Common Core Initiative

COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS INITIATIVE

In the 1990s the “Accountability Movement” began in the U.S. as states started being held to mandatory tests of student achievement, which were expected to demonstrate a common core of knowledge that all citizens should have to be successful. As part of this overarching education reform movement, the nation’s governors and corporate leaders founded Achieve in 1996 as a bi-partisan organization to raise academic standards, graduation requirements, improve assessments, and strengthen accountability in all 50 states. The initial motivation for the development of the Common Core State Standards was part of the “American Diploma Project” (ADP).

A report titled, “Ready or Not: Creating a High School Diploma That Counts,” from 2004 found that both employers and colleges are demanding more of high school graduates than in the past. According to Achieve, Inc., “current high-school exit expectations fall well short of [employer and college] demands.” The report explains that the major problem currently facing the American school system is that high school graduates were not provided with the skills and knowledge they needed to succeed. “While students and their parents may still believe that the diploma reflects adequate preparation for the intellectual demands of adult life, in reality it falls far short of this common-sense goal.” The report continues that the diploma itself lost its value because graduates could not compete successfully beyond high school, and that the solution to this problem is a common set of rigorous standards.

The “No Child Left Behind” was an attempt to address America’s shortfall in student achievement. Unfortunately, the NCLB programs fell far short of achieving the goal of advancing student competence. Because of teacher credibility being tied to student test scores tests were “dumb down” and teachers began to only “teach to the test.” Teacher survival and not student accomplishment became the order of the day.

In response to this report in 2009 the National Governors Association (NGA) convened a group of educators to work on developing curriculum standards in the area of mathematics and for literacy instruction. Announced on June 1, 2009, the initiative’s stated purpose is to “provide a consistent, clear understanding of what students are expected to learn, so teachers and parents know what they need to do to help them.” Additionally, “The standards are designed to be robust and relevant to the real world, reflecting the knowledge and skills that our young people need for success in college and careers,” which will place American students in a position in which they can compete in a global economy.

The standards are copyrighted by NGA Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) and the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO). The copywrite ensures that the standards will be the same throughout the nation. The standards also carry a generous public license which waives the copyright notice for State Departments of Education to use the standards; however, two conditions apply. First, the use of the standards must be “in support” of the standards and the waiver only applies if the state has adopted the standards “in whole.”

The standards are copyrighted by NGA Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) and the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO). The copywrite ensures that the standards will be the same throughout the nation. The standards also carry a generous public license which waives the copyright notice for State Departments of Education to use the standards; however, two conditions apply. First, the use of the standards must be “in support” of the standards and the waiver only applies if the state has adopted the standards “in whole.”

The Common Core, which has national implications, promises a new approach to curriculum that focuses on critical and creative thinking as opposed to a bubble-test driven curriculum. Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) and Smarter Balance Assessment Consortium (SBAC) are the federally funded national testing consortia that are creating the Common Core tests due out in the 2014-2015 school year. PARCC, with a grant of $185m, had 21 member states while SBAC, with a grant of $175m, had 24 states.

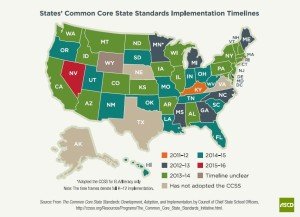

Forty-five of the fifty states in the United States were original members of the Common Core State Standards Initiative, with the states of Texas, Virginia, Alaska, and Nebraska not adopting the initiative at a state level. Minnesota has adopted the English Language Arts Standards but not the Mathematics Standards. Since then Alabama, Utah, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania and Georgia have dropped out and it will take only three more states to withdraw from PARCC national Common Core tests to jeopardize the group’s federal grant. Oklahoma will remain a PARCC member state to retain their connection to its “knowledge base,” but not administer its tests.

High costs, technological unpreparedness, and parent and teacher concerns over the testing length are the major concerns prompting state drop out. Also nonparticipating states may believe their standards are higher than the Common Core or worry the federal government is becoming too involved in education since states have always done their own tests and have always had control at the local level. PARCC released a new cost estimate of $29.50 per student to administer just two tests, ELA and Mathematics, while Georgia spends $8-9 per student to administer a five-subject assessment.

standards are higher than the Common Core or worry the federal government is becoming too involved in education since states have always done their own tests and have always had control at the local level. PARCC released a new cost estimate of $29.50 per student to administer just two tests, ELA and Mathematics, while Georgia spends $8-9 per student to administer a five-subject assessment.

Technology and technology costs are also a major concern since the Common Core tests are required to be taken online from the first year. Oklahoma was one of five or more states to experience widespread computer crashes this spring (2013) as students attempted to test online. This invalidated thousands of test results. Only 28 percent of Oklahoma school districts have the infrastructure necessary for the new exams.

The limited nature of the high stakes tests based on the state standards has impacted the ability to develop the kind of engaging, immersive experience that fosters difficult-to-assess 21st century learning skills such as creativity, collaboration, and problem solving. The assessments that are now being developed for the CCSS are trying to address these shortcomings.

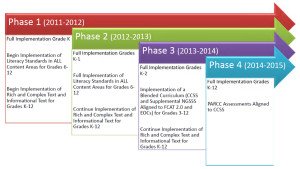

Common Core Implementation

The following is an abstract from “WHAT’S HAPPENING AT THE CORE?” By

Sarah Bayliss, School Library Journal -2/2014

Whether you love them, hate them, or are somewhere in between, the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) and their high bar for student learning are here, having now been adopted in 45 states and the District of Columbia.

With the rolling implementation of these rigorous standards and student tests, educators are still grappling to understand the CCSS, assemble materials, and adjust their teaching methods. Because the English Language Arts standards require students to master deeper levels of critical thinking and comparative text analysis, teachers must prepare students for more demanding standardized assessments. They also need to brace students for lower test scores, as has been the case and a point of controversy in pilot states.

State of the common core: too much, too fast?

The rigorous nature of the standards isn’t the issue, some believe. “There’s nothing wrong with the Common Core,” says Deborah Wooten, associate professor of reading in the Theory and Practice in Teacher Education Department at the University of Tennessee. “Implementation is the problem,” she adds. “This is all brand-new to the students, teachers, and administrators.”

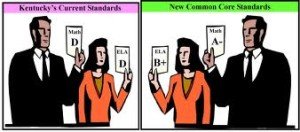

“What is the purpose of raising the bar so high that many more students fail?” educator Diane Ravitch criticizes on her blog, noting that, when Kentucky piloted the CCSS, measured student proficiency dropped by 30 percent. She writes, “We are a nation of guinea pigs, almost all trying an unknown program at the same time.”

“Slow down testing,” says Wooten. “Let [teachers] get a better footing in the Common Core” before implementing the new student tests. Responding to such pressures in New York State, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver made the case last month for delaying implementation.

For most educators, adapting to the CCSS is simply something they must do—and fast. “The teachers I’ve worked with were given staff development for the Common Core during the summer,” Wooten says, and “a few days to prepare their lesson plans.” However, she adds, “A lot of teachers are adjusting.”

In Tennessee and some other states, teachers are judged by their students’ scores on tests. Because “test scores are tied to teacher evaluation,” Wooten says, “the pressure is pretty intense. Test scores in the South are typically lower than anywhere else.”

Common Core Criticism

The Common Core has drawn criticism from across the political spectrum, from the Brookings Institute to the Libertarian Cato Institute, conservatives, including several Republican governors, have assailed the program as a federal “top-down” takeover of state and local education systems. South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley said her state should not “relinquish control of education to the federal government neither should we cede it to the consensus of other states.”

assailed the program as a federal “top-down” takeover of state and local education systems. South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley said her state should not “relinquish control of education to the federal government neither should we cede it to the consensus of other states.”

Policy analysts have also questioned the efficacy of the Common Core. The Heritage Foundation argues that the Common Core’s focus on national standards will do little to fix deeply ingrained problems and incentive structures within the education system. Similarly, the Brookings Institute issued research calling into question whether the standards would have a significant effect. According to the NGA one motivating factor for creating the Common  Core standards was the United States’ low ranking on international test results, but a study concluded there does not seem to be a relationship between the U.S.’s low score on these tests and its economic ranking. The nonprofit Fair Test argues that assessments developed to measure the Common Core standards will mean more, but not much better, tests in schools that are already suffering from too much testing and “Teaching to the Test.”

Core standards was the United States’ low ranking on international test results, but a study concluded there does not seem to be a relationship between the U.S.’s low score on these tests and its economic ranking. The nonprofit Fair Test argues that assessments developed to measure the Common Core standards will mean more, but not much better, tests in schools that are already suffering from too much testing and “Teaching to the Test.”

Education commentators have argued the program drains initiative from teachers and enforces a “one-size-fits-all” curriculum that ignores cultural differences among classrooms and students. Additionally, education experts, including a former president of the National Council of Teachers of English, have argued that the creation of Common Core standards lacked sufficient public input and was driven by corporate interests and policy-makers, rather than experienced educators.

Diane Ravitch, education historian, education policy analyst, researcher at New York University, and a previous U.S. Assistant Secretary of Education under presidents George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton, states in her 2013 book “Reign of Error” that the Common Core standards have never been field-tested and that no one knows whether they will improve education. Critics have said that the standards emphasize rote learning and uniformity over creativity, and fail to recognize differences in learning styles.

Additionally, education reform advocate Sandra Stotsky has argued that the standards will lead to students reading more nonfiction texts, rather than being exposed to challenging literature. Mark Naison of the Badass Teachers Association argues that the Common Core costs school districts a great deal of money and reduce resources for things that inspire children, such as art and music classes.

In Pennsylvania protests against the new standards prompted the state to replace the Common Core with a hybrid that includes much of the state’s current and less demanding standards. But teachers are still mired in uncertainty because the standards aren’t set in stone until they go through Pennsylvania’s regulatory review process. Opponents of the standards on the right are still fighting to halt them in the House and Senate education committees. So are Keystone exam opponents on the left, worried about imposing high stakes on students without adequate resources to prepare them.

In Pennsylvania protests against the new standards prompted the state to replace the Common Core with a hybrid that includes much of the state’s current and less demanding standards. But teachers are still mired in uncertainty because the standards aren’t set in stone until they go through Pennsylvania’s regulatory review process. Opponents of the standards on the right are still fighting to halt them in the House and Senate education committees. So are Keystone exam opponents on the left, worried about imposing high stakes on students without adequate resources to prepare them.

Common Core Support

Supporters point out that the standards were developed and adopted at the state level by the NGA and the CCSSO, and that feedback was solicited and incorporated throughout the process. In addition, former Republican governor, Jeb Bush, claims that Common Core is supported by the majority of Republican governors.

The Common Core standards only specify what students should know at each grade level and describe the skills that they must acquire in order to achieve college or career readiness. School districts are responsible for choosing curricula based on the standards.

An analysis of previous state standards by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute determined that the Common Core standards are “clearly superior” to those used in thirty-nine states in math and thirty-seven states in English. For thirty-three states, the Common Core is superior in both math and English.

Mathematicians Edward Frenkel and Hung-Hsi Wu argue that mathematical education in the U.S. is in “deep crisis” caused by the way math is currently taught in schools. Math textbooks, which are widely adopted across the states, create “mediocre de facto national standards” and alienate students from the subject. The Common Core standards address these issues and “level the playing field” for students. They also point out that the adoption of Core Standards and how best to test students are two separate issues.

In his article “Why Our Nation Needs Common Standards,” (Hechinger Report, July 18, 2013) Jonah Edelman said “The Common Core Standards—clear and high standards for what every child in the United States should know by the end of each grade—are a practical and effective solution for a system that now dooms some students to learn far less than their peers who happen to live in other states.

In his article “Why Our Nation Needs Common Standards,” (Hechinger Report, July 18, 2013) Jonah Edelman said “The Common Core Standards—clear and high standards for what every child in the United States should know by the end of each grade—are a practical and effective solution for a system that now dooms some students to learn far less than their peers who happen to live in other states.

They benefit students in states with weak academic standards. They benefit teachers who want to access and share the best possible lesson plans. They benefit parents who have a right to know that an “A” in school or a “proficient” on the state test actually means their child is on track.

They benefit military families who often move across state boundaries. They benefit colleges and employers, who for the first time will know that a high-school graduate from Arizona is as prepared as one from New York when it comes to the critical reading, critical reasoning, and foundational math skills necessary for college and career success. They benefit college-aged students, many of whom now take costly remedial classes (without earning college credit) because their previous schooling didn’t prepare them for higher education. And raising standards everywhere makes it more feasible for kids in poor areas to know they have a fighting chance.”

Kentucky was the first to implement the Common Core standards, and began offering the new curriculum in math and English in August of 2010. In 2013 Time magazine reported that the high school graduation rate had increased from 80% in 2010 to 86% in 2013, test scores went up 2 percentage points in the second year of using the Common Core test, and the percentage of students considered to be ready for college or a career, based on a battery of assessments, went up from 34% in 2010 to 54% in 2013.

Common Core Initiative Articles

Recent Comments