K-12 Teaching & Learning Platforms

OVERVIEW

The Common Core Curriculum Standards were devised to “provide a consistent, clear understanding of what students are expected to learn, so teachers and parents know what they need to do to help them.” Additionally, “The standards are to be designed to be robust and relevant to the real world, reflecting the knowledge and skills that our young people will need for success in college and careers, which will place American students in a position in which they can compete in a global economy.”

This educational reform and restructuring make information literacy skills a necessity as students seek to construct their own knowledge and create their own understandings. Today instruction methods have changed drastically from the mostly one-directional teacher-student model, to a more collaborative approach where the students themselves feel empowered. (see: Common Core Initiative).

This section takes a look at the various delivery platforms that are being devised to bridge the new Common Core educational materials and the assessment of student proficiency in those curriculums. The Common Core does not dictate any one teaching/learning platform for the delivery of what will be the Common Core aligned K-12 curriculum. This choice is left up to the teacher as each teacher has difference experience, teaching style and insights to what works.

Educators are selecting various platforms of resource-based learning (authentic learning, problem-based learning and work-based learning) to help students focus on the process and to help students learn from the content. Information literacy skills are necessary components of each. Within a school setting, it is very important that a students’ specific needs as well as the situational context be kept in mind when selecting topics for integrated information literacy skills instruction. The primary goal should be to provide frequent opportunities for students to learn and practice information problem solving. (see: K-12 Education Restructuring)

BEST PRACTICES

The term “Best Practice” is used as a blank term for all of the various Learning/Teaching Platforms being used in K-12 education. The concept was first developed in college instruction and has been used to describe “what works” in a particular situation or environment. When data support the success of a practice, it is referred to as a “research-based practice or scientifically based practice.” However, a particular practice that has worked for someone within a given set of variables may or may not yield the same results across educational environments.

Evidence-based education has been defined as “the integration of professional wisdom with the best available empirical evidence in making decisions about how to deliver instruction.” Professional wisdom allows educators and family members to adapt to specific circumstances or environments in an area in which research evidence may be absent or incomplete. But without at least some empirical evidence, education cannot resolve competing approaches, generate cumulative knowledge, and avoid fads and personal biases (see: SERC).

Some of the more common attributes of a “Best-Practices’ Teaching & Learning Platforms:

A Clear and Common Focus hat all students can learn and improve their performance

High Standards and Expectations means that all students are engaged in rigorous course of study in which the high standards of performance are clear and consistent and the conditions for learning are modified and differentiated

Strong Leadership creates a common culture of high expectations based on the use of skills and knowledge to improve the performance of all students

Supportive, Personalized, and Relevant Learning provide positive personalized relationships for all students while engaging them in rigorous and relevant learning

Parent/Community Involvement means that the school community works together to actively solve problems and mentoring and outreach programs provide for two-way learning between students and community/business members

Monitoring, Accountability, and Assessment are continually adjusted on the basis of data collected through a variety of reliable methods that indicate student progress and needs

Curriculum and Instruction are aligned through rigorous, research-based teaching and learning strategies and students are actively involved in their learning through inquiry, in-depth learning, and performance assessments

Professional Development means appropriate instructional support and resources are provided to implement approaches and techniques that are learned through teacher training

Time and Structure are flexible to accommodate the varied lives of students, staff, and community in order to improve student performance in programs that extend beyond the traditional school day, year and beyond the school building

COMMON CORE FOCUS

In an effort to remediate our international K-12 test score rankings, an independent organization examined shortcomings and strengths in our system. The result was the Common Core State Standards (CCSS), intended to raise rigor, embed real-world relevance into our curriculum, and keep students on the same academic page regardless of their home state. The anchor standards explicitly instruct students to research, assess sources, and avoid plagiarism.

The CCSS authors correctly assessed this generation’s needs and supported a student-centered inquiry-based research model rather than a teacher-defined task. Now, those research endeavors would be rigorous, arguable, open-ended, and worthy of debate. Those debates are aligned with the Common Core.

The following is a list of some of the Common Core Learning/Teaching objectives:

- Students need to be prepared to compete in a global economy

- Instruction needs to reflect the knowledge and skills necessary for success in college and careers

- Instruction needs to contain clear understanding of what students are expected to learn

- Real-world relevance needs to be embedded into K-12 curriculum

- Curriculum needs to be designed to be robust and relevant to the real world

- Curriculum needs to develop integrated information literacy skills in students

- Curriculum needs to be written so students can draw knowledge from the text

- Curricula should provide opportunities for students to build knowledge through close reading of a text

- All curriculum needs to raise rigor

- The assessment of the realigned standards should be both challenging and rigorous

- Students need to master deeper levels of critical thinking and comparative text analysis

- Students need to construct their own knowledge and create their own understandings

- Students need to research, assess sources, and avoid plagiarism

- Students need to focus on the process and learn from the content

- High-quality questions should be included in all curriculums

- Such questions should encourage students to “read like a detective”

- Questions should be written so they can only be answered through close attention to the text

- Students should be assigned tasks that are text dependent

- Text should prompt relevant and central inquiries into the meaning of source material

- Students should uncover and discover rather than merely cover material

- Students need to communicate and demonstrate their ability to comprehend the details of what is explicitly stated in the text

- Student background knowledge and experiences can illuminate the reading but should not replace attention to the text itself

- Students need to make valid inferences that logically follow from what is stated in the text

- Students need to use evidence to back up their written responses

- In math, students have to learn more than one way to solve the same problem, and they must explain their methods

- Students need to be kept on the same academic page regardless of their home state

TEACHER FACILITATION

Core Success: Student Motivation, Teacher Collaboration

All over the world, teachers are learning to repackage their curriculum so that students uncover and discover, rather than merely cover material. The Common Core Initiative Standards goes on to state that the assessment of the realigned standards should be both challenging and rigorous. Today instruction methods have changed drastically.

There is a real potential to promote a deeper engagement with the subject matter and enhance the student experience by creating opportunities for group learning but this does require the teacher  to focus more on the design and development of the learning experience and less on transmission of content. However, many students will want to be given the solutions to problems rather than taking responsibility for finding information and discussing it together and so there is a need for induction and teacher training and support.

to focus more on the design and development of the learning experience and less on transmission of content. However, many students will want to be given the solutions to problems rather than taking responsibility for finding information and discussing it together and so there is a need for induction and teacher training and support.

The realization of this type of the collaborative-based learning environment depends to a large extent on the skill of the teacher to lead and facilitate group discussion but many teachers find this task difficult to perform satisfactorily and too readily fall back in frustration on their reserve position of expert and prime talker.

Since the standards ask the student to read much more complex texts and do complex things with these texts for students to meet them, they need to be much more motivated. To help students become self-driven, teachers will have to learn motivational tools.

Teacher collaboration is the key. The new standards have placed a premium on effective collaboration across content areas. The more that educators are involved and working together on the ongoing planning and assessment of literacy learning, the more optimistic they are that standards will have a positive impact.

THE CHALLENGE OF DELIVERY

The Common Core requires the realigned curriculum to elicit more of a pro-active response from students. The program wants the development of societal “soft skills” as students matriculate such  the six Cs of critical thinking, collaboration, communication, cooperation, creativity and curiosity. From the K-12 curriculum developers and teachers has come a creative and progressive response to this challenge.

the six Cs of critical thinking, collaboration, communication, cooperation, creativity and curiosity. From the K-12 curriculum developers and teachers has come a creative and progressive response to this challenge.

Learning-by-doing is generally considered the most effective way to learn. The Internet and a variety of emerging communication, visualization, and simulation technologies now make it possible to offer students challenging and authentic learning experiences ranging from experimentation to real-world problem solving. Whether it’s call problem-based, project-based or inquiry-based the process falls under the larger framework of Authentic-based Learning.

Many of the following Learning/Teaching Platforms overlap but for the most part they are uniquely identifiable. From this the so called “Based” learning programs have emerged including:

- Collaborative-based Learning

- Problem-based Learning

- Project-based Learning

- Blended-based Learning

- Case-based Learning

- Computer-based Learning

- Inquiry-based Learning

- Innovation-based Learning

- Competency-based Learning

- Entertainment Engagement-based Learning

- Performance-based Learning

- Work-based learning

COLLABORATIVE-BASED LEARNING

(The following on collaborative-based learning is an abstract from: “Collaborative project-based learning and problem-based learning in higher education: a consideration of tutor and student roles in learner-focused strategies” by Roisin Donnelly and Marian Fitzmaurice, Learning and Teaching Centre, Dublin Institute of Technology)

Overview

The theory behind Collaborative or Group Learning is that students have knowledge, views and experiences to share that have value. Collaboration empowers students with a proactive in-class community focus are precursor to adult life. Self-confidence is built around critical thinking, articulation of viewpoints, collaboration-based problem solving and the awareness of new knowledge. Group discussion allows students to attend more clearly to meaning as they interact with the language of the subject and put into their own words the issues arising from a particular topic.

community focus are precursor to adult life. Self-confidence is built around critical thinking, articulation of viewpoints, collaboration-based problem solving and the awareness of new knowledge. Group discussion allows students to attend more clearly to meaning as they interact with the language of the subject and put into their own words the issues arising from a particular topic.

Since students must be supported to develop subject knowledge in a group learning context students develop key skills such as communication and teamwork. Students can only become proficient in a subject or skill by practicing it and in a group learning context the students learn how to work within a group and listen and n egotiate with others in order to resolve dilemmas or conflicts. Although collaborative learning is most commonly related to Problem-based Learning and Project-based Learning, the methodology can be found in most of the “based” learning platforms.

Problem-based learning and project-based learning share several characteristics. Both are instructional strategies that are intended to engage students in authentic, “real world” tasks to enhance learning. Students are given open-ended projects or problems with more than one approach or answer, intended to simulate real life situations. Both learning approaches are defined as student-centered, and include the teacher in the role of facilitator or coach. Students engaged in project- or problem-based learning generally work in cooperative groups for extended periods of time, and are encouraged to seek out multiple sources of information. Often these approaches include an emphasis on authentic, performance-based assessment.

Despite these many similarities, project- and problem-based learning are not identical approaches. Project-based learning tends to be associated with engineering and science instruction. Problem-based learning is also used in these disciplines, but has its origins in math practices.

Despite these many similarities, project- and problem-based learning are not identical approaches. Project-based learning tends to be associated with engineering and science instruction. Problem-based learning is also used in these disciplines, but has its origins in math practices.

The line between project- and problem-based learning is frequently blurred and that the two are used in combination and play complementary roles. Fundamentally, problem- and project-based learning have the same orientation: both are authentic, constructivist approaches to learning.

The difference between the two approaches lies in the variations. With project-based learning the end product is the organizing center of the project which can be elaborate and shape the production process requiring extensive planning and effort. The end product drives the planning, production, and evaluation process and culminates with a presentation of the end product. With problem-based learning the end products are simpler and more summative, such as a group’s report on their research findings and where the inquiry and research (rather than the end product) is the primary focus of the learning process.

Another difference between the two approaches is the extent to which a problem is the organizing center of the project. With project-based learning projects it is assumed that any number of problems will arise and students will require problem-solving skills to overcome them. With problem-based learning projects begin with a clearly stated problem or problems and require a set of conclusions or a solution in direct response, where the problematic situation is the organizing center for the curriculum.

Arguably, induction to both strategies is very important for both students and staff. Student induction must have a group work session, and include more support for those without group work experience. Through a series of team-building and problem-solving group activities, students need to become exposed to the problem-based and project-based way of thinking in an enjoyable way.

Problem-based Learning

Problem-based learning is both a curriculum and a process. The curriculum consists of carefully selected and designed problems that demand from the learner acquisition of critical knowledge,  problem solving proficiency, self-directed learning strategies, and team participation skills. The process replicates the commonly used systemic approach to resolving problems or meeting challenges that are encountered in real life.

problem solving proficiency, self-directed learning strategies, and team participation skills. The process replicates the commonly used systemic approach to resolving problems or meeting challenges that are encountered in real life.

Problem-based learning, as the name implies, begins with a problem for students to solve or learn more about. Often these problems are framed in a scenario or case study format. Problems are designed to be “ill-structured” and to imitate the complexity of real life cases. As with project-based learning, problem-based learning assignments vary widely in scope and sophistication. The approach uses an inquiry model: students are presented with a problem and they begin by organizing any previous knowledge on the subject, posing any additional questions, and identifying areas they need more information.

The primary goal should be to provide frequent opportunities for students to learn, practice information problem solving and facilitate repetition of information seeking actions and behavior.

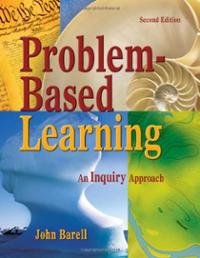

Role of the Teacher in PBL

As the amount of direct instruction is reduced in problem based learning, students assume greater responsibility for their own learning. The teacher’s role becomes one of subject matter expert, resource guide, and facilitator of learning in the group. This arrangement promotes group processing of information rather than an imparting of information by the instructor. The teacher’s role is to encourage student participation, provide appropriate information to keep students on track, avoid negative feedback, and assume the role of fellow learner. In essence, teachers should be more concerned with the process of learning of students than with the content of their learning. To do this properly requires many skills from the instructor, most of them in the field of social-pedagogy.

concerned with the process of learning of students than with the content of their learning. To do this properly requires many skills from the instructor, most of them in the field of social-pedagogy.

Fundamentally, the teacher is an educator who leads a task-oriented group to successfully achieve the outcomes of a learning program. In doing this, the teacher has to fulfil several responsibilities and is accountable to the teaching program for the satisfactory completion of them. These responsibilities require abilities and skills relevant to the principles and practice of problem-based learning, group dynamics, the assessment of student learning, the use of learning resources and managerial skills.

The role of the instructor is very different from the usual teacher’s role. Rather than being a “content expert” who provides the facts, the teacher is a facilitator, responsible for guiding students to identify the key issues in each problem and to find ways to learn those areas in appropriate breadth and depth. Teachers in a problem based learning curriculum need to alter their traditional teaching methods of lectures, discussions, and asking students to memorize materials for tests. As such, teachers focus their attention on questioning student logic and beliefs, providing hints to correct erroneous student reasoning, providing resources for student research, and keeping students on task. Because this role will be new to some teachers, they may have concern moving away from their past practice.

Studies of teacher roles and behaviors have found that subject matter expertise of teachers enhanced both student learning and the learning process. With respect to teacher behaviors, subject matter experts were able to employ more effective process facilitative behaviors such as asking stimulating questions, offering counter examples or seeking clarification, and that these behaviors were related to written test score achievement. To be effective, teachers must possess both facilitatory teaching skills and content expertise, with content expertise a pre-condition to effectively perform the behaviors.

Although students have much more responsibility in PBL than in most conventional approaches to teaching, the teacher is not just a passive observer. He or she must be active and directive about the learning process to assure that the group stays on target and makes reasonable choices on what issues are important to study. Teachers also have considerable influence on what is learned by selecting the problems in the first place, and by creating teacher guides and specific outcomes for each phase of the curriculum.

Role of Students in PBL

As problem-based learning is a student-centered process, it is the responsibility of the individual student to participate fully, not only for his or her own learning, but also to aid the learning of others in the group. Although a significant proportion of time is spent alone in the library or at the computer, the full benefits of PBL cannot be realized in isolation.

In PBL, students devise a plan for gathering more information, then do the necessary research and reconvene to share and summarize their new knowledge in the group. Students may present their conclusions, and there may or may not be an end product. Again, students ideally have adequate time for reflection and self-evaluation. All problem-based learning approaches rely on a problem as their driving forces, but may focus on the solution to varying degrees. Some problem-based approaches intend for students to clearly define the problem, develop hypotheses, gather information, and arrive at clearly stated solutions. Others design the problems as learning-embedded cases which may have no solution but are meant to engage students in learning and information gathering.

An unanticipated issue with problem based learning is the traditional assumptions of the student. Most students have spent their previous years assuming their teacher was the main disseminator of knowledge. Due to this orientation towards the subject-matter expertise of their instructor and the traditional memorization of facts required of students, many students appear to have lost the ability to “simply wonder about something.” This is especially seen in first year students who often express difficulties with self-directed learning.

Although students generally prefer problem based learning courses, and their ability to solve real-life problems appears to increase over traditional instruction, there are issues to be aware of in moving towards this type of learning. Contributing to this divergence is the time requirement placed upon academic staff to assess student learning, prepare course materials, and allow students to complete the reduction in coverage of course material.

Students all seek approval from their teachers. They need guidance and role models that they can respect and trust. It is essential for teachers to be honest with students. Even though effective teacher avoid the ‘expert’ role, they can have a powerful impact on students.

Induction Process

Considering problem-based learning, before students go into the curriculum proper, a PBL orientation is essential to prepare students for PBL and enables them to make full use of the PBL process for life-long learning. Such an orientation can cover the following:

- Knowing and using PBL;

- Guest speakers from graduates on their views of PBL;

- Guest speakers from clients/employers on their views of the type of employees that they are looking for and their experience with students who learnt via PBL approach;

- Coping with change;

- PBL Small Group Learning Process;

- Assessment for PBL;

Within the orientation, a specific focus on teamwork is vital, in particular, it can include problem-challenging and self-esteem games alongside how effective feedback in group situations is going to be constructed and conveyed.

Academic Achievement

Few academics doubt the ability of students prepared in problem based learning to exhibit strong reasoning and team building skills. Concern has been raised, however, over the breadth of content covered. As the focus of problem based learning centers on a specific problem, academic achievement scores often favor traditional teaching methods when standardized tests are used, but favor neither method when non-standardized forms of assessment are employed. These measures include problem-solving ability, interpersonal skills, peer-tutor relationships, the ability to reason, and self-motivated learning. In contrast, traditional instruction is judged better in the coverage of science content areas and in evaluating students’ knowledge content. Although problem based learning tends to reduce initial levels of learning, it can improve long-term retention.

Resources

A continuing challenge for CPBL and PBL groups is “How much detail is enough?” Students should be encouraged to bring books and previous class notes and use them in the learning, if necessary, to clarify concepts and terminology. To obtain additional information, the teacher may direct students to a specific resource (journal article, book, expert, website etc.). It is important for students to avoid wasting time tracking down an obscure reference. However, on the other hand, it is important for them to develop skill in finding good information and taking responsibility for the self-evaluation and development of personal study skills.

to clarify concepts and terminology. To obtain additional information, the teacher may direct students to a specific resource (journal article, book, expert, website etc.). It is important for students to avoid wasting time tracking down an obscure reference. However, on the other hand, it is important for them to develop skill in finding good information and taking responsibility for the self-evaluation and development of personal study skills.

Generally, there is not a specific list of references developed for each problem considered. Part of the overall learning experience implicit in CPBL and PBL is the development of skills that will facilitate access to learning resources throughout students’ future higher education and professional career.

Teachers should encourage students to discuss matters of interest pertaining to specific problems with their peers and with more senior students. Similarly, by virtue of the multi-disciplinary nature of many of the learning issues that will evolve from individual problems, it is important to guide them towards discussions of the subject at hand.

In CPBL and PBL, resources need to be allocated to take specific factors into account. More generous teaching support needs to be allocated than is provided for “traditional” courses. Additional instruction time needed to assess a final project report and for double marking of that report needs also to be included.

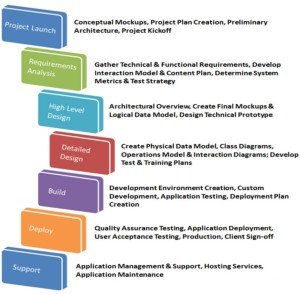

Project-based Learning

Project-Based Learning is an individual or group activity that goes on over a period of time, resulting in a product, presentation, or performance. It typically has a time line and milestones, and other aspects of formative evaluation as the project proceeds.

In Project-based Learning the end product requires effort and shapes the planning, production and evaluation process. With Project-based Learning it is implicitly assumed that any number of problems will arise and students will require problem-solving skills to overcome them.

Project-based learning typically begins with an end product in mind, the production of which requires specific content knowledge or skills and typically raises one or more problems which students must solve together. Projects vary widely in scope and time frame, and end products vary widely in levels of technology use.

The collaborative project-based learning approach uses a production model: first, students define the purpose for creating the end product and identify their intended audience. They research their topic, design their product, and create a plan for project management. Students then begin the project, resolve problems and issues that arise in production, and finish their product.

Students may use or present the product they have created, and ideally reflect on and evaluate their own work. The entire process is meant to be authentic, mirroring real world production activities and utilizing students’ own ideas and approaches to accomplish the tasks at hand. Though the end product is the driving force in collaborative project-based learning, it is the content knowledge and skills acquired during the production process that are important to the success of the approach.

Collaborative project-based learning adopts a multi-disciplinary approach to bringing together knowledge and skills. Designing the appropriate course materials provide the flexibility for a move away from transmission teaching to a more student-centered learning and teaching environment. The term learning environment can be used to distinguish it from approaches based primarily on a sequence of questions, answers and feedback. A learning environment places greater emphasis on problem solving situations and mechanisms to assist the learner in their tasks and monitor learning.

Role of the Teacher in Project-based Learning

Collaborative project-based work is well established as a component of many courses in Arts, Social Sciences, Science, and Technology in higher education. The argument for the strategy principally rests upon the assumption that it is a means of developing a more active and motivated student-centered approach to learning.

rests upon the assumption that it is a means of developing a more active and motivated student-centered approach to learning.

A reason for introducing this form of learner-focus strategy is that students may have relatively little understanding of the real world examples that lecturers use in illustrating concepts.

In conventional face-to-face teaching, the introduction of project-based methods entails recognizing that there will be less teaching control over the learning processes that students must accept more responsibility for organizing their own learning experience, and that assessment is more complex because the piece of work that results from each student project will be unique.

This variety is usually accommodated within the “conventional” learning framework by laying greater emphasis on providing opportunities for teacher supervision and guidance at appropriate stages during the course of the project. In a traditional setting of face-to-face teaching means that adjusting the balance of supervision and guidance is a relatively flexible process. Knowledge of the project, built up by the teacher/student contact, can make assessment of it easier. This kind of environment is created through a variety of teaching and learning activities directed by teachers, learners and peers because each of these serves different purposes. Knowledge is constructed through learner activity and interaction.

This variety is usually accommodated within the “conventional” learning framework by laying greater emphasis on providing opportunities for teacher supervision and guidance at appropriate stages during the course of the project. In a traditional setting of face-to-face teaching means that adjusting the balance of supervision and guidance is a relatively flexible process. Knowledge of the project, built up by the teacher/student contact, can make assessment of it easier. This kind of environment is created through a variety of teaching and learning activities directed by teachers, learners and peers because each of these serves different purposes. Knowledge is constructed through learner activity and interaction.

Collaborative project work often goes on for a considerable length of time, though the time span may range from a single afternoon a full school term. Advantages of project-based learning include the encouragement of student initiative, self-directiveness, inventiveness, and independence. However, a project-based course demands from students a heightened level of self-confidence, motivation, and ability to organize their own work plans. A number of the issues are also present for the teacher including project related time allocation, project scope delineation, and teacher responsibilities.

There may be extra involvement and time commitment that collaborative project-based work entails for teachers such as extra workloads on the resources and on the more complex task of project assessment.

The Teacher’s role at the design stage

Strong guidance is needed on how to initiate work at the outset of the project in order to limit student attempts to undertake overly ambitious projects;

Project specifications should be more detailed than they would be in “face-to-face” teaching;

Careful piloting and testing of proposed projects should be undertaken in advance of the first course presentation in order to establish reasonable estimates of time required for successful student completion;

Sample projects should be provided to show students the scope of project in order to help students form a realistic picture of what they are expected to achieve;

Course teams should be aware of the importance of a Project Guide (a document containing guidelines for undertaking the relevant project) and strive to make it as clear and as helpful as possible;

It should be recognized that extra demands will be made on teachers both in terms of personal involvement and of time commitment in evaluating and assessing projects. Collaborative project-based methods also imply more teacher involvement in terms of reassurance and guidance.

Assessment will also be more demanding, and more resources may need for assessment than would be required on “teacher-directed” courses. Teachers also need guidance on the extent to which they should allow students to follow an independent path and at which point they should intervene if a student’s chosen direction seems to be going badly off-course. The flexibility of tutorial contact makes it easier to remedy the problem of students taking a “wrong” direction.

From an academic point of view, teachers also need to be clear about the rewards and penalties that students may incur by pursuing an unconventional solution to their project problem. They need to know the balance that the course aims to achieve between encouraging students to produce unique solutions and rewarding a successful arrival at the “end goal.”

Role of the Student in Project-based Learning

Project-based Learning is a student centered learning strategy which is intended to develop student skills as an independent learner and project execution facilitate this. A project takes the student beyond what they already know about a topic and therefore requires research from a variety of sources including books, research papers and the World Wide Web. What students include in their projects and how they present them will vary according to student discipline and the specific purpose of the project. However doing a collaborative project will require students to put into practice a range of important skills such as searching literature, collecting information from a wide variety of sources, analyzing data and working as part of team. In addition skills of communication and time management will be important.

beyond what they already know about a topic and therefore requires research from a variety of sources including books, research papers and the World Wide Web. What students include in their projects and how they present them will vary according to student discipline and the specific purpose of the project. However doing a collaborative project will require students to put into practice a range of important skills such as searching literature, collecting information from a wide variety of sources, analyzing data and working as part of team. In addition skills of communication and time management will be important.

Managing the Project

Doing a collaborative project requires that the student identifies key learning issues and take responsibility for their own learning as they undertake an extended piece of work and time management is a key area. Project commencement is advised as soon as possible and the students should plan their time to ensure that steady progress is made and regular team meetings are held.

A project brief can be daunting but it can help greatly if the task is broken down into a series of stages and then the group can logically work through each stage until each student’s task is completed.

Project Stages

- Planning

- Researching

- First Draft

- Rewriting

- Submitting the project

Stage 1 – Planning

At this stage it is essential to make sure that the students understand what the project requires. The brief should be carefully read several times and initial thoughts and any questions should be written down. At this stage it is important that the project brief be discussed amongst the students. If any student is unsure it is very important that he/she meet with the teacher to avoid completing a task only to realize the student misunderstood it. Once the students have clarified the project brief they are now ready to begin researching.

Stage 2 – Researching

This stage involves the group deciding on areas of responsibility for each individual. Then it will be necessary to locate relevant literature taking into account student aims and purposes, so that the information gathered is relevant. The amount of research will depend on the nature and length of the project and the time available to complete the work.

A large amount of information is available electronically and the students will need to be able to use the library catalogues, databases and internet search engines. It is best to start with a visit to the library and librarians will give advice and guidance. It is very easy at this point to branch off in a variety of directions and spend a lot of time researching literature that is not directly relevant. In order to avoid this possibility it is good practice for the students to keep in front of them the project title which will support them to search through the literature using key words and thereby locate relevant material. Having located the literature it is important that the students take notes and record the main ideas gleamed from the text and think about how these relate to what they already know. It will be necessary to think critically and form conclusions based on a systematic evaluation of the available evidence.

Also the students should take care to record reference sources correctly as failure to do this will mean that at a later stage they may have to revisit all the literature consulted in order to check references and this can be very time consuming. It is expected in academic work that sources are correctly referenced and always avoid plagiarism, which is presenting somebody’s work as their own without acknowledging it.

Stage 3 – First Draft

Having located and evaluated the relevant information the students can now move logically to the next stage, which is to write a first draft of their section of the project. All good writers produce a draft, which they revise and edit to produce a final version. Once they begin to write they will find that they will begin to clarify their thinking. The students should try to get all their ideas down on paper first and they can reorganize later to ensure that there is logic to the draft and that their writing is clear and coherent and meets academic expectations. The students must be very careful to reference the work of other people so as there is no plagiarism in the finished work. In producing a collaborative project, there will be a need to decide as a group how best to synthesize the individual elements into a coherent whole. A number of approaches can be taken to do this but it will be essential that the final document is logical and consistent.

There is a common formula for writing an assignment that may appear simplistic but does provide a good structure for a project:

- Introduction: Provide the reader with a clear outline of what the students are going to do in the project and relate it to the project title.

- Main Body: Draw on relevant material and present student arguments in a structured way.

- Conclusion: Bring everything together so that there is a sense of completion. This involves summarizing the main points, making recommendations and highlighting issues for further investigation.

Stage 4 – Rewriting

It is important to understand that all writing involves rewriting and that even the most gifted writers will revisit work and edit and revise. Pay attention to the following as you make annotations and amendments:

- he document clearly adheres to the project brief

- The objectives are achieved and there are no gaps in the work

- There is a logical flow to the document

- Formal academic language is used

- The conclusions are clear to the reader

- The document is clear and well-presented and adheres to the conventions laid down in the assignment brief

Conclusion

It could be argued that the skill of the twenty first century graduate will be to articulate the right questions and to understand where and how they can search for knowledge, not remember the  answers ( see: “How to Get a Job at Google” below). It is importance for instructors to adopt teaching strategies which cultivate and develop in students the processes of thinking, learning how to learn, problem solving and team-working, within a context of self-directed learning. Well-designed collaborative project-based and problem-based learning strategies have the potential to support the development of academic knowledge and skills and combine these in a way that enhances the student learning experience.

answers ( see: “How to Get a Job at Google” below). It is importance for instructors to adopt teaching strategies which cultivate and develop in students the processes of thinking, learning how to learn, problem solving and team-working, within a context of self-directed learning. Well-designed collaborative project-based and problem-based learning strategies have the potential to support the development of academic knowledge and skills and combine these in a way that enhances the student learning experience.

Problem-based learning places the students in control of their own learning. Instructor lecturing has been the main stay of education for, well, forever. This has been because it has been proven to be effective in transmitting information. However, if we wish to develop thinking skills, problem solving abilities and lifelong learning skills a more student-centered approach is necessary.

The Buck Institute for Education’s Project-based Learning program, which augments traditional curriculum with student projects that are designed to resemble work-place problem solving, is another example of project-based learning.

The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation has given the National Association of State Boards of Education (NASBE) a three-year grant of approximately $774,000 to help state boards to encourage exploration of deeper learning. The NASBE is embarking on an effort to go beyond policies that expand the breadth of learning to develop student expertise in critical thinking, problem solving, effective communication, collaboration, and self-awareness (see the following article “NASBE Initiative Delves into Deeper Learning”).

BLENDED-BASED LEARNING

The Blended-based Learning model refers to any progressive teaching/learning methodology which combines traditional K-12 teaching methods with innovative programs to encourage the development of the so called “soft skills” of critical thinking, creativity, communication, collaboration, cooperation and curiosity.

Lecturing is without doubt effective for transmitting information but if we wish to develop thinking skills, problem solving abilities and lifelong learning skills a more student-centered approach must be taken. This involves a change in the role of the lecturer from presenting information to students in a mostly one-directional teacher-student model to a more collaborative approach where the students themselves feel empowered which facilitates and guides learning.

With the “Flip Teaching” model Flip teaching (or flipped classroom) is a form of “Blended-based Learning” which encompasses any use of technology to leverage the learning in a classroom, so a teacher can spend more time interacting with students instead of lecturing. This is most commonly being done using teacher-created video lectures that students view outside of class time. It is also known as “the backwards classroom,” reverse instruction,” flipping the classroom,” and “reverse teaching.”

The Friday Institute for Educational Innovation, which part of the North Carolina State University College of Education, FIZZ project has student video tape their lesson and present them to their peers thus creating the potential of the group to learn from each other. This creates “ownership” in the presenting student which is the highest form of cognitive recognition. This also gives students an opportunity to direct and take responsibility for their own learning (see: Blended-based eLearning).

CASE-BASED LEARNING

Case-based Learning is a teaching platform that is most often used with older students and graduate students that are working in their field of study. In this platform students reflect on their own experiences and use the experiences of other students. The goal is to clarify the connection between theory and practical application to encourage problem solving in the real world.

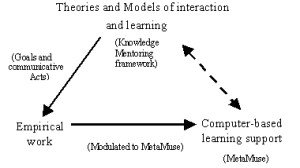

COMPUTER-BASED LEARNING

Blogs, wikis, and Google Docs are commonly used CSCL mediums within the teaching community. The ability to share information in an environment that is becoming easier for the lay person has  caused a major increase of use in the classroom. One of the main reasons for its usage states that it is “a breeding ground for creative and engaging educational endeavors.”

caused a major increase of use in the classroom. One of the main reasons for its usage states that it is “a breeding ground for creative and engaging educational endeavors.”

Using Web 2.0 social tools in the classroom allows for students and teachers to work collaboratively, discuss ideas, and promote information. Blogs, wikis, and social networking skills are significantly useful in the classroom. After initial instruction on using the tools, students also reported an increase in knowledge and comfort level for using Web 2.0 tools. These collaborative tools additionally prepare students with technology skills necessary in today’s workforce. (see: Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning).

INQUIRY-BASED LEARNING

Inquiry-based Learning is an activity in which the student extracts meaning from experience. It is essentially a description of human activity as an approach to teaching and learning.

When viewed from a curricular perspective it is a process that provides students opportunities to engage in life beyond the classroom using the tools and methods of scientists, artists, and problem  solvers, to gain a deeper understanding of themselves and the world around them. This process is personal, action-based, social, and reflective. It has a critical process that questions received knowledge and social structures, and even its own processes. It therefor invites a continual questioning of what it means to teach and learn, what counts as knowledge, and what meaning or action follows from learning.

solvers, to gain a deeper understanding of themselves and the world around them. This process is personal, action-based, social, and reflective. It has a critical process that questions received knowledge and social structures, and even its own processes. It therefor invites a continual questioning of what it means to teach and learn, what counts as knowledge, and what meaning or action follows from learning.

An old adage states: “Tell me and I forget, show me and I remember, involve me and I understand.” The last part of this statement is the essence of inquiry-based learning. Inquiry implies involvement that leads to understanding. Furthermore, involvement in learning implies possessing skills and attitudes that permit the student to seek resolutions to questions and issues while they construct new knowledge.

“Inquiry” is defined as “a seeking for truth, information, or knowledge — seeking information by questioning.” Individuals carry on the process of inquiry from the time they are born until they die. This is true even though they might not reflect upon the process. Infants begin to make sense of the world by inquiring. From birth, babies observe faces that come near, they grasp objects, they put things in their mouths, and they turn toward voices. The process of inquiring begins with gathering information and data through applying the human senses — seeing, hearing, touching, tasting, and smelling. Thirteen.org

Inquiry-based learning covers a range of approaches to learning and teaching, including:

- Field-work

- Case studies

- Investigations

- Individual and group projects

- Research projects

Specific learning processes that people engage in during inquiry-learning include:

- Creating questions of their own

- Obtaining supporting evidence to answer the question(s)

- Explaining the evidence collected

- Connecting the explanation to the knowledge obtained from the investigative process

- Creating an argument and justification for the explanation

More recently, Heather Banchi and Randy Bell suggest that there are four levels of inquiry-based learning in science education:

- confirmation inquiry

- structured inquiry

- guided inquiry and

- open inquiry

In confirmation inquiry, people are provided with the question and procedure (method) where the results are known in advance, and confirmation of the results is the object of the inquiry. Confirmation inquiry is useful to reinforce a previously learned idea; to experience investigation processes; or to practice a specific inquiry skill, such as collecting and recording data.

In structured inquiry, people are provided with the question and procedure (method), however the task is to generate an explanation that is supported by the evidence collected in the procedure.

In guided inquiry, people are provided with only the research question, and the task is to design the procedure (method) and to test the question and the resulting explanations. Because this kind of inquiry is more open than a confirmation or structured inquiry, it is most successful when people have had numerous opportunities to learn and practice different ways to plan experiments and record data.

In open inquiry, people form questions, design procedures for carrying out an inquiry, and communicate their results. Wikipedia

INNOVATION-BASED LEARNING

Because it is often said that innovation is comprised of 90 percent failure and 10 percent success a progressive form of assessment has emerged. Innovation is the fluid structure between failure and recovery. Innovation-based Learning is predicated on the positive side of failure. Because of the more rigorous K-12 curriculum and testing, test scores are predicted to drop by as much as 30% in states that lowered their assessment standards. This is not necessarily a bad thing as several positive results will happen. First, the student will be rigorously challenged by the test and the student will experience failure. The first is an expectation of the Common Core Initiative and the second is a common complaint by employers of students entering the work force. (See the following article “Finding Team Players In iPod Age”)

positive side of failure. Because of the more rigorous K-12 curriculum and testing, test scores are predicted to drop by as much as 30% in states that lowered their assessment standards. This is not necessarily a bad thing as several positive results will happen. First, the student will be rigorously challenged by the test and the student will experience failure. The first is an expectation of the Common Core Initiative and the second is a common complaint by employers of students entering the work force. (See the following article “Finding Team Players In iPod Age”)

The way the program works is that students are allowed to take a course test three times. After the first two tests the teacher goes over the answers of the tests in a manner that creates learning and understanding similar to how Blender-based Learning works. The student can accept the score of any of the tree tests. Since the test questions will come out of a “test pool” even if the student gets 100 percent on a test they can retake the test with new questions to see how they do. However, if they get a lower score the highest score counts.

Student proficiency will improve over time if they are afforded regular opportunities to learn, re-apply the skills they have learned and do not fear the assessment method.

COMPETENCY-BASED LEARNING

In Competency-based Learning students are graded and receive credit the “mastery of material” rather than the certain number of hours completed in the classroom. Students earn credit for skills learned through internships, community service, independent study, performing arts groups and on-line courses. This platform is also known as Extended Opportunity-based Learning or EOLs.

ENTERTAINMENT ENGAGEMENT-BASED LEARNING

Educational entertainment engagement is nothing new. For millenniums teachers have been using various forms of entertainment to educate their students. The earliest recorded form of education is the morality play. The early Greeks used the morality play to convey the societal concepts of right and wrong and operas such as Mozart’s “The Magic Flute” and “Don Giovanni” depict damnation for lapses in morality. (See Motivational Entertainment-based eLearning)

play. The early Greeks used the morality play to convey the societal concepts of right and wrong and operas such as Mozart’s “The Magic Flute” and “Don Giovanni” depict damnation for lapses in morality. (See Motivational Entertainment-based eLearning)

The most commonly used form of education entertainment engagement is the educational video game. Other forms of entertainment engagement include music, lyrics (poems), dance (movement) episodic elements (serials), dramatic enactments (scene plays) and graphic novels (comic books). Each educational entertainment element is used for the various student learning styles (see Blended-based Learning) including spatial, kinesthetic and musical learning. The following is a list of common educational entertainment elements:

- Educational Computer Games and Puzzles

- Animations

- Graphic Novels (comic books)

- Episodics

- Dramatic Curriculum Enactments

- Music

- Lyrics

- Poetry

- Dance

Entertainment education can be used to reach those students who are disenfranchising from tradition learning methods. More and more curriculum is being developed with entertainment elements such as Scholastic’s “You Wouldn’t Want to…” history series which uses humor and graphic (cartoon) drawings and makes the reader one of the characters in the historical event.

Crabtree Publishing has developed a series of math books called “Stone Age Geometry.” This innovative series supports STEM fields identifies six key geometric concepts and puts them in a prehistoric world. Historic and technological real-word applications of lines, spheres, circles, triangles, squares and cubes are presented by fun characters in a humorous context.

Crabtree Publishing has developed a series of math books called “Stone Age Geometry.” This innovative series supports STEM fields identifies six key geometric concepts and puts them in a prehistoric world. Historic and technological real-word applications of lines, spheres, circles, triangles, squares and cubes are presented by fun characters in a humorous context.

Analog board games are also gaining traction as teachers and librarians can modify them to meet instructional goals. The flexibility of board games often trumps the more ridged format of digital games. Christopher Harris and Brian Mayer, who wrote “Libraries Got game: Aligned Learning Through Modern Board Games (ALA Editions, 2010), contend that game designers, like authors, often perform in-depth research into their games which produce a fun and instructional tool. Games like this satisfy the Common Core’s call for new types of resources strong in detail and worthy of deep study. Two of the board games they have developed are “His Freedom: The Underground Railroad” and “1960: The Making of the President.”

which produce a fun and instructional tool. Games like this satisfy the Common Core’s call for new types of resources strong in detail and worthy of deep study. Two of the board games they have developed are “His Freedom: The Underground Railroad” and “1960: The Making of the President.”

Entertainment-based Learning is in its infancy but has a bright future in not only helping disinterested students to embrace learning but also help successful students relieve the stress caused by everyday student life.

PERFORMANCE-BASED LEARNING

(The following is from an Israeli foreign language school – the exact identity could not be ascertained)

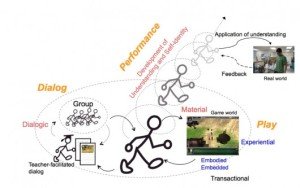

The performance-based approach to education, which is not unlike both Project-based and Problem-based Learning models (see above), enables pupils to use their knowledge and apply skills in realistic situations. It differs from the traditional approach to education in that as well as striving for mastery of knowledge and skills, it also measures these in the context of practical tasks.  Furthermore, performance-based education focuses on the process students go through while engaged in a task as well as the end product, enabling them to solve problems and make decisions throughout the learning process.

Furthermore, performance-based education focuses on the process students go through while engaged in a task as well as the end product, enabling them to solve problems and make decisions throughout the learning process.

In addition, performance-based education stimulates the development of other important dimensions of learning, namely the affective, social and metacognitive aspects of learning.

Regarding the affective (emotional) aspect of learning, performance-based education motivates students to participate in interesting and meaningful tasks. It helps pupils develop a sense of pride in their work. Encouraging students to experiment with their increasing control of the subject knowledge alleviates anxiety over “making a mistake.”

The social aspect of learning is reflected in the peer interaction that performance-based tasks require. Students thus develop helpful social skills for life. Such cooperative work leads to peer guidance and other kinds of social interaction such as negotiating, reaching a consensus, respecting others’ opinions, individual contribution to the group effort and shared responsibility for task completion.

As for the metacognitive aspect of learning (student thinking about their own learning), skills such as reflection and self-assessment also contribute to the learning process. When teachers require students to think about what they are learning, how they learn and how well they are progressing, they develop skills which make them more independent and critical-thinkers.

What is Performance-Based Assessment?

The following is a comprehensive definition of performance assessment:

“Performance assessment is thedirect, systematic observation of an actual pupil performance … and rating of that performance according to pre-established performance criteria. Students are asked to perform a complex task or create a product. They are assessed on both the process and end result of their work. Many performance assessments include real-life tasks that call for higher-order thinking.”

“Performance assessment is thedirect, systematic observation of an actual pupil performance … and rating of that performance according to pre-established performance criteria. Students are asked to perform a complex task or create a product. They are assessed on both the process and end result of their work. Many performance assessments include real-life tasks that call for higher-order thinking.”

(The North Central Regional Educational Laboratory 2001)

Performance-based assessment thus enables pupils to demonstrate specific skills and competencies by performing or producing something. It can help teachers assess both what pupils can do (specific benchmarks) and what they have achieved within a specific teaching program based on the Curriculum standards. Besides focusing on the quality of the final product of a student’s work, performance-based assessment also rates the student’s learning process. Assessing both product and process provides an accurate profile of a student’s subject ability. Teachers can track students’ work on a task, show them the value of their work processes and help them self-monitor so that they can use tools such as periodic reflections, working files and learning logs more effectively.

What is a Performance Task?

A performance task enables students to demonstrate their ability to integrate and use knowledge, skills and work habits in a meaningful activity. These tasks show how a pupil uses language in a real-life situation, rather than just providing information on pupils’ theoretical knowledge.

The following are some examples of performance tasks, divided into products and performances:

| PRODUCTS | PERFORMANCES |

| books (fables, cook books, stories, flip-flop books, accordion books, scrolled books, big books, cartoons, autobiographies, biographies) | song contest, poetry contest, joke contest |

| wall display (story train, collage, poster, ad, bulletin board, exhibition) | game show |

| computer game, board game, card game | radio broadcast |

| advertising campaign | multimedia presentation |

| survey | poster presentation |

| poem/rap/advertising jingle | dramatic performance |

| letter, petition, postcard | show-and-tell presentation |

| album (alphabet, family, zoo, holiday) | speech |

| rules or instructions | video clip (news, weather, interview) |

| pamphlet (e.g., road safety rules for parents) | demonstration (cookery, craft) |

| 3-D model | debate |

| newspaper/ newsletter/articleplan or diagram | storytelling |

The following characteristics should be remembered when designing a performance task:

- It has various outcomes; it does not require one right answer.

- It is integrative, combining different skills.

- It encourages problem-solving and critical thinking skills.

- It encourages divergent thinking.

- It focuses on both product and process.

- It promotes independent learning, involving planning, revising and summation.

- It builds on pupils’ prior experience.

- It can include opportunities for peer interaction and collaborative learning.

- It enables self-assessment and reflection.

- It is interesting, challenging, meaningful and authentic.

- It requires time to complete.

(Adapted from Birnbaum, 1997)

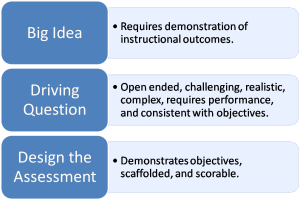

How to Design and Assess a Performance Task

The process of designing performance tasks can be divided into three simple steps.

Step 1. List the specific skills and knowledge you wish pupils to demonstrate.

Teachers should identify the goals (i.e., types of knowledge and skills) students are expected to reach in each teaching unit. This step is quite simple, since the knowledge and skills a student needs are the Curriculum’s standards and benchmarks in the various domains. Once this list is compiled, the teaching goals to be assessed through performance tasks (as opposed to other assessment tools) should be selected.

Step 2. Design a performance task that requires students to demonstrate these skills and this knowledge.

Teachers should set tasks that will demonstrate which knowledge and skills have been developed. The students’ performance on these tasks should illustrate what they have learned and the degree to which they have achieved the teaching goals. Performance tasks should be motivating, challenging and appropriate to students’ level and cognitive ability. Foundation level tasks will be simple and structured, and as pupils become more proficient and independent, the tasks will become more complex and less structured. As mentioned above, the tasks should be related to real-life experiences. See the list of performance task types above.

Step 3. Develop explicit performance criteria and expected performance levels measuring students’ mastery of skills and knowledge (rubrics).

Determine criteria for successful task mastery. The Curriculum specifies criteria relevant to each domain. See: Assessment Rubrics to further clarify this point.

WORK-BASED LEARNING

(The following is from Utah State Office of Education)

Work-Based Learning (WBL) gives students the opportunity to learn a variety of skills by expanding the walls of classroom learning to include the community. By narrowing the gap between theory and practice, work-based Learning creates meaning for students.

WBL provides opportunities for students to learn a variety of skills through rigorous academic preparation with hands-on career development experiences. Under the guidance of adult mentors, students learn to work in teams, solve problems, and meet employers’ expectations.

Work-Based Learning Goals and Benefits

Through Work-Based Learning, students have the opportunity to see how classroom instruction connects to the world of work and future career opportunities. WBL provides the following:

- Active participation of educators, employees, labor, students, parents, and appropriate agency and community representatives

- Development of learning and workplace competencies

- Motivation to stay in school

- Improvement of student grades

- Improvement in student employability

- Increased awareness of nontraditional career opportunities

- Help for students in identifying Career Pathways

Career and Technical Education (CTE) Pathways

Work-Based Learning supports the CTE Pathways initiative and WBL experiences are available in each CTE Pathway. Through a variety of WBL experiences students see, firsthand, how classroom instruction connects to the world of work and future career opportunities. Experiences include, but are not limited to, apprenticeships, career fairs, field studies, guest speakers, job shadows and student internships.

Our vision is to see that all students have the opportunity to learn skills and to be introduced to the working world through a variety of Work-Based Learning activities which will enable them to be prepared to enter the workforce upon graduation from high school.

Program Delivery Components

Work-Based Learning is integrated and grade-appropriate at all levels of education. Career awareness, exploration, orientation, and preparation activities are coordinated with School-Based Learning activities.

- Awareness: In grades K-6, students are introduced to a multitude of careers through career days (such as tool days and vehicle days), workplace visits, job shadowing, and guest speakers.

- Exploration: In grades 7-8, students explore career options in a particular field of work through career fairs, field studies, job shadowing, and guest speakers.

- Orientation: In grades 9-10, students become familiar with a specific career(s) through career fairs, job shadowing, and guest speakers.

- Preparation: In grades 11-12, students prepare for a career of their choosing through internships, apprenticeships, and clinical work experiences.

Work-Based Learning Benefits Students by:

- Exposing students to adult role models

- Improving scholastic student motivation

- Applying classroom learning

- Exploring career options

- Helping students make better decisions and plans

- Improving post-secondary prospects

- Helping students understand workplace expectations.

- Exposing students to state-of-the-art practices and technology

Work-Based Learning Activities

- Apprenticeships

- Career Fairs

- Field Studies

- Guest Speakers

- Job Shadows

- Student Internships

Course Offerings

- CTE Introduction

- Career Apprenticeship Starts Here

- Critical Workplace Skills

- Related Work-Based Learning

Program Results/Funding

Since the 1990s, an interest in using the community effectively in the classroom has grown. The Utah State Legislature recognizes the value Work-Based Learning experiences have in a student’s education and has allocated ongoing funding for this program.

Recent Comments