them, they need to be much more motivated.” To help students become self-driven, teachers will have to learn motivational tools.

In Williamson’s view, teacher collaboration is the key. “The new standards have placed a premium on effective collaboration across content areas,” he says. “The more that educators are involved and working together on the ongoing planning and assessment of literacy learning, the more optimistic they are that standards will have a positive impact.”

COMMON CORE STANDARDS SHAKE UP THE EDUCATION BUSINESS

Hechinger Report – 10/15/2013

New York State has become the epicenter of a major transformation in the $7 billion textbook industry that threatens the preeminence of publishing behemoths like Pearson. A few large companies have monopolized the business for decades, although lately, districts have begun to move away from printed textbooks. Now, the new Common Core State Standards in math and English are  accelerating the trend as schools overhaul curricula to meet tougher academic guidelines.

accelerating the trend as schools overhaul curricula to meet tougher academic guidelines.

Small nonprofits, education technology startups, and companies that have never dabbled in producing educational content are stepping up to create learning apps and even full curricula that schools can use in addition to—or in place of—their old textbooks. “If I owned stock in a big publishing firm, I would sell it because I don’t have faith in their nimbleness,” said Patrick Murphy a political scientist at the University of San Francisco and co-author of 2 2012 report estimating how much it could cost states to implement Common Core.

New York has been the most prominent state to toss aside the old business model of relying on textbooks printed by the publishing giants. When it sought proposals for companies to create a statewide curriculum that matched the new standards, a key requirement was that any bidder had to offer the materials free online.

The large publishing companies, including Pearson and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, balked. Pearson spokesperson Kate Miller says the London-based company has been moving rapidly to create digital products, which she said last year were responsible for more than 50 percent of the company’s revenues. “We don’t even want to be called a textbook company anymore,” she said. (The company’s North American education revenues were $2.6 billion in 2012).

Under the Common Core State Standards, students will be asked to spend more time learning certain math concepts and will skip others. The idea is to give them a stronger foundation for algebra.

But giving away materials online meant losing potentially lucrative funding streams from selling materials to other states and districts. And the big publishers would have required more money, says Peter Cohen, president of McGraw-Hill Education K-12, based in New York City. At least $80 million for an elementary reading curriculum, for instance, not the less than $8 million New York paid.

But giving away materials online meant losing potentially lucrative funding streams from selling materials to other states and districts. And the big publishers would have required more money, says Peter Cohen, president of McGraw-Hill Education K-12, based in New York City. At least $80 million for an elementary reading curriculum, for instance, not the less than $8 million New York paid.

“What they got is not what we deliver,” Cohen said.

So instead, in 2012 the contracts went to a group of four smaller organizations, including three nonprofits.

“This is an open educational resource, so it’s a new breed of publisher,” said Scott Hartl, president and CEO of New York City-based Expeditionary Learning, which, prior to its curriculum contract with New York, focused mainly on running a growing network of schools in New York and other states.

The organization won a contract for $1.7 million from New York State to develop an English curriculum for grades three through five. A for-profit Boston-based company, Public Consulting Group (PCG), which provides schools with data services and advice on how to turn around struggling schools, won a $7.3 million New York contract to write an English curriculum for high school. (The company hired Expeditionary Learning to write the curriculum for grades six through eight.)

Core Knowledge, a Virginia-based nonprofit, won $5.1 million from the state to create an English curriculum for pre-kindergarten through second grade. And Common Core in Washington, D.C., another nonprofit, whose name pre-dates the creation of the new standards, is writing the math curriculum for all the grades for $8 million.

Core Knowledge, a Virginia-based nonprofit, won $5.1 million from the state to create an English curriculum for pre-kindergarten through second grade. And Common Core in Washington, D.C., another nonprofit, whose name pre-dates the creation of the new standards, is writing the math curriculum for all the grades for $8 million.

The money came from a federal grant New York won in the Obama administration’s “Race to the Top” competition. Materials have been produced in fits and starts, with some of the units finished by last spring and others still to come later in the year.

In New York, districts aren’t required to adopt the state-sponsored materials. In New York City, for example, the Department of Education has recommended two different curriculum options in middle school English, the Expeditionary Learning curriculum and one produced by Scholastic, a large for-profit company.

The new models are supposed to provide cost savings for schools and districts since they rely heavily on open educational resources which are found-online articles and materials that are downloadable from the Internet instead of pricier textbooks. But adopting the state curricula won’t be free, as districts and schools are already finding. Schools still will have to buy sets of novels and math materials, such as individual dry-erase boards for students.

The new models are supposed to provide cost savings for schools and districts since they rely heavily on open educational resources which are found-online articles and materials that are downloadable from the Internet instead of pricier textbooks. But adopting the state curricula won’t be free, as districts and schools are already finding. Schools still will have to buy sets of novels and math materials, such as individual dry-erase boards for students.

And teachers must also learn the new curriculum, which can take time and money. Although dollars spent on professional development can be hard to calculate, school districts have had to find hours over the summer or during the school year to train teachers, and in some cases pay them for the extra time or pay substitutes to replace them in class. The cost of sending educators to conferences or hiring outside trainers can also be steep.

As they roll out the new materials, the organizations have been selling their training services to schools (although under their contracts, they’ve offered a series of free in-person trainings to New York State teachers).

“This was a lever into the professional development market,” said Cheryl Dobbertin, Expeditionary Learning’s professional development director.

“This was a lever into the professional development market,” said Cheryl Dobbertin, Expeditionary Learning’s professional development director.

New York schools aren’t the only ones that will make use of the materials the organizations have created. Expeditionary Learning, for example, has been hired by Teach for America, the KIPP charter school network, and the state of Delaware to train teachers. The groups and state officials say other states have also expressed interest in using New York’s curricula, meaning big publishers may find fewer buyers for their new Common Core products.

But major education companies say they’re adjusting to the new business environment. “I think it’s a mixed bag in terms of what it’s going to mean from a business point of view,” said Margery Mayer, president of Scholastic Education. “But I think it’s looking better, honestly.”

She said districts are still purchasing Scholastic’s nonfiction books for school libraries and guided readers for small-group lessons, for example. And Mary Cullinane, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s executive vice president of corporate affairs, said the Boston-based company was seeing “steady adoptions and purchases across the country” of its new Common Core products.

Testing will also likely remain a significant revenue source for the big companies under Common Core. CTB/McGraw-Hill has won multiple contracts to help develop questions for Common Core tests. In 2011, Pearson won a $32 million contract to develop New York’s standardized tests, a contract that runs through 2015.

tests. In 2011, Pearson won a $32 million contract to develop New York’s standardized tests, a contract that runs through 2015.

“I’m not overly concerned about this,” said Cohen. “[You would be] hard pressed to find a school district that doesn’t have a McGraw-Hill program of some kind.”

Even so, education observers believe the new business models popping up to respond to the Common Core standards represent a turning point in the industry.

An important incentive driving the nonprofits to become curriculum publishers was not the money, but the chance to spread their ideas about education reform to more schools. Expeditionary Learning is a strong proponent of project-based learning, for example. And Core Knowledge promotes a back-to-the-classics philosophy of education based on the writings of its founder, E.D. Hirsch Jr.

“They’re just really focused on having that idea spread. I know that they loved the idea of having the program online for free,” said Lisa Hansel, a spokeswoman for Core Knowledge. “They were planning on putting it online for free anyway.”

WHAT APPLE IS WADING INTO: A SNAPSHOT OF THE K-12 TEXTBOOK BUSINESS

by Laura Hazard Owen – January 21, 2012

The battle for the college digital textbook market — including startups like Inkling and Kno — gets a fair amount of attention. But the K-12 textbook business that Apple now seeks to revolutionize is much less talked about outside of education circles.

Apple announced this week that it is partnering with the three largest K-12 educational publishers to sell iPad textbooks. It will be entering an $8 billion industry where most of the funds are controlled by state governments and school districts, which can mean long and politically charged funding discussions. Unlike in the college market, startups in the K-12 market have struggled to gain venture capital. One reason, on top of the bureaucracy that companies have to deal with: the digital infrastructure in many K-12 schools is weak, with an average of three students for every device as well as more mundane problems like too few electrical outlets.

controlled by state governments and school districts, which can mean long and politically charged funding discussions. Unlike in the college market, startups in the K-12 market have struggled to gain venture capital. One reason, on top of the bureaucracy that companies have to deal with: the digital infrastructure in many K-12 schools is weak, with an average of three students for every device as well as more mundane problems like too few electrical outlets.

That said there’s clearly some real opportunity: While many assume the K-12 market is largely controlled by the three big companies that Apple is partnering with, in fact, more than half of that $8 billion market isn’t. Here’s a look at some of the challenges and opportunities awaiting Apple.

How big is the K-12 education market?

The market is estimated at $8 billion. There are 50 million K-12 students in public schools in the U.S.

The market is estimated at $8 billion. There are 50 million K-12 students in public schools in the U.S.

K-12 school publishing — including elementary and high school textbooks and other teaching materials — is the second-largest publishing category in the U.S. after trade. Net sales revenue was $5.5 billion in 2010, according to the Association of American Publishers. (K-12 publishing net sales revenue fell 12.4 percent between 2008 and 2009 but increased by 7.1 percent between 2009 and 2010. Overall, net sales revenue between 2008 and 2010 declined by 6.2 percent.)

How is the K-12 publishing market different from trade and higher-ed publishing?

The main difference is that state governments and school districts procure about 90 percent of the books. “It’s very much unlike the consumer market where we decide to go into Barnes & Noble (NYSE: BKS) and buy a book,” says Jay Diskey, executive director of the AAP’s school division. “A school district will decide it needs a new reading program for its elementary school students and will request proposals from publishers. If the state likes the proposal, the contract is negotiated.”

where we decide to go into Barnes & Noble (NYSE: BKS) and buy a book,” says Jay Diskey, executive director of the AAP’s school division. “A school district will decide it needs a new reading program for its elementary school students and will request proposals from publishers. If the state likes the proposal, the contract is negotiated.”

Publishers don’t always sell the books individually; a parent may not be able to buy a single textbook, for instance. The AAP notes the average net unit price of a K-12 title was $65 in 2010, but extensive pricing data is difficult to obtain because so many books are bought in bulk by state governments and school districts.

Textbook rental doesn’t yet factor into K-12 education the way it does in higher ed, although some private and parochial schools are trying it.

Who are the main textbook publishers?

The K-12 textbook market is often seen as being dominated by just a few big companies, but that’s not entirely accurate, says Diskey. It’s true that three companies–McGraw-Hill (NYSE: MHP),  Pearson (NYSE: PSO) and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, the same three companies that are partnering with Apple in its new digital textbook store — capture about 85 percent of the K-12 core textbook market, which is worth roughly $3.2 billion. (The rest of that core market is made up of books from niche publishers on subjects like foreign languages, art and music, and books for technical and vocational schools.)

Pearson (NYSE: PSO) and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, the same three companies that are partnering with Apple in its new digital textbook store — capture about 85 percent of the K-12 core textbook market, which is worth roughly $3.2 billion. (The rest of that core market is made up of books from niche publishers on subjects like foreign languages, art and music, and books for technical and vocational schools.)

With the whole market estimated at $8 billion, though, there is still about $5 billion up for grabs outside of core textbooks. That portion includes many players, publishers and technology companies. They publish supplemental materials like workbooks, encyclopedias, books for teachers and reference works, all in print and digital formats. “There is far more diversity in the market than I think a lot of people understand,” Diskey says.

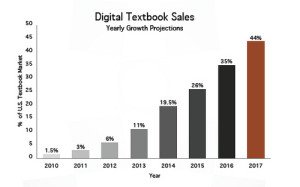

What is the role of digital?

Digital products are becoming a more important part of the K-12 school publishing market. Revenues from digital products increased by 45.6 percent between 2008 and 2010 to $638.7 million, according to the AAP (The market for print books is still much larger but revenues from print products declined 13.7 percent between 2008 and 2010, to $2.6 billion.)

Spending on e-learning as a percentage of overall K-12 education expenditure is small, according to the September 2011 White House report “Unleashing the Potential of Educational Technology” — it makes up just $0.46 of every $100 spent, for a total of $2.9 billion. (Expenditure on e-learning in higher education is over ten times greater: $5.60 per $100 spent for a total of $24.4 billion.)

makes up just $0.46 of every $100 spent, for a total of $2.9 billion. (Expenditure on e-learning in higher education is over ten times greater: $5.60 per $100 spent for a total of $24.4 billion.)

K-12 publishers all offer digital products now, but school districts have to decide how to buy them. The digital products are often bundled with print, but “a lot depends on the digital infrastructure in the school district and whether it can support digital learning,” says Diskey. “Not too many states have one-to-one student-to-hardware ratios. In order to have full-blown digital learning, students should have access to their own devices in the same way you had access to your own textbooks when you were in school.”

In fact, the national average ratio of students to hardware devices is three-to-one (three students for every computer, tablet, etc.) “That makes  learning very difficult,” Diskey says — and is another way K-12 is different from higher ed. About 90 percent of students arrive at college with at least one electronic device like a laptop, netbook or tablet. “By and large, K-12 students do not arrive with these devices,” Diskey says. This raises questions about who will pay for the devices — family or school districts.

learning very difficult,” Diskey says — and is another way K-12 is different from higher ed. About 90 percent of students arrive at college with at least one electronic device like a laptop, netbook or tablet. “By and large, K-12 students do not arrive with these devices,” Diskey says. This raises questions about who will pay for the devices — family or school districts.

School districts must deal with more mundane issues as well, such as whether there are enough electrical outlets to charge devices. “Behind all this, there’s the backdrop of schools providing textbooks,” Diskey says. In many states, schools are required to fund textbooks, but those mandates don’t always extend to digital materials. It will take “massive funding” to provide the 50 million K-12 public school students with hardware.

How will digital adoption change in the next year or so?

“I think you’ll see more partnerships between publishers and hardware producers such as Apple and others,” says Diskey. “For a long time at the K-12 level, content providers and hardware developers have operated in different silos, but they need to be partnered. (The announcement by Apple) is very good for publishers — new software tools and applications being developed means that more publishers, particularly smaller ones, can get into the digital market at the K-12 level. But there’s still a hang-up at the school level with funding and availability of devices.”

level, content providers and hardware developers have operated in different silos, but they need to be partnered. (The announcement by Apple) is very good for publishers — new software tools and applications being developed means that more publishers, particularly smaller ones, can get into the digital market at the K-12 level. But there’s still a hang-up at the school level with funding and availability of devices.”

What will encourage more entrepreneurship in the area?

The White House report reiterates the challenges of selling new products into the market:

An important feature of the market for K-12 educational technology products is the large number of institutional purchasers, each with its own distinct curriculum and procurement process. The school district is the relevant decision unit for most institutional purchases. Selling an educational product to a school district may require substantial contact with a diverse set of actors, including state and local procurement officers who oversee funding streams, academic consultants who advise districts, key school board members, and principals and teachers in individual schools. Moreover, decisions about purchases often involve an extended timeline.

Those barriers help explain why very little venture capital is spent on K-12 education: “In the last five years, estimates suggest that venture capital has totaled perhaps $200 million annually for education companies, backing an average of 25 new businesses per year. This venture capital investment compares to $4.4 billion for biotechnology, $3.0 billion for medical devices, and $4.8 billion for software.”

In a paper on K-12 entrepreneurship, Larry Berger and David Stevenson, the founders of K-12 tech product company Wireless Generation, describe some of the “relatively simple steps that districts, policymakers, foundations and entrepreneurs themselves could take to work around the barriers or dismantle them entirely.” They suggest that school districts and states could form consortia “in which they pool their resources and their expertise to help bring a new product or service to market.”

Berger and Stevenson also say states should commission more research and development instead of requiring a finished product. “When NASA wants a new spacecraft, it does not expect Boeing and Lockheed to build it on their own dimes in the hope of getting the contract,” they note. “It invites the industry to submit proposals and sometimes even funds the early development of competing designs — and then it picks a team with which it will work closely to bring a new product into existence.”

Finally, Berger and Stevenson note, “Entrepreneurship is often driven by the search for, and discovery of, ‘disruptive’ technologies and business models that transform a sector. It is not easy to figure out how the education sector should welcome disruptions and innovations that do not exist yet, but a simple first step would be to ask for them — to articulate the demands that would inspire entrepreneurs to try to create a supply.”

Sources: The Association of American Publishers, interviews and statistics; National Center for Education Statistics; “K-12 Entrepreneurship: Slow Entry, Distant Exit” by Larry Berger and David Stevenson; “Unleashing the Potential of Educational Technology,” Executive Office of the President Council of Economic Advisers, September 2011

Recent Comments